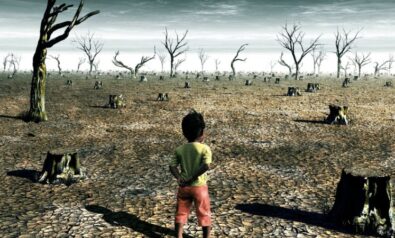

Climate change deniers often claim that there isn’t enough evidence to support global warming. Arek Sinanian explains in part two of this series.

In my last article for Fair Observer, I explored one of the reasons for the denial of climate change science. In this article, I explore two others.

Despite the overwhelming scientific evidence of climate change and its effects, many people are still skeptical. While the number of skeptics may be diminishing, there are lessons we can learn from the failure to galvanize consensus and acceptance of the science, and the resulting slow progress on global actions to tackle climate change and minimize its effects.

This is the second of a series of articles, in which I explore some of the reasons for such skepticism by some.

The Dunning-Kruger Effect

We have always known the adage “a little knowledge is a dangerous thing.” Well, a highly credible scientific paper published by David Dunning and Justin Kruger concluded that people tend to hold overly favorable views of their abilities and knowledge in many social and intellectual pursuits.

The authors suggested that this overestimation occurs mostly because people who are unskilled in certain pursuits suffer a double problem: Not only do these people reach wrong conclusions and make inappropriate choices and decisions, but their incompetence prevents them from realizing it.

Across a number of studies, the authors found that participants scoring low results on tests of humor, grammar and logic significantly overestimated their test performance and ability. For example, people with test scores in the 12th percentile estimated themselves to be in the 62nd percentile.

I might know a thing or two about making wine, and when asked to rate my knowledge of wine making, I might score myself say eight out of ten. But in reality, my knowledge may only rate me a five at the most.

In a way, the tests proved that people usually don’t know enough about a topic to realize that they don’t know much about it to make appropriate and rational decisions about it. Paradoxically, improving the skills of the participants, and thus increasing their competence, helped them recognize the limitations of their abilities and knowledge. In other words, people who know very little, think they know more than they actually do, while those who know a lot, think that they know less than they actually do.

Admittedly, the Dunning-Kruger studies did not specifically test for knowledge of climate science. And a skeptic’s disbelief in climate change isn’t a simple matter of one effect or influence. However, I can’t help but to attribute at least part of the many reasons of the “disbelief” in climate change science by many skeptics to this effect.

I have on numerous occasions been confronted by people who say to me, “I don’t believe in climate change,” and when I ask them how they came to this “belief,” and whether they have special expertise in the field of climate change science, they openly admit that they are not experts, and generally cannot explain where the basis of their conviction comes from.

Usually I’m given a brief summary of articles or details that are available on certain websites and, more often, the very limited knowledge on climate change is obtained from newspaper articles, or from highly biased and “cherry picked” references or unpublished and non-reviewed articles. Cherry picking or selectively drawing on isolated papers that challenge the consensus to the neglect of the broader body of research is often used to argue against a number of scientific issues.

This is also a factor in what is known as Illusory Correlation and Confirmation Bias, which is explained in the next section.

There is another test I sometimes provide for those who confront me with their “disbelief” of climate change science and it is this: I ask them, “You’re telling me that there has always been climate change and you don’t believe it is any different now than it has been for millennia. What will it take for you to change your mind? What evidence do you need to prove that climate change is actually happening and that human activity is contributing to it?” I have yet to be given a rational answer by such a skeptic.

Confirmation Bias (or Cognitive Dissonance)

We all suffer from confirmation bias (or cognitive dissonance) to some extent. It is the tendency to confirm, rather than falsify, one’s own belief system. Since the pioneering research of Peter Watson conducted in the 1960s, we know that we all put far more emphasis on evidence that corroborates our own beliefs, and pay far less attention to evidence that disputes them.

The result is that through a number of behavioral tendencies, we all make sure that our belief is always strengthened—regardless of its validity. The effect is stronger for emotionally charged issues and for deeply entrenched beliefs.

Testing has showed that confirmation biases are prevalent in all levels of intelligence. In fact, some psychologists even think that intelligent people are more susceptible.

A large reason for confirmation biases is related to how we encode and recall memory. Testing has showed that our memory is naturally skewed to recall memories that confirm our thoughts and feelings, especially if those thoughts and feelings are felt particularly strongly at that moment in time.

There are numerous ways we do this. One type of confirmation bias all of us are guilty of is the process by which we give undue weight to early evidence (also known as the irrational primacy effect). By accepting early information, we risk creating a bias that affects our view of any later evidence. It seems that once our belief system is formed, it is difficult to change it. It has been shown that even when early evidence is later proven to be false, we still retain the original bias and our outlook is continually skewed. The climate change discourse has certainly not been helped by exaggerations and reports that were misinterpreted by self-interested bloggers and journalists.

An interesting recurring experience for me is this. When I’m confronted by a skeptic who clearly has based his or her opinion on climate change on confirmation bias, I offer to explain the scientific mechanisms by saying, “Give me ten minutes and I’ll explain the chemistry and physics of greenhouse gases, which will then give you a much better understanding of how climate change happens.” I’m yet to be given the opportunity.

How often have you heard climate change deniers claim that there isn’t enough evidence to support global warming?

This is known as disconfirmation bias: When we are presented with evidence that disputes our beliefs, and we then hold that evidence to a higher standard. We suddenly start to dispute the thoroughness or the impartiality of evidence, in a way we would never do for evidence that does not dispute our pre-conceived beliefs. A disconfirmation bias is particularly tricky to spot because, in your own mind, it can give the impression that you are indeed being thorough and scientific.

Explanations for the observed biases include wishful thinking and the limited human capacity to process information. Another explanation is that people show confirmation bias because they are weighing up the costs of being wrong, rather than investigating in a neutral, scientific way. And the costs of climate change and our responses are so economically, socially and morally devastating that confirmation bias is a much easier way out.

These are only some of the reasons for climate change denial. In the next article of this series, I will explore other reasons for people who find it difficult to accept climate change science.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Photo Credit: Lassedesignen / Sylvie Bouchard / Shutterstock.com

We bring you perspectives from around the world. Help us to inform and educate. Your donation is tax-deductible. Join over 400 people to become a donor or you could choose to be a sponsor.

We bring you perspectives from around the world. Help us to inform and educate. Your donation is tax-deductible. Join over 400 people to become a donor or you could choose to be a sponsor.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 3,000+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Commenting Guidelines

Please read our commenting guidelines before commenting.

1. Be Respectful: Please be polite to the author. Avoid hostility. The whole point of Fair Observer is openness to different perspectives from perspectives from around the world.

2. Comment Thoughtfully: Please be relevant and constructive. We do not allow personal attacks, disinformation or trolling. We will remove hate speech or incitement.

3. Contribute Usefully: Add something of value — a point of view, an argument, a personal experience or a relevant link if you are citing statistics and key facts.

Please agree to the guidelines before proceeding.