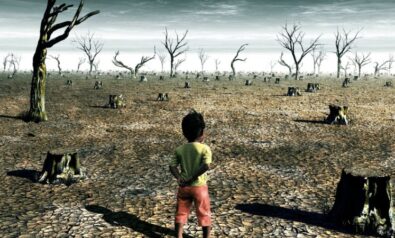

Despite the overwhelming scientific evidence of climate change and its effects, many people are still skeptical.

Climate change, its causes, its effects and how we should respond globally and individually are arguably one of the most divisive and challenging issues of our time. There is considerable and compelling scientific evidence not only for the causes, but also for the long-term effects of climate change. Yet despite this, a global agreement among nations has been very difficult to attain. Despite the overwhelming scientific evidence, and explanations of what climate change is and how human activity is significantly contributing to it, the world is struggling to make the changes required to avert its inevitable effects on humans for generations to come.

There have been numerous global actions to coordinate and organize scientific consensus and global actions through agreements. Not least of these are the publications of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and the activities of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

Despite these positive global initiatives and considerable efforts to consolidate the science on climate, and despite the efforts to agree on equitable and workable actions to reduce emissions of greenhouse gases, we are nowhere near the targets needed to reach the levels of greenhouse gas reductions to minimize the potential catastrophic impacts.

There are many fundamental lessons to learn from the failure of the scientific community to communicate the messages, and for policymakers to act. These lessons may, in future, assist in dealing with other major global issues such as food and water supply, mass migrations, Internet-related problems, child pornography, human trafficking and others requiring globally coordinated actions and agreements.

It is interesting and important to explore the human behavioral and psychological aspects of climate science rejection. This is the first of a series of articles that provides a short summary of the various reasons for the rejection of the science (by some) and the complexities of developing and implementing appropriate global policies and actions. Where appropriate, reference is made to the relevant studies to allow for further research. Ultimately, it is hoped that a better understanding of the reasons for the rejection of, or difficulties policymakers and a minority in the general public have, in accepting the science of climate change and the urgency required for global action.

Background

As an environmental management consultant over the past 30 years or so, and an advisor in energy efficiency, climate change risk management, greenhouse gas management and sustainability, I, like so many others, have been frustrated by the lack of adequate global action and agreement on greenhouse gas abatement mechanisms and policy. It is clear that while there has been some effort and agreement to take action (such as the Kyoto Protocol and the latest deal following the 21st Conference of Parties), such actions have been patchy at best. But even more than frustration, there are a number of behavioral patterns in those who reject the science of climate change. The recurring question in my mind has been: Why do some people reject the science of climate change?

It is important to analyze the international community’s (and in particular, some leaders’ responses) to the threats of climate change as it may teach us a few lessons, and tell us how we should galvanize public opinion and address other global policy issues. The context of my analysis is this: Many studies have shown that the demographic of climate change denial has a significant peak for the “white, male and over 50” group. As this group has dominated (and still dominates) those in power, and particularly those making decisions on climate change policy, it is worth looking at the reasons for the rejection of the science and the lack of global agreements.

Before we begin, it must be recognized that the science of climate change is very complex. And although I believe that the scientific community could have done a much better job of explaining the basic scientific facts behind greenhouse gases and their impact on the climate, it has not been an easy task. Any discussion or explanation of climate change is complex due to the many elements of greenhouse gas emissions, the natural climatic patterns and the very complexity of how the climate behaves.

The Earth’s climate includes the oceans, wind, the biosphere, upper and lower atmosphere, solar effects, glaciers, clouds, evaporation and so. Add to these the complexities in determining the long-term historical average temperatures of the Earth, and predicting future temperatures based on very large number of assumptions parameters and variables.

The study of climate change, therefore, involves the advancement and integration of our knowledge in all these areas of science, which individually are very complex. This complexity has contributed to the high level of misconception and misunderstanding by the general public, by the media and even by those in positions of power. Its complexity has also contributed to the difficulties experienced by the scientific community to fully explain the science and convince the global community in a cohesive and comprehensive manner.

Part of the complexity is the long-term trends and, at times, non-intuitive issues that have to be understood and accepted by the general public. For example, it is very difficult for the general public to understand why and how a degree or two or even three increase in the global average can have such catastrophic impacts on the climate. It is also very unintuitive for the general public to understand why we still have very cold winters when there’s global warming.

Adding to the barriers to global action on climate change are the very complex and enormous challenges in the development of equitable, fair and balanced actions that can be agreed upon by all nations and economies. Not least of the complexities are the wide gaps that exist between the developed and developing economies, the historical responsibilities and “ownership” of the atmospheric greenhouse gas emissions, and the enormous future costs of actions required to considerably reduce global emissions.

While accepting and being mindful of the many complexities and challenges, I have come up with a number of thoughts and theories, some quite unusual, in trying to understand why some people find it difficult to accept the science of climate change.

The need to belong

This is what normally happens to me. I’m at a private or public function. I’m introduced to someone who asks me what I do. I explain that I’m an environmental management consultant and a specialist in climate change and energy efficiency. Almost before I finish my explanation of what I do, my listener who is invariably male and over 50, interrupts me to say something like, “I don’t believe in climate change.”

Most go beyond that and say something like, “I think it’s a rort, a sham” or words to that effect.

I’m so used to this that I don’t react, and without changing my tone or showing any emotion, I ask the person, “… and what expertise in climate change do you have? Have you done a lot of reading on this topic?”

Without exception, the response is, “I actually don’t have any expertise; I just don’t believe it.”

Again, I don’t react. I stay calm and ask for further clarification saying, “What gives you this belief? Is it the science that you don’t believe?”

Again, I either get a shrug of the shoulder or silence, so I continue trying to understand this person’s reasons for not accepting or not “believing” the science, and I ask, “… and if it is the science you can’t accept, what would it take for you to be convinced?”

Invariably, I’m not given a valid reason, and I’m told, “I just don’t think climate change is happening, and even if it is, I don’t think humans are responsible for it.”

The above conversation, or similar, has taken place so many times that I am astounded by the consistency and regularity of it. It is this consistency that has made me investigate and research the reasons, and the psychology behind it. These types of responses are even more astounding when I consider that the vast majority of the people I’m referring to are seemingly intelligent, educated and generally well read and traveled.

Here is my explaining of it in terms of branding, of identity and of belonging. Humans are essentially and necessarily social animals, and the need for belonging to a mob or a tribe has been, and still is, vital for identity and our instincts for survival, dating back to the time when we lived in caves and hunted and gathered in groups. This instinct appears more prevalent in males and particularly those with some sense of responsibility—the “baby boomers.” There are many badges we all wear to belong to a group or mob; the sporting team we follow; the religious group we belong to; where we live; even the type of food we eat.

I cannot find any other reason why a polite, intelligent stranger, having just met me, and even after knowing that I have spent my entire professional life pursuing sustainability and have considerable understanding of climate change, would hasten to tell me that it’s a sham and that it does not exist. This is, in modern terms, a branding exercise on a personal level. It is a “badge of honor” that people want to wear, similar to belonging to a club, or a religious group and the like. It’s why people wear the colors of their sporting team when they go shopping, wear religious clothing, dress in “gothic” style, etc.

Humans are fundamentally social animals and need to belong to a tribe. It’s part of our survival instinct. Belonging to a tribe has been vital to our survival and development. In modern times, thousands of years after leaving the cave, we still have the need to belong. It helps shape our identity and self. And we do this through religious groups and affiliations, sporting clubs, political parties, environmental groups, social and many other groups.

While many other global issues such as child pornography, pedophilia, human trafficking and slave labor do not allow “camps” of views, climate change allows a number of camps. Here are some of the climate change camps or clubs that one can belong to:

1) Total acceptance of the science and the significant contribution of human activity to climate change, and acceptance that urgent action is needed;

2) Acceptance of climate science and that human activity is contributing to it, but also that we can’t do anything about it, it’s too far gone and too difficult. Let future generations and new technologies deal with it;

3) Acceptance of climate science and that human activity is contributing to it, but also that the contribution of human activity to climate change is insignificant or not large enough for major action and sacrifice;

4) Acceptance of the science of climate change, but not accepting human activity’s contribution to it; it’s a normal cycle of climate change that the globe has been experiencing for many millions of years;

5) Non-acceptance of climate science and whether it’s happening at all;

6) Non-acceptance of climate science and whether it’s happening at all, indeed that it’s a conspiracy by those who want to destabilize developed economies.

Unlike the other global issues nominated earlier, climate change allows people to belong to the camps above.

In the next article of this series, I will explore other reasons for the difficulty that some people have for accepting climate change science.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Photo Credit: Bernhard Staehli / Frederic Legrand – COMEO / Shutterstock.com

We bring you perspectives from around the world. Help us to inform and educate. Your donation is tax-deductible. Join over 400 people to become a donor or you could choose to be a sponsor.

We bring you perspectives from around the world. Help us to inform and educate. Your donation is tax-deductible. Join over 400 people to become a donor or you could choose to be a sponsor.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.