Given the restrictions introduced to curtail the global spread of COVID-19, many people are experiencing significant changes to their eating habits. Current regulations are affecting both local and global supply chains. Even in the regions where they remain stable, fear of shortages during a lockdown prompted many to stockpile food. In mid-March, the media worldwide posted pictures of empty supermarket shelves, which only encouraged further panic buying.

Now, citizens around the world must limit their visits to supermarkets to an essential minimum. Online shopping is no longer an alternative as waiting times for deliveries can be weeks long. In many countries, restaurants are closed, and even ordering a takeaway is no longer possible. Hence, many people are turning to canned foods and dry goods instead of typical, day-to-day purchases. Working from home, they need to prepare their own meals. School closures in many countries mean that parents have to provide nutrition for whole families around the clock.

Unhappy Meat

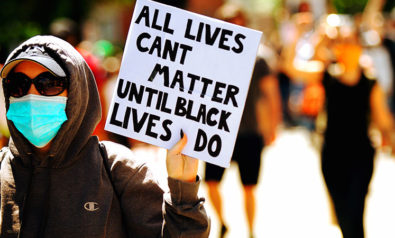

This is a good time to reflect on our personal food preferences and habits, as well as the global system of its production and consumption. After all, the novel coronavirus seems to have first appeared at a food market in Wuhan, China. It is widely assumed to originate in bats, with pangolins being the intermediary in transferring the disease to humans. Pangolin, the most trafficked animal in the world, is a delicacy in China. Its scales are thought to have healing properties, which poses a further threat to this nocturnal mammal. Its poor vision makes it easy prey for poachers.

The custom of selling living animals at markets, often located in urban settings, seems horrific to the Western world. Probably the biggest difference is that such practices undermine the “happy meat” approach to production and retail adopted in the West. It argues that the regulation of farming and slaughtering conditions is enough to render meat consumption morally unproblematic. This position holds that industrial livestock production does not need to conflict with animal welfare. Its best articulation is the EU’s aim to ensure that animals do not endure avoidable pain or suffering. The question of which types of suffering are unavoidable remains open.

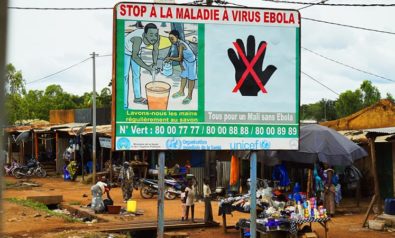

However, a zoonotic disease pandemic — one in which an infection is passed from animals to humans, like the current coronavirus — indicates clearly that animal welfare and human welfare are interconnected. Many potentially deadly human diseases originated in animals. While some of them, like rabies or Zika, are not related to farming practices, many of them are.

The rapid increase in global meat production translates into a constantly increasing risk of spreading existing diseases as well as of the emergence of new ones. Animal farming relies on an unnatural diet, with breeds lacking genetic diversity and enduring prolonged stress, making them especially prone to infections. High population density and poor sanitation make meat production and retail sites potential sources of new outbreaks.

Contrary to popular belief, the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic, which took place long before the achievement of the current intensity of meat production, originated not in Spain — the country hit hard by the disease, thus giving the epidemic its name — but on a chicken farm in Kansas. Meat industry employees, often low-skilled and unaware of the biological risk, work in extreme temperatures and are regularly exposed to animal secretions. The system creates not only incubating zones for viral infections, but also potential super-spreaders.

Struggling to maintain our eating habits under extensive restrictions, we may take this opportunity to adjust them. In these dystopian times of spatial distancing and the curtailment of freedoms, we can choose to voluntarily change our approach to food. Thus, we could contribute to one undeniable positive effect of the COVID-19 pandemic — that upon the environment. However, if the big-cause incentive is too broad to be convincing, there are more reasons to change to a plant-based diet.

Why Not Eat Vegan for a Change?

Firstly, it is practical. Changes in grocery supplies and purchases mean that many people have to cook inventively, using the products available and not what they would typically buy. Relying on meat and dairy increases the risk that some of the key ingredients will not be available. The more types of products we include in our diet, the easier it becomes to compose healthy, sustainable meals. It is a great way to include new flavors in the daily menu when cooking and eating becomes monotonous.

A plant-based diet also helps to reduce the frequency of buying groceries and to optimize their storage, as essential ingredients such as legumes, nuts, seeds or nutritional yeast have long shelf-lives and do not need to be refrigerated. They can be purchased in larger quantities without the risk of being wasted.

Secondly, it improves time management. Extra time to cook at home may be used for experimentation. And, conversely, if reducing the time spent in the kitchen is the goal, vegan dishes are suitable for meal prepping since they are often less perishable than animal-based products.

Thirdly, cooking is a great way to deal with the current confinement. Studies in psychology suggest that taking up a new activity or learning a new skill gives us a sense of self-agency and control. Exploring vegan cuisine could also foster interaction with the vegan community online and promote an exchange of ideas in times of spatial distancing. Self-isolation is a time of tranquility as much as it is a time of uncertainty and concern. It offers time and space to question our choices and priorities.

If eating a pangolin is unimaginable to many of us, so could be the consumption of other animals. When we are all forced to change our lifestyles and reconsider our priorities, one more change may seem to be less of a challenge. Or, if challenges and new projects are what one needs in isolation, going vegan could be a good start in preparation for the inevitable future outbreaks of similar diseases.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.