What can the young people of today learn from Yeats’ poetry?

“That is no country for old men. The young / In one another’s arms, birds in the trees / — Those dying generations — at their song, / The salmon-falls, the mackerel-crowded seas, /Fish, flesh, or fowl, commend all summer long / Whatever is begotten, born, and dies. / Caught in that sensual music all neglect / Monuments of unageing intellect.”

Thus wrote William Butler Yeats (1865-1939) when he was 62—a sort of a complaint, perforce, as he was growing old.

Today, things haven’t truly changed. So much so we could conjure up images of such Yeatsian similes or metaphors. Like the abundant sexuality of our young populace, the profusion of city folks, the neurosis in our society—“whatever is begotten, born, and dies.” Agreed that the great Irishman was ageing but, in reality, the dissimilitude between sexuality and the ageless was always a fundamental component in his thought since a young age—in heart and spirit. One that is akin to India, or the world, of our age.

Monuments of Intellect

Yeats’ idea of sensual music was, likewise, something that more than meets the eye, or the ear, or even conventional thought and wisdom. It is an extremely disturbing aspect of what is often forgotten in the reckless quest of sexuality. So also his “monuments” of the word “intellect.”

Yeats does not, of course, relate to practical intellect—the reasoning power of the scientist. What he tries to connect is the spiritual intellect—the intellect of Dante’s Divine Comedy, or in the eastern context, the intellect of great seers and saints like Confucius, Lao-Tzu, Sankaracárya, Ramanujacárya, Madhvacárya, Chaitanya or Kabir. This is also the intellect of the Buddha, Plato, Plotinus, St. Patrick, St. Paul and Rumi, in another context: of what the spiritual intellect creates does not die. It is something that is imperishable. Or simply permanent.

Yeats never believed in the language of the absolute vis-à-vis sensuality and spiritual intellect. He thought of the two parallels as day and night, and vice versa. He often talked of what is so easily forgotten in different cultures, East or West. Yeats’ spiritual intelligence was based on sensuality, on which everything else rests. Be that as it may, in the India of today, or any other milieu, not many would care about the afterlife.

As one perceptive writer remarked jocularly, “Now that no one believes in the afterlife, everyone writes.”

Vertical Thought

The inference is obvious. Many of our attempts have been geared to create immortality without the help of the immortals, because most of our forebears lived in simple communities, although they built enormous, permanent mansions, or nectars in stone, for the gods. Today, we seem to build such “castles” for politicians and financial wizards.

There’s an old belief that says that whenever one makes a decision, one should think of its effect down to the 7th or 8th generation. This may, quite neatly, be linked to Yeatsian reflection. Or what is called vertical thought. Of a positive effect in a chaotic world that is also planet Earth’s endowment in the new millennium. Vertical thought is just the opposite of what would often be a decision based on short-term profits—in other words, a refusal to invest in the unit, or people who work in it.

As Mahatma Gandhi demonstrated, the most he could say of his life was that he was steadfast in his commitment to understanding truth and helping make it manifest in the world.

In vertical thought, there’s no disparity between men and women. Because one automatically becomes wiser when one learns to think vertically. As a matter of fact, vertical art is quite similar to imagining the patterns of water flowing under your feet—of ogres exploding out of Earth’s waters and rising into the clouds. It’s also something similar to the vast distances between the stars.

Today, more than any time before, we are all struggling with moral questions too. They are also moral dilemmas that not only define how we live, but directly affect other people’s lives. Moral questions, in any age, past or present, are often difficult. They often involve risk and daring. They can lead to discomfort, just as much as they can lead to the deepest kind of comfort when you feel that you are an upright person, a person of integrity, not a wily politician.

New Age Diet

In the modern world, such decisions involve specific situations: spending more time at home, or work, mustering the courage to oppose conflicts— environmental and social issues, or human rights in society—or, keeping silent. Put simply, moral life is a constant backdrop in our personal and social lives. Its implications may call us to comply with or defy cultural parameters, or even definitions. It is, therefore, lived in the particular, and in the imminent challenges of our everyday lives.

The decisions in today’s framework call upon personal qualities like courage, responsibility, empathy, humor, integrity and generosity. Words full of meaning, yes, but totally neglected where they matter most. Yet one primal fact remains: They are often tested through moral action. While it’s agreed that it is possible for one to have a general set of guiding moral principles, the practical implications of thought and action are not served well through an overly simplistic attitude, or black-and-white approach to morality.

We live at a time when moral questions are being raised with a great sense of urgency. We have a long way to go in achieving moral integrity as a society and as citizens in it. More so in the present dispensation, where more and more youngsters are being brought up by the all-pervading, surrogate mother called television, the New Age diet—call it what you may. On the bright side, as has been history’s theme song, human struggle between self-interest and human interest is forever inspired by the imaginations of the intellect—by our artists, and our imaginations.

Yet the equation isn’t as simplistic. Our imaginations today are occupied by fear and culpability. The results, therefore, have been devastating. Yet there’s hope. When human beings are informed by love that is spiritual, dutiful or secular, it envelops reverence for all living things. When we reach such a plateau, our imaginations become the driving force of moral action, not otherwise.

Yeats’ idea of sensual music was, likewise, something that more than meets the eye, or the ear, or even conventional thought and wisdom. It is an extremely disturbing aspect of what is often forgotten in the reckless quest of sexuality.

To return to Yeats again—in the aftermath of every political, racial, ethnical, religious, militant, terrorist, sectarian, or geographical, imbroglio—his meditations on the horrors of war and the need for healing in morally uncertain times are as relevant today than ever before.

Seamus Heaney (1939-2013), another great Irishman, called Yeats’ work “necessary poetry.” “Yeats,” he said, “touches the (very) base of our sympathetic nature while taking in at the same time the unsympathetic reality of the world to which (that) nature is constantly exposed … to remind us that we are hunters and gatherers of values, that our very solitudes and distresses are creditable, in so far as they too are an earnest of our veritable human being.”

The deepest and most personal moral concerns today coincide with the expanding chapter of profound moral reassessment in our society. We are in conflict about what we expect of our young and our old, what we expect of employers and employees, how we assess rights and responsibilities, and how we value the lives of the poor and the otherwise needy. It is surely a moral failing.

The task is difficult, but not impossible. As Mahatma Gandhi demonstrated, the most he could say of his life was that he was steadfast in his commitment to understanding truth and helping make it manifest in the world. It is a perfect call to reassembling what has been scattered in India, or the globe, of our age, and beyond. It is also something that tells us not about just being right, but about being awake, as Yeats outlined, and wakeful to suffering around us and aiming to reduce it, not add to it.

It is a formidable formula because the complexity of contemporary life does not yield itself to elementary formulaic solutions. More so because we live in our imaginations. In other words, the ideas we unravel can free or imprison us. How we approach such ideas and how we act would, therefore, define who we are, and what kind of society we live in. In the words of Robert Browning (1812-1889), the great English poet and playwright: “The common problem, yours, mine, everyone’s / Is—not to fancy what were fair in life / Provided it could be — but finding first / What maybe, then find how to make it fair / Up to our means.”

The onus is on us all—a clarion call that seeks ways to reaffirm our faith in our ability to live in harmony with ourselves, with each other, and Mother Earth. It’s a simile Yeats would have certainly acquiesced to.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

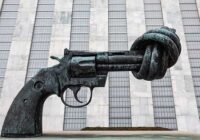

Photo Credit: Fulcanelli / Shutterstock.com

We bring you perspectives from around the world. Help us to inform and educate. Your donation is tax-deductible. Join over 400 people to become a donor or you could choose to be a sponsor.

We bring you perspectives from around the world. Help us to inform and educate. Your donation is tax-deductible. Join over 400 people to become a donor or you could choose to be a sponsor.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.