“That which does not kill us makes us stronger.” The German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche didn’t have the afflictions of athletes in mind when he wrote this, though many athletes who have surfaced from depression actually appear to be fortified by the ordeal. Others suffer, often in silence, and never fully recover.

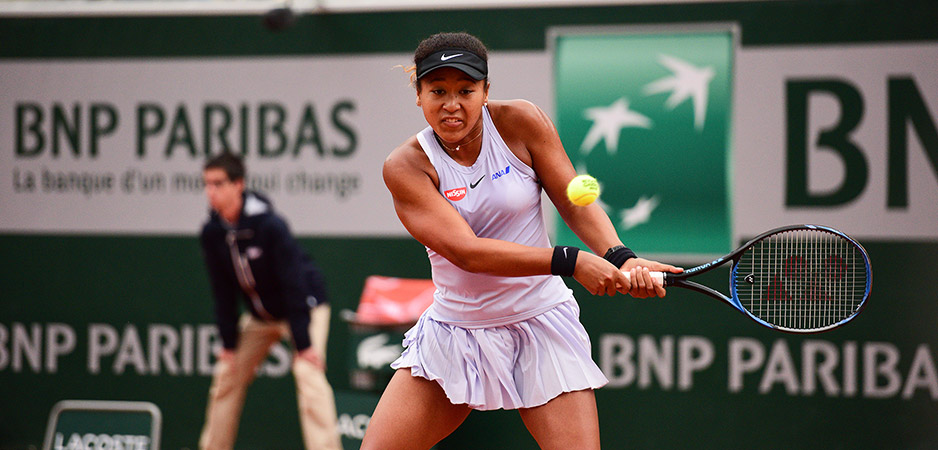

We don’t know how Naomi Osaka, the world number 2, will react to “the long bouts of depression” she has experienced since 2018. The Japanese tennis player was a 20-year-old when they started. She is now 23 and faces something of a crossroads, having withdrawn from both the French Open and, more recently, the WTA German Open. She now has to decide whether to enter Wimbledon, which starts on June 28.

Osaka may storm back powerfully, bursting with confidence and fresh resolve, as Nietzsche would have predicted. She could also recede into obscurity, like another young tennis player, Andrea Jaeger, who was ranked number 2 at the age of 16 and looked set for superstardom, but retired at 19 in 1986, a victim of what was then called “burnout.” Now, we have a more sophisticated understanding of why some professional athletes, particularly young ones, suffer inwardly: anxiety, stress and depression that affect the rest of the population may be more prevalent in sports.

Athletes operate in a risk-riven, competitive environment that deliberately cultivates aims, targets and achievable goals. Reaching goals is rewarding, but falling short can be devastating. Even a single defeat can be ruinous. There is also a ceaseless series of expectations. Literally everyone, from the people who serve in the canteen to journalists who report to the media, harbors expectations. In themselves, expectations have no potency, but the manner in which competitors assimilate and respond to them is crucial. Some athletes thrive, while others wither. Responding to the expectations of others is the mainspring of depression. Yet, sometimes, the condition seems unrelated to athletic performance and is barely intelligible.

Robert Enke

The case that alerted the world to the problem of mental illness in sport was that of 32-year-old Robert Enke, one of Germany’s leading football stars. Widely tipped to be the number-1 goalkeeper in the national squad for the 2010 FIFA World Cup, Enke walked onto the tracks in front of an oncoming train in 2009. The football world was stunned: why? After all, he was an affluent, young sports celebrity with a chance of winning one of the most coveted prizes in sport.

Enke’s wife, Teresa, revealed that he had been tormented with depression for years. He tried to hide his mental condition, fearful it might damage his professional career. Worse, he thought it might cause authorities to take away his 8-month-old daughter, whom he and his wife had adopted earlier in 2009. The couple lost their 2-year-old daughter through a rare heart condition in 2006.

As a youth, the precociously proficient Enke was often required to play in teams with older players and his father, Dirk, told how his son grew anxious. “There were always crises back then because he was scared that he would not be able to keep up with the older ones …He did not have faith in himself,” Dirk said in 2009. Of course, most top athletes do have faith in themselves. They are usually self-confident and often ebullient. Or at least they appear to be. Enke probably did too. Like other athletes, he learned to conceal his apprehension.

Medicalizing Mental Illness

Athletes are coached to do this: If they can’t hide their emotions, they won’t last long in sports. This should make us wonder not why there is so much mental illness in sports, but why there is so little. In the 20th century, mental illness carried a stigma, especially in sports. But we’ve now transmuted what was once seen as a weakness into an illness, much like physical ailments. The process is known as medicalization: We treat mental illness as we would diseases. Whether or not the reader accepts that depression and associated mental disorders are, in fact, illnesses or just cognate — that is, related in certain respects — to illnesses, the reality is that this is how they are diagnosed and treated.

Today, issues and problems that have origins in social, cultural or environmental conditions are viewed and treated as medical ailments. One of the beneficial consequences is that much of the disgrace has been removed, leaving athletes who have suffered to open up about their experiences. They share a common matrix: a culture that inhibits, yet promotes illness. The ethos of mastery, striving and bearing pain mitigates against admitting a susceptibility to attacks that can neither be seen nor beaten with sheer persistence or the kind of hard work urged by coaches. The same ethos fosters ambition and an achievement orientation satisfied only by levels of attainment reached by the elite few.

Most sports careers involve unexpected reverses brought about by defeats or injuries. Mental health problems are regarded in a similar way to an anterior cruciate ligament injury: fixable. Tyson Fury first won the world heavyweight title in 2015. He then sunk into depression and binge drinking, but resumed his boxing career with renewed vigor. Kelly Holmes self-harmed with scissors for two months in 2003. A year later, she won two gold medals in the 800 meters and 1,500 meters at the Olympics. Five-time Olympic swimming gold medalist Ian Thorpe lost motivation completely, retired in 2006 but later returned, yet without ever finding his best form.

Some never quite recover. Michael Yardy interrupted his tour of India with the England cricket team, suffering from depression in 2011. He didn’t play for the national team again. Other athletes, such as rugby’s Jonny Wilkinson and cricket’s Marcus Trescothick, simply lived with mental health conditions from childhood and learned to tolerate the symptoms to a greater or lesser extent.

Who Wants to Be a Sports Star?

Of the myriad causes of mental illnesses, Naomi Osaka’s is unusual: She says finds the media demands unbearable. Major sports are now part of the entertainment industry and their stars are warrantable celebrities. Audiences want access to all parts of their lives, public and private. Osaka has made her commitment to Black Lives Matter clear. She may feel that, as a black woman, she is inordinately questioned about her loyalties, though she hasn’t said as much and appears comfortable making her convictions known.

But she won’t expect any special considerations from tennis authorities, who broker lucrative broadcasting and sponsorship deals on the understanding that players will cooperate. Osaka is presumably bright enough to realize that much of the $37 million she earned last year was made possible by her media presence. Actually playing sports is just part of the Faustian pact.

All of which prompts an obvious question: Who would want to be a top sports star in an environment so competitive that mental disorders go with the territory? There are obvious benefits: money, fame and a job that pays for doing something you would have probably carried on doing for fun even if you weren’t getting paid. But the point about pursuing something for fun is that you don’t get paid for doing it. Once you do, it becomes a job of work. Many, perhaps most, athletes don’t enjoy competing. Andre Agassi famously hated tennis. Other athletes, including Barcelona’s Lionel Messi, are physically sick before competitions.

In May, Olympic bronze medal-winning hammer thrower Sophie Hitchon announced her retirement, aged 29. “I have never really done it for the love of the sport or the enjoyment,” she explained. “I do it because I was good at it, and was succeeding at it.” Hitchon’s approach may not be representative, though I suspect it is.

No rational person willingly wants to train repetitiously every day, risking physical injury, sometimes resulting in death and always facing the possibility of mental indispositions — unless they are succeeding and, presumably, making a good living from it. The recent life-threatening cardiac arrest suffered by Denmark’s Christian Eriksen at the UEFA European Championship reminds us that being fit, well-dieted and regularly tested is no defense against the intensity of constant competition. Polish footballer Robert Lewandowski recently issued the reminder, “we’re humans, we’re not machines.”

So, Osaka’s options are either to overcome her anxieties with the media or cease playing, at least till such time when she is able to cope. This sounds like a pitiless pair of options, but there seems little latitude. Her premature retirement would be an awful loss to tennis. But is money and success worth it, if the price is her mental health?

It’s not a rhetorical question: Many athletes and entertainers persist with their careers despite depression. They include Katy Perry, Bruce Springsteen and Gwyneth Paltrow. All three have found relief, sometimes through medication or therapy. Lady Gaga has integrated her experiences with mental illness into her work. At 35, she is the youngest of the group. It’s an age when most athletes have either retired or are contemplating it, and perhaps the relative brevity of a competitive career increases the mental duress. I don’t know whether these entertainers would endorse Nietzsche’s apothegm, but all of them have had long, garlanded careers. Mental illness didn’t become a salient influence on any of their lives.

Mental health is a corner of the sports landscape that was ignored for many decades. While a fuller understanding of the causes of depression involves analysis beyond the physical, the newfound confidence of athletes like Naomi Osaka to disclose their mental problems is due in large part to a medicalized understanding of its status and public acceptance that it is treatable.

*[Ellis Cashmore is the author of “Kardashian Kulture.”]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.