The electorates’ responses to the initiatives of the British prime minister and the French president have been severe. They demonstrate the principle of negative democracy that appears to be the dominant new trend in the West.

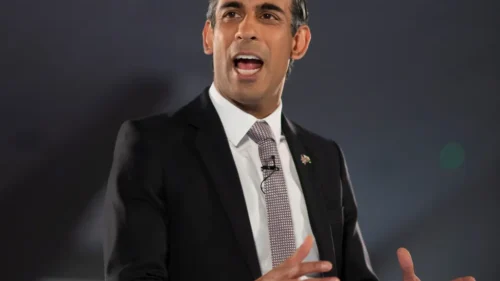

Rishi Sunak, the UK’s most recent Tory Prime Minister, understood that his party’s hold on power was weakening. So he thought he could catch his opponents off guard, forcing the electorate to cling to the idea of continuity in times of uncertainty. He provoked an unprecedented bloodbath that left the Tories with an abject minority in Parliament, and Labour with a crushing majority: 412 to 121!

Similarly, French President Emmanuel Macron had a panicked reaction to being handily distanced by Marine Le Pen’s far right National Rally in June’s European parliamentary elections. He called a snap election to take place exactly three weeks later, for the stated sake of “clarification.” The first round of that election confirmed the electorate’s massive rejection of Macron’s policies and even of the man himself.

The first round also allowed the electorate to “proclaim” its preference for the xenophobic right over “Macronisme.” The second round permitted voters to favor the left, leaving Macron stranded in a no man’s land: an undefined, powerless middle. Even though he has three years left to preside over the nation, Macron has become the lamest of lame ducks.

But the most obvious example of the negative democracy trend would be the last two United States presidential elections, along with the upcoming one. In 2016, pollsters revealed that both Hillary Clinton, who was nevertheless expected to win, and Donald Trump, the ultimate outsider, held the titles of the two most unpopular presidential candidates ever to face off in the modern era.

The 2020 election pitted the consistently unpopular Trump against an aging Democratic workhorse, Joe Biden, who was clearly past his prime. “Sleepy Joe” won the primaries not because he inspired voters, but because the party’s establishment, working in the background, pushed him through. Above all, they wished to avoid nominating the much more popular Democrat: Bernie Sanders. In Negative Democracy, popular candidates are viewed as potential threats to their parties.

Biden was never popular but he had two redeeming factors: his association with former US President Barack Obama and his appearance as a politician who could conduct “business as usual.” He contrasted with the mercurial, unpredictable Trump. Was he villainous? No one was sure. But a majority of voters saw him as the lesser of two evils.

2024 offers a rematch between the already rejected Trump and — as polls seem to indicate — the soon-to-be rejected Biden. Both are now widely perceived as lacking any realistic awareness of the nation’s needs and an ability to address them; Trump because of his personality, Biden because of his age.

In short, the way politicians win elections today is not to prove that they deserve to govern. Rather, they persuade the public that their opponent deserves to be punished for their sins or obvious failings.

Analyzing the rather surprising landslide defeat of Britain’s Conservative Party after 14 years of continuous rule, The Guardian’s columnist Rafael Baer explains the result as the “imperative to punish the Tories for years of political malpractice.” He claims it “was palpable on the campaign trail in a way that exultant Starmer fandom was not.”

Today’s Weekly Devil’s Dictionary definition:

Imperative to punish:

A moral sentiment caused by the buildup of a population’s frustration with two things: its powerlessness to influence events and its growing understanding that every government it elects is destined to produce consistently disappointing results.

Contextual note

In theory, democracies hold elections to enable the most creative and constructive elements of the population to make up the governing structures that will ensure collective security and foster conditions of prosperity and well-being. The ideal, in most democracies, has been historically betrayed by the empowerment of parties and their associated factions that have eclipsed “the people” as sources of decision-making. Parties foster the creation of a protected political class whose interests become distinct from the population’s. The existence of a political class fosters the emergence of a courtier class, the myriad lobbyists who enforce the role of private interests over public welfare.

Elections have become the measure of two complementary forms of powerlessness. Democracy itself, as a method of governing designed to convey the “will of the people,” has lost any power it once had. This is compounded by the fact that the ruling elites appear powerless to do anything that doesn’t simply aggravate the existing instability of institutions and, of course, the economy.

Elections, instead of embodying the aspirations of the population, have thus become little more than tools of punishment. That may well be necessary when entire populations judge that their way of life is consistently going downhill and that their social, political and economic culture is becoming seriously degraded. That instinct for punishment could even be salutary, if punishment could be managed with a view to improvement rather than simple rejection.

Historical note

In a famous 1960 essay for The Atlantic titled, “The Imperative to Punish,” David Bazelon introduced the concept of restorative justice as an alternative to traditional punitive measures. Restorative justice focuses on repairing the harm caused by crime and involving all stakeholders — victims, offenders and the community — in the process of justice. In the context of the 1960s, a period of creative reform symbolized by the civil rights movement, the War on Poverty and US President Lyndon B Johnson’s “Great Society,” the idea of restorative justice as an alternative to punishment made sense. But history moved in a different direction.

Concurrently with the reforms, Johnson prosecuted a war in Southeast Asia designed to punish Vietnamese nationalists who might be tempted by socialism or communism as an alternative to the US model of god-fearing capitalism. If foreign policy could be based on punishment, why shouldn’t domestic policy follow the same logic? President Nixon and later Reagan pursued that notion. The taste to punish became the driving force in policy-making, foreign or domestic.

This worked out well for the evolving contours of US political parties. Democrats could seek to punish Republicans for being racist and Republicans could insist on punishing Democrats for “over-regulating” and thereby robbing them of their basic freedoms. Namely, the freedom to use any business practices that weren’t outright assassination or theft to get things done. Polluting the environment, for example, should be allowed when required for commercial success. Those who seek to regulate should be punished.

Starting with the premise of civil rights, Democrats began evolving the rules that ended up defining the “identity culture” that established the practices of “cancel culture.” This became an informal system of social punishment that could include getting people fired from their jobs or simply being inundated with death threats on social media.

No one should be surprised that the “satisfaction” of punishing those you disagree with has taken center stage in the psychology of politics in our modern democracies. The “imperative to punish” cited in Baer’s description of the Tory defeat reminds us of the Kantian concept of the “categorical imperative.” Kant’s ethics that define moral principles as categorical — meaning they admit of no exceptions and leave no room to discuss, examine, negotiate, debate and seek “restorative” solutions — has come to dominate Western thinking, especially in the domain of politics. The case can be made that it has perverted the concept and practice of democracy.

We continue to see its nefarious effects in the field of foreign policy. The now well-documented adamant refusal of Biden’s State Department to consider, let alone engage in, negotiations in any of its provoked wars provides perfect examples of the categorical imperative’s misapplication. The cost so far can be measured in hundreds of thousands of lives in Ukraine and Gaza. But it could reach the hundreds of millions as we move closer to creating the conditions in which a spark can ignite conflagration. Armageddon would be the final application of our most cherished “categorical imperative.”

*[In the age of Oscar Wilde and Mark Twain, another American wit, the journalist Ambrose Bierce produced a series of satirical definitions of commonly used terms, throwing light on their hidden meanings in real discourse. Bierce eventually collected and published them as a book, The Devil’s Dictionary, in 1911. We have shamelessly appropriated his title in the interest of continuing his wholesome pedagogical effort to enlighten generations of readers of the news. Read more of Fair Observer Devil’s Dictionary.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

[Lee Thompson-Kolar edited this piece.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 3,000+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment