Our Devil’s Dictionary habitually traces the use or misuse of English terms or expressions that occur as public personalities or journalists comment on current events. Exceptionally today we feature a word that does not belong to the English language. It merits our consideration because it appeared, though delivered with an erroneous pronunciation, in some pertinent analysis prominent American military strategist, retired Colonel Douglas MacGregor provided concerning the regional impact of the Israel-Hamas.

Macgregor can be forgiven for misremembering a foreign word that happens to be exotic in its spelling as well as pronunciation. He is absolutely right about the source of the concept behind the word: the influential 14th century Arabic philosopher, Ibn Khaldun, remembered as the pioneer of a non-religious philosophy of history.

Macgregor tells us that the term proposed by Khaldun is “a word you don’t hear much anymore.” I’m not sure it has often been heard in the past. The erudite colonel is probably thinking about an unfortunate trend among modern theorists of international relations, especially those active in making and enforcing policy in the geopolitical sphere. Even among intellectuals, history – its lessons and its deepest insights – has suffered from serious neglect. The thinking of political thought leaders today is shaped by principles drawn from the fields of engineering, statistics and contemporary management strategies.

Col. Macgregor defines Ibn Khaldun’s 600-year-old concept as signifying “social cohesion, group solidarity or unity of action.” In English there is no single word to encompass its meaning. Stepping away from an idea that is so foreign to Western thinking that we need a string of concepts to account for its range of meanings, our definition of the day offers a slightly different take.

Today’s Weekly Devil’s Dictionary definition:

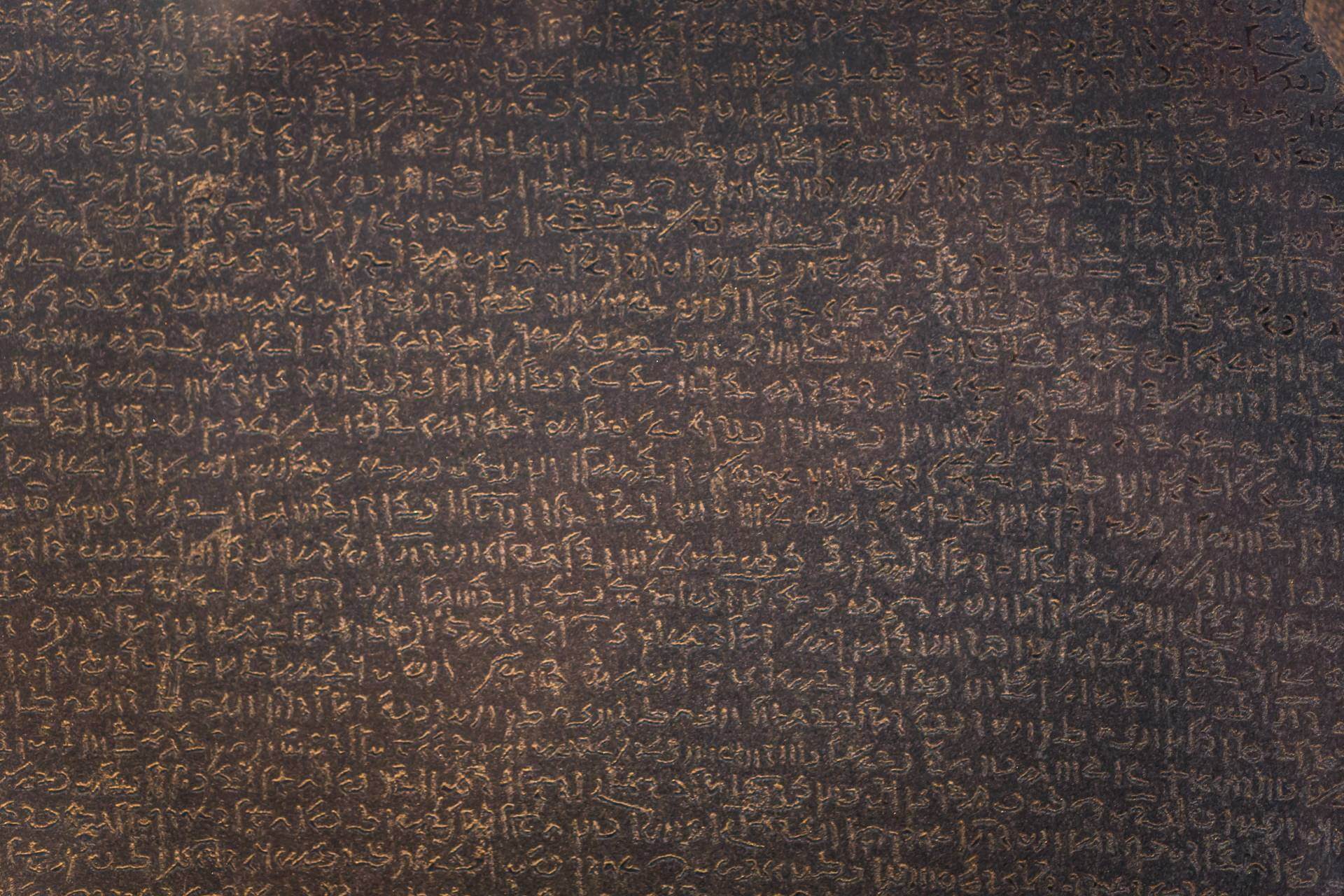

Asabiyya:

A word that does not exist in the English language and therefore a concept that does not exist in the language, but which, if it did, would explain what English speakers fail to understand about much of the world.

Contextual note

In Edward T Hall’s seminal book Beyond Culture (1976), the American anthropologist and founding father of the area of study we call intercultural communication explains that “the future depends on man’s being able to transcend the limits of individual cultures. To do so, however, he must first recognise and accept the multiple hidden dimensions of unconscious culture, because every culture has its own hidden, unique form of unconscious culture.”

Hall theorizes a distinction between what he calls high and low context cultures. High context cultures embrace values that emerge from relationships. Low context cultures give priority to formal rules and laws. For anthropologists such as Hall, the US appears as a model of low context culture in which rules and the strictures of law dominate, clearly superseding the effect of relationships.

Most of the rest of the world, from Latin America to Africa and Asia, sees rules of behavior as useful guidelines, but clearly subordinate to the quality and consistency of relationships. That very fact may clarify the phenomenon so visible in today’s geopolitics: the failure of the US to convince the rest of the world to respect what it promotes as the “rules-based international order.” Rules are fine but they can lead to the kind of endless and fruitless bickering that now characterizes all public political debate in the US.

Ibn Khadun’s concept of asabiyya derives from the tribal psychology that exists locally in all human societies. Tribal reality is almost always high context, though more complex groupings emerge that may tend in one direction or the other. In their book Dawn of Everything David Graeber and David Wengrow describe the relationship between two neighboring North American societies – the Kwakiutl and the Yuroks – whose cultures were in sharp contrast, the first high context (hierarchical) and second low context (egalitarian). In Europe, following the Reformation, Catholic countries retained their high context culture, rooted in historical tradition, compared to Protestant countries that evolved towards cultural (though not necessarily political) egalitarianism. Protestant cultures increasingly substituted the force of law for the bond of relationships as an overriding principle of government.

Related Reading

Khaldun understood that the geographical reach of Islam established over the previous seven centuries had created the conditions for a widely shared high context culture. The philosopher and historian realized that the force of asabiyya required a referential framework, in this case the Islamic teachings, but it took its meaning from the act of shared experience rather than from any set of doctrines. Christian Europe during the Middle Ages had its own asabiyya, a factor that contributed to the sense of mission underpinning the Crusades. The prolonged conflict between the two in the Middle East led to the weakening of both and eventually the evolution of Western Christian culture into its modern low context version.

Historical note

When Edward Hall invoked “unconscious culture,” he was referring to the complex heritage embodied in the historical memory of a particular group of people. When he speaks of the need to transcend individual cultures, he does not mean abolishing or ignoring them. Instead, he sees the anthropologist’s need to seek universals that are not inconsistent with the experience and accumulated worldview of those groups. Khaldun’s asabiyya stands as an example of this effort of transcending to understand how cultures function, despite the differences in their traditions, narratives and scriptures.

One of the major errors great and even lesser powers have always made has been neglecting the force of asabiyya and the way it may contradict and undermine even the most seemingly rational rules. The error consists in believing that transcending individual cultures means overcoming and abolishing their existing traditions and replacing them with something else, or in some cases nothing at all. This sums up the reasoning of Europeans during the Crusades that reemerged in the race for colonial conquest driven by the “civilizing mission” of enlightened Westerners. It reappeared more recently with the post World War II “rules-based order.”

Those three periods, which saw Western cultures seeking to transform entire regions of the world, reflected three different types of assault on the cultures they targeted. The Crusaders found their justification in religious doctrine; the colonialists in economic interest combined with a “civilizing” religious pretext; and the “rules enforcers” through a combination of economic interest and the ideology of progress.

Today, in the 21st century, the trend of dismissing what some appear to think of as the excess weight of history has produced a trend highly visible in the US: the dismissal of history itself as an uncomprehending intellectual elite’s unproductive obsession with the past.

Many thinkers and commentators want us to believe that we live in a world that is fundamentally different from anything that existed in the past. Our acceptance of globalization as a new historical norm means that we see the world defined not by the people who inhabit it, but by the economy of the nations those people live in. Technology defines the environment that sustains us.

We measure the health of the economy itself by one criterion: growth. Technology encapsulates and symbolizes the enshrinement of “progress” as a dominant cultural value, redefining ethics as the study of the means of achieving comfort and convenience.

For cognitive scientist Steven Pinker, the meaning of history is summed up in the measurable statistical progress visible in the trends that have liberated individuals from the material constraints. A younger generation of futurist “thinkers” such as Ray Kurzweil, Nick Bolstrom or Elon Musk, predict, with an air of omniscient authority, how humans will live in the coming decades and centuries.

For these thinkers, history is a collection of failed practices that can provide no guidance on that question. Only those brilliant minds, who infallibly understand technology, can help us to understand what they see as an established truth: that human nature now must align with technological progress.

Douglas Macgregor reminds us that Ibn Khaldun’s understanding of historical processes may still be at work even in the age of AI. This should help us reflect on who we were in the past, who we are now, and who we should try to become.

*[In the age of Oscar Wilde and Mark Twain, another American wit, the journalist Ambrose Bierce produced a series of satirical definitions of commonly used terms, throwing light on their hidden meanings in real discourse. Bierce eventually collected and published them as a book, The Devil’s Dictionary, in 1911. We have shamelessly appropriated his title in the interest of continuing his wholesome pedagogical effort to enlighten generations of readers of the news. Read more of Fair Observer Devil’s Dictionary.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.