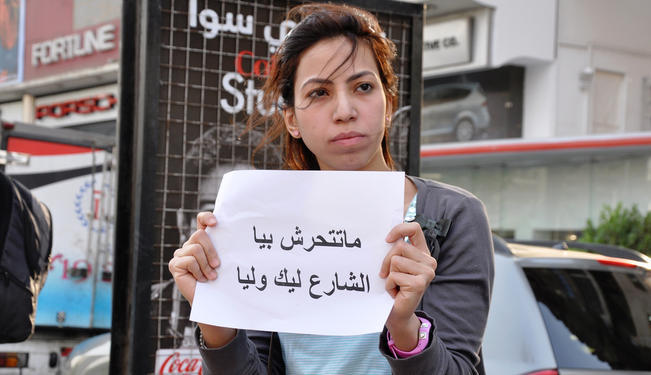

Sexual harassment is endemic in Egypt, and increasing numbers of women have begun speaking out against it. Natasha Smith asks how this deep-seated problem affects women in Egypt and what can be done to stop it.

On June 24, 2012, I nearly died at the hands of a mob of Egyptian men in Cairo. I was stripped naked, dragged, beaten, and violated. For 20 minutes, I was rendered absolutely powerless in a mass sexual assault. A group of Egyptian men eventually fought through the crowd to save me. Inside a medical tent, women helped dress and console me. “This is not Egypt!” they exclaimed. But is it?

I now have the chance to rebuild my life. But what of the women who don’t have this chance? What of the thousands of Egyptian women who face sexual harassment (SH) everyday – how many people hear their stories?

Egyptian Women and Sexual Harassment

“Pick any random woman in Egypt – veiled, young, old, single, married, any age, any socioeconomic class – and she will have stories about sexual harassment,” says Hannah, an anti-SH writer who has suffered sexual assault in Egypt herself. “Some will be less traumatic than others of course, but nevertheless, they will all have stories.”

Tamara is a 33-year-old Egyptian woman. “In the 18 years I’ve lived in Cairo,” she admits, “I can’t even count the number of times I have been sexually harassed on the streets.”

In a 2008 study, the Egyptian Centre for Women’s Rights provoked international uproar by revealing that 83% of Egyptian women had admitted exposure to sexual harassment, whilst 98% of foreign women said they had been sexually harassed while in Egypt. Shockingly, it also found that 46% of Egyptian women and 52% of foreign women faced harassment – from ogling and sexually explicit comments to groping, touching, and stalking – every day. In over 90% of cases, Egyptian and foreign women said harassment occurred most often in the street and on public transport.

“Sexual harassment is a constant part of every woman’s daily life in Egypt,” explains Amira, an Egyptian woman who has spoken out against SH on social networks. “Every single day, I would be harassed – sometimes ten times or more. Men would whistle, whisper, or shout, look at my body and describe what they would like to do with me. I don’t remember a single day when I wasn’t harassed in the street, unless I did not leave the house.”

Such harassment often becomes physical. “Males have stood next to me in metro cars and on buses rubbing their crotches up against me,” explains Vanessa, who lives in Egypt. “Once, in Nasr City, I had to jump out of a moving microbus because the driver kept trying to touch me. I was in the front seat, pressed tightly against the passenger-side door, but his arms were like octopus tentacles.”

“Like When People Torture Animals”

Amanda Zohdy, founder of the Sexual Harassment Action Group (SHAG), is among many who believe SH has become a cultural norm in Egypt. “A culture of acceptance has gradually built up over time,” she explains, “which means that, until very recently, the problem has been steadily growing. Not only men, but a lot of women, felt it was inevitable and a very minor offence.”

Deena, a 21-year-old Egyptian woman, grew up in this culture. “Growing up as a teen in Egypt,” she says, “I spent a lot of time with girls my age casually exchanging stories about our sexual harassment encounters as though we were talking about shoes and make-up.” She told me she was once walking with a friend in the daytime while a taxi driver followed them in his car, masturbating. “A lot of people assume it involves violence or force,” she observes, “which can cause them to overlook more common things like catcalls, obscene gestures, wandering eyes, or unsolicited flirting from strangers.” Because “nobody gets hurt”, she argues, such incidents are perceived as socially acceptable. “Yet they still remind women they are objects, to be ogled by men.”

Khaled is a gynaecologist in Egypt. He believes women do not receive adequate care and support for physical forms of SH because of the “blame-the-victim” attitude within the medical profession. In poorer areas, “she will frequently be accused of having provoked the harassment by her ‘inappropriate’ dress or attitude,” he admits. “The medical profession will usually think they have much more important things to do than to care for a ‘bitch’ who received what she deserved.” Fear of being ridiculed can discourage women from admitting harassment when seeking medical treatment. “Women tend to hide the incident,” he explains. “Even if they show up, they will usually lie about the cause, saying they fell from stairs or were hit by a car.”

Yahia Zaied, of the Nazra Institute for Feminist Studies, emphasises the negative impact of this “blame the-victim” culture. “The harasser knows that he is safe; that everyone will either support his actions or blame the girl. It’s all about power dynamics: the harasser is in a much stronger position and knows he will never be punished.”

Amira feels this lack of punishment enables harassers to toy with women. “It is somehow like when people torture animals,” she claims. “Why do they do it? For their own amusement: because they can. Because the beaten cat cannot defend itself. They believe a woman cannot defend herself and cannot speak up. This is where we have to prove them wrong.”

Child Development

Laila, an Egyptian woman, feels that sexual harassment stems partly from child development in Egypt. “Here in Egypt, kids are raised separately from each other,” she notes. “So when boys grow up they are not used to being around girls, and therefore, don’t know how to think of them in any way except sexually.”

This gender segregation leads boys to consider girls as a forbidden fruit, which can lead to inappropriate conduct. Jonathan Moremi is an anti-SH and human rights blogger and activist who also feels gender segregation is unhealthy in Egyptian society. “Even men in their twenties, deprived of the chance in youth to have learnt to co-exist with female friends, behave like little boys who run and lift skirts, pinch, or do anything that allows a quick flight after the attack.”

May, a young Egyptian woman, recalls swimming in public pools as a child. “I remember boys would do anything to touch us under the water and we would feel helpless and confused. Sometimes, we were lucky and someone would notice and keep them away. If not, there was nothing we could do or say.”

Tamara believes boys replicate behaviour they see elsewhere. “Unfortunately, boys often mimic their brothers, uncles and fathers, who copy their forefathers before them.” She, among others, believes the solution to SH lies in the education of future generations. “Boys need to be taught to respect girls,” Tamara argues, “so that when they become men they respect women.”

Egypt and Gender Equality

A series of high-profile stories over the past 18 months have forced Egyptian women’s battle into the global media spotlight.

An anti-harassment protest on International Women’s Day 2011 ended in outrage after Egyptian men aggressively confronted the women demonstrating, ordering them to return home.Seven women arrested during the protests claimed that they were, during their incarceration, subjected to so-called “virginity tests” by military officials. The invasive, humiliating procedures were intended to degrade the status of female protestors by “proving” that they were not virgins. Although such tests were later declared illegal, the doctor accused of conducting the procedures, Ahmed Adel, was cleared in March 2012 of all charges.

In December 2011, an image and video footage of a young, Egyptian female protester being dragged and beaten by police, exposing her blue bra, went viral.Her treatment provoked thousands of women into protesting, calling for the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) to stand down and demanding an end to systematic abuse of Egyptian women.

In June, an anti-SH protest of around 50 women was hijacked by Egyptian men, who sexually assaulted the female activists. Weeks later, I too was attacked in Tahrir. The subsequent transfer of power after the presidential race has not stemmed sexual harassment.

Lauren Wolfe, Director of WMC’s Women Under Siege, claims such attacks reflect some Egyptian men’s opposition to gender equality. “As greater numbers of women have literally and figuratively gone into the public sphere to protest during and since the revolution,” she notes, “their presence has provoked those who believe women should be (barely) seen and certainly not heard.”

Arab Women in Politics

Amira is among many who link sexual harassment in Egypt to the patriarchal nature of Egyptian society. “The man’s role is so clearly dominant, it is ridiculous. Men are superior in the law, business, politics, and social life, and they take this to the streets.” This widespread disparity between the sexes was illustrated in the 2011 Global Gender Gap Report, where Egypt ranked 123rd out of 135 countries.

In politics, Egypt suffers a phenomenal gender imbalance. A Mubarak-era quota ensuring a minimum of 12% (64 seats) representation for women in parliament was dropped following the revolution. New legislation has since brought about a decline in female representation to just 2%. This is a disappointing step backwards at a moment when the Arab world most needs to increase women in parliament; a recent study showed that the Arab world is the only part of the globe lacking a parliament with at least 30% female representation.

Wolfe believes increasing female political participation is critical. “It’s crucial that women receive greater representation in the political realm. Without women’s voices at high levels, we’re stuck with whatever patriarchal norms conservative men want to propagate.” Women are four times more likely to be unemployed, whilst those in the workplace stand a pitiful 2.8% chance of reaching managerial positions. Clearly, their voices are not being heard.

A Growing Tide of Opposition

The anti-SH movement is gaining momentum, especially online. “A year ago today, we rarely had anyone speaking out defending victims of sexual harassment,” says Hannah. “Now, for every mass sexual assault in Tahrir, there’s a thousand-person protest demanding respect.” Holly Kearl founded Stop Street Harassment, an online campaign to raise awareness of harassment. “I am always impressed and amazed by the variety of actions people in Egypt are undertaking to address this problem,” she comments. “They’re doing so much online, as well as demonstrations, graffiti and other actions, to take this issue to the streets.”

During the Eid festival, Nihal Zaghloul helped organise anti-harassment patrols of the metro. She describes how it felt to fight SH in a male-dominated group. “It felt great. After years of watching alone and not being able to do anything because you are outnumbered, we gathered and formed a unit, making us, the majority, able to stop them.” It is vital for men in Egypt to support the anti-SH movement. Sherif Amer, a young Egyptian man, feels “it is a matter of honour” for every man in Egypt to defend women against harassment.

Many in Egypt believe police must prevent and punish harassers much more severely. “There are no negative consequences whatsoever for harassers,” says Amanda. She argues that the police should create a specially-trained force to deal with SH, with at least 50% female officers. Yahia Zaied feels police must work together with anti-SH groups. “I believe we have reached a point with SH where we need to highly criminalise it, ensuring that the law will be applied in parallel with our work on the ground to raise awareness and change this culture.”

Moremi is among many who believe that a mass public education campaign, to cover the media, public transport, and in schools, is critical to preventing SH. “Imams, priests, ministers, teachers, journalists – all have to join hands in this in setting the tone right in society so that SH becomes the most despicable behaviour,” he asserts. “Respect for women must be demanded publicly by those public figures.”

Abdelfattah Mahmoud worked with Nihal to organise the metro patrols. He believes any awareness campaign must target women and girls. “Every woman should know her rights at an early age as part of her education in school,” he argues. “She must be raised to know she is more than a sex object and that man is not her superior, but her equal.”

Men and women are joining the fight against harassment in their thousands, yet the battle is not yet won. “Sexual harassment is literally killing us,” says Amanda. “I want to be able to laugh, sing, look people in the eye, smile and swing my hips. It’s my simple birthright and I’m determined to have it.”

For an entire nation to rethink its attitudes, the rest of the world must support Egypt’s women. “Those of us outside Egypt have a duty to the women who have to face abuse and harassment daily,” says Wolfe. “We have to stand for and with them. When half the population is sexually harassed, intimidated, and violated, it is a human rights issue that must concern everyone.”

If this is Egypt, then it will not be for much longer. The tide of opposition is growing ever-stronger, and the world is beginning to take notice. My attack prompted a global response that I could never have imagined. Now let the world listen to the thousands of Egyptian women who for too long have been silenced. Egypt fought through one revolution, and it must now unite in another: a revolution for the women of Egypt.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment