Chinese aid workers in bright red jumpsuits and helmets sifted through the rubble of homes and ancient Tibetan monasteries in freezing temperatures after the earthquake that occurred on January 7. Chinese state media described the rescue efforts as “fast and orderly” and framed them as a demonstration of “ethnic unity.”

Authorities quickly announced the final toll: 126 dead, 337 injured and more than 3,600 homes in ruins. However, amid the devastation, a different reality emerged, one that exposed the harsh controls imposed on Tibet, where the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) strictly manages information, even in the aftermath of a natural disaster.

Controlling the narrative

Two days after the earthquake, Global Times, a Chinese tabloid known for promoting CCP propaganda, published an extensive report on the aid response. This account never referred to the Himalayan nation as “Tibet” but instead used “Xizang,” a name the CCP introduced in 2023. Critics see this change as a deliberate attempt to erase the country from the map.

According to Global Times, rescue teams reached the epicenter within 30 minutes. The report claimed that, within days, affected residents had warm shelter and received three hot meals a day. It goes on to paint the picture of a unified response, where countless aid workers and volunteers provided relief without ethnic divisions. It declared, “While a natural disaster has torn a wound into the snowy plateau, the entire nation is working tirelessly to heal it,” calling the effort “the best interpretation of human rights.”

However, what this portrayal failed to mention was Tibet’s extreme restrictions. The Chinese government bans international media from entering the region, and Freedom House, a US-based advocacy group, ranks Tibet alongside North Korea as one of the most repressive places in the world. In Tibet, sharing politically sensitive information online or communicating with someone abroad without permission can result in lengthy prison sentences. In the days following the earthquake, Tibetans posting on Douyin (the Chinese version of TikTok) reported strict censorship. One user refused to discuss the disaster, citing a Tibetan proverb: “If one does not control the long tongue, one’s round head will be in trouble.”

With the Chinese government controlling all official information, Global Times and similar outlets had total dominance of the narrative. Yet, in the weeks since the earthquake, Tibetan rights organizations and refugees leaked information contradicting the official reports. These sources revealed that the CCP carefully managed details of aid distribution and even the reported death toll.

Despite Global Times’ claims of “ethnic unity,” Chinese authorities restricted Tibetans’ movements within 24 hours of the quake. The International Campaign for Tibet (ICT), a US-based advocacy group, documented new security checkpoints that limited access to the disaster zone, preventing Tibetans from delivering aid.

One day after the quake, officials in Dingri, where the epicenter lay, posted a notice suspending relief donated by Tibetans. ICT suggested that authorities wanted to maintain control over the official narrative. The notice stated: “At present, Dingri County has sufficient reserves of various disaster relief supplies. After having discussions, it has been decided to stop accepting donations of disaster relief supplies from all walks of life from now on.” The Tibetan government-in-exile, based in India, responded with an open letter urging the CCP to allow more aid to be distributed, especially medical assistance.

On dangerous ground

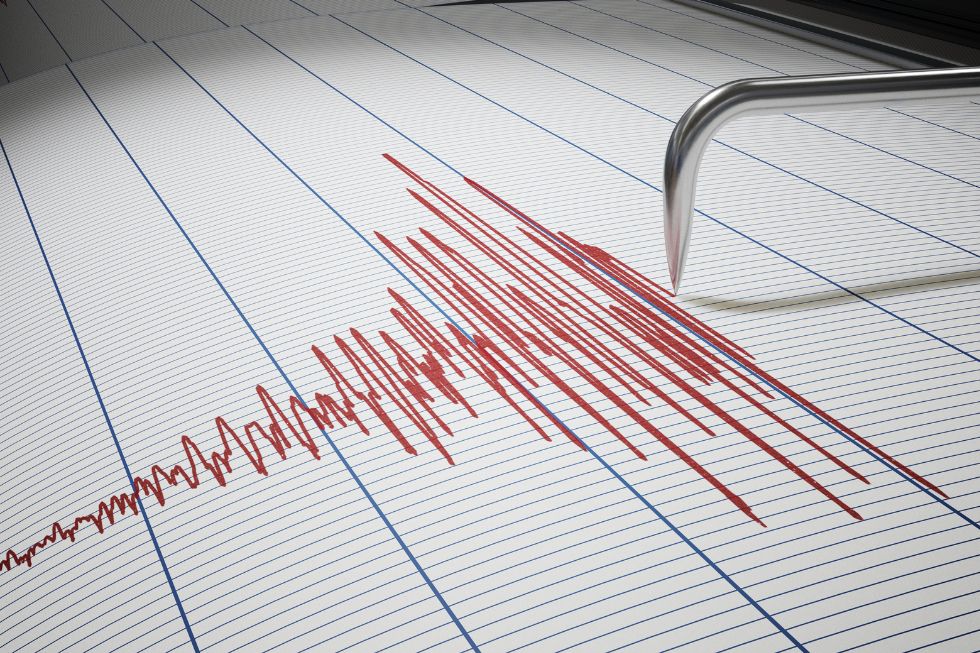

The Tibetan leadership also raised concerns about China’s regional development policies. The letter directly challenged Global Times’ claim that China had modernized Tibet, instead blaming “excessive” dam construction and mining for increased seismic activity. In 2008, a devastating earthquake in Tibet killed nearly 70,000 people. Experts later suggested that a massive Chinese-built dam may have triggered the disaster, making it the deadliest earthquake linked to human activity.

China’s hydropower projects have drawn criticism for their environmental and geopolitcal consequences. These dams disrupt major rivers flowing into India, Bangladesh and other parts of Southeast Asia. Concerns about their safety have persisted for years. In the days following the quake, Chinese officials initially claimed that none of their dams sustained damage. However, they later admitted that five of the 14 dams in the affected area had developed structural problems. One of them had suffered such severe damage that its walls tilted, forcing the evacuation of 1,500 people living downstream.

The CCP’s lack of transparency has also cast doubt on the official death toll. Authorities reported 126 deaths within 48 hours of the quake and never revised. The tremors were strong enough to be felt more than 200 miles away, yet ICT research showed that officials based their count on just 27 villages within a 12-mile radius of the epicenter. Radio Free Asia, a US-government-funded news outlet, questioned the death toll two days after its release. Reports from local Tibetans suggested that at least 100 had died in a single township. On January 11th, Radio Free Asia’s Tibetan Service cited morgue staff who estimated the actual death toll exceeded 400. Given Tibet’s severe repression and isolation, the true number of casualties may never be known.

The next recovery phase will focus on reconstruction, but many Tibetans fear that Beijing will seize control of the process without consulting local communities. ICT cited a government whistleblower who revealed that after a 2010 earthquake killed 3,000 people, officials diverted emergency funds for personal gain, depriving many survivors of housing assistance. “China had painted a picture of remarkable recovery,” ICT stated. “However, reality is far from what the Chinese government claims.” If history repeats itself, the victims of this disaster may find themselves abandoned, while officials exploit the tragedy to strengthen their grip over Tibet.

[Kaitlyn Diana edited this piece]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment