After appraising the milieu of the recent coalition Paris meeting regarding the Syrian humanitarian crisis, Laurenti argues that “the layering in of international military monitors, including some from Russia and China, plus a large humanitarian relief operation… “are the most efficacious policy options moving forward”.

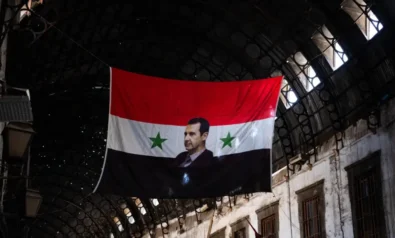

The Paris meeting this month of the international coalition supporting the ouster of Syrian president Bashar al-Assad, sent a clear message to Russia, his chief defender in the United Nations Security Council: We are not wedded to Kofi Annan’s peace mission, and if you can’t put the leash on Syria’s attack dogs, we are ready to up the ante.

The self-styled Friends of Syria acknowledged that the UN-Arab League special envoy’s plan was “a last hope” for averting Syria’s slide into conflagration. But they have read the Syrian government’s failure to fulfill its commitments under Annan’s six-point program, a week after it was supposed to be in effect, as a sign that the Baathist leadership remains convinced it can ride out the storm.

While it is important for both Washington and its anti-Assad allies to ready a contingency “Plan B” in case the peace effort does fail—just having one in reserve can deter the Damascus authorities from aborting the peace initiative—the “Friends” should not be in unseemly haste to bury it alive. This may prove a slow-motion peace-making process, but it remains the only alternative to a chaotic war.

Patience does not seem in vogue in Paris right now. “We cannot wait, time is short,” French foreign minister Alain Juppé said yesterday, three days ahead of France’s first-round presidential election. And the Annan mission? We “have to give it a chance for a few more days.”

Then what? Juppé’s politically imperiled president, Nicolas Sarkozy, demands “the creation of humanitarian corridors so an opposition can exist in Syria”—a curiously Orwellian pairing of “humanitarian” and “opposition” that would necessitate an outside military intervention, which France is apparently incapable of undertaking.

Still, Juppé has emphasized France’s recognition that Security Council authorization is required for any use of force from outside, which means getting Russian support. US secretary of state Hillary Clinton similarly acknowledged that UN approval is necessary for her preliminary “Plan B” remedies of a global arms embargo on Syria, travel bans on its leaders, and financial sanctions—which Russia would surely veto today but might accept, she thinks, if Damascus stonewalls the peace-making process.

One could bypass the Security Council by the incendiary step of directing arms shipments to the insurgents, as the Saudis and some hawkish US senators continue to propose, and hope (a) that the recipients do not prove to be mujahedin extremists, and (b) that they win.

But, as analyst James Harkin warns, “if the Saudis and the Qataris are allowed to funnel unlimited cash and weapons through the country’s traditional smuggling routes, the likely result will be to empower a crooked new class of arms-dealing middle men and the kind of fringe Salafist groups that are quite happy to turn themselves and everyone else into martyrs for the cause.”

Russia is, as Clinton tacitly admits, in the driver’s seat on Syria. As one of Syria’s last allies and arms suppliers, it uniquely has influence with the government, and it sees a soft landing from the Syria turbulence as crucial to its own aspirations to count for something in the Middle East. The Russians’ inhibitions determined the parameters of the Annan mission, and they are deeply invested in its success.

With the ink barely dry on an initial agreement between the United Nations and the Damascus authorities on the deployment of the UN monitoring mission, Russian foreign minister Sergey Lavrov, meeting with his Italian counterpart Giulio Terzi, signaled urgency to adopt, “as soon as possible, a second resolution that will approve a full-scale observer mission” of at least 300 military observers.

Intervention-minded Westerners and Arabs suspect the Russians see the monitors cynically as simply window-dressing to allow the government to play for time to try again to exterminate its opponents. This surely is wrong.

The Russians recognize that Assad’s security forces have already tried extermination in the past few months, leaving the insurrection bloodied but unbowed. And perhaps they are not paranoid in perceiving that “some, including outside Syria,” in Lavrov’s words, “would like to spoil Annan’s plan.”

Italy’s Terzi insists that Lavrov is “an effective partner in the search for a way to end violence and carry out checks on the ground that the ceasefire can hold.” One sign is Russian backing for the UN monitors—trained for the task, unlike December’s Arab League monitors—to provide the international community with professional assessments of compliance and violations.

The agreement that Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon and the Russians both want swiftly consecrated in a Security Council resolution requires the Syrian government to fulfill the Annan commitments and ensure the safety of all UN personnel, “unhindered access of UN personnel to any facility, location, individual or group considered of interest,” and maintenance of security through regular law enforcement agencies and not the military. It would also bar the armed opposition from displaying weapons, setting up checkpoints, or conducting patrols.

Still up in the air is the UN’s insistence on its monitors’ freedom to travel in their own aircraft. The United Nations is also seeking to wrap up an agreement for a major UN-led humanitarian aid operation (sans Sarkozy’s military corridors) to address what even Damascus acknowledges are “serious humanitarian needs.”

There are security risks, as Annan’s deputy Jean-Marie Guéhenno advised the Security Council Thursday, in sending unarmed monitors into a combat zone. And there are political risks, as each side attempts to manipulate the monitoring mission to its advantage. (The Moroccan head of the advance unit of monitors was visibly uncomfortable when activists walked him through a chanting anti-Assad crowd in their tight embrace.)

But the layering in of international military monitors, including some from Russia and China, plus a large humanitarian relief operation, is the best hope for consolidating what over the past week has been a shaky ceasefire, providing insulation against Syria’s reversion to the spiraling violence of late winter, and—hardest of all—prodding the deeply antagonistic Syrian parties to negotiate an open and inclusive political settlement.

*[This article was first published on Huffington Post.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment