Many of the issues Muhammad Ali brought to the fore are still here, some in aggravated form.

An enigmatic American cultural icon disappeared this week, for the fourth and final time. Muhammad Ali is now routinely called by the media “the greatest sportsman of the 20th century,” but his iconic status had much more to do with one of the bitterest and still unresolved moments of American history than with athletic accomplishment.

Ali, the defiant draft-dodger, encapsulated the complex reality of psychedelic ‘60s, remembered as an epoch of artistic innovation, rebellion, anti-authority protest, transformation, liberation and unbridled expression. Cassius Clay emerged in 1960 as a graceful innovator in the techniques and style of boxing, quickly gained a reputation as a rebel against the manners of the age, morphed into a daring voice of protest, helped transform the notion of patriotism and justice, had a serious impact as a liberator of his race and by the end of the decade established himself a wildly creative entertainer. He left a lasting impact on Americans’ perception of themselves and their culture.

It was a time of cultural and political anguish and confusion punctuated by the promise of Camelot, the tidal wave of civil rights activism and the brutal backlash against it, the assassination of a president, the headlong rush into America’s first serious neo-colonial war and its progressive escalation, the spontaneous emergence of hippies and then yippies alongside Black Power and the militant feminism.

Cassius Clay started it off as a talented athlete with a flair for absurdly comedic public relations. His story over that decade was one of easy success on the road to the heavyweight championship followed by a deeply agonistic struggle in the social and political sphere that called into question American values concerning race and militarism. When the butterfly Muhammad Ali emerged from Cassius Clay’s cocoon in 1964, he was worse than a troublemaker. When he refused conscription, he was branded as the enemy of everything America stood for.

After winning an Olympics gold medal in 1960, Cassius Clay put in action his apparently conscious plan to become the most hated young man in sports, hated for his manner and hated for promoting his race.

The construction of the comforting image we now have of Muhammad Ali on the Mount Rushmore of American sports and as a paragon of individual moral conscience was consolidated for the first time only after the confusion of the ‘60s had given way to disillusioned conformity of the ‘70s and then transformed again after his retirement from boxing, allowing him to become a symbol of the hypocrisy he had once challenged. The myth has dethroned the man and his contribution to his times. His final departure of the man behind the myth—the fourth disappearance of his lifetime—should give us the opportunity to set the record straight.

Creating the Persona

Let’s go back to the beginning—the launch of Cassius Clay, winner of the Olympic gold medal and future contender for the heavyweight championship. To be a contender you need to promote yourself or be promoted. Most boxers worked with their footwork and fists alone and left promotion to the professionals. Clay was different. He had the talent, if not the science, of promotion. Combined with his exceptional skills as a boxer and his flair for innovation, he created an enduring image that the media could not ignore.

An odd parallel could be made between young Cassius Clay in 1960 and Donald Trump in 2016. The young boxer built his own image, used the force of the media and a talent for provocation as well as prevarication to sell it. He possessed and even cultivated an elevated level of self-esteem. And in spite of a very negative—but deliberately provoked—initial reception by the sports establishment, Cassius ensured that he would be noticed.

This was the first step in the long and complex process that would ultimately turn him into a fixture of US culture. Ali’s achievement, unlike Trump’s, was already more complex because based on authentic talent and skills. It would become more complex when the dramatic events of political, social and cultural history became part of Ali’s story.

Today, Ali is revered as a model of personal achievement, a symbol of personal integrity. He is honored as a self-made black man who single-handedly proved his worth, successfully battling his way to the top. He has thus become the incarnation of the myth at the heart of US culture, the heroic individual who achieved success through self-reliance and self-creation.

But that wasn’t how the story played out at the time. After winning an Olympics gold medal in 1960, Cassius Clay put in action his apparently conscious plan to become the most hated young man in sports, hated for his manner and hated for promoting his race. According to the codes of the time, “darkies” weren’t supposed to self-promote, neither themselves nor their race. Protesting flagrant injustice, as Martin Luther King, Jr., had begun doing, was barely tolerable. Drawing attention to the beauty and culture of their race was a clear breach of good manners.

Cassius Clay was branded as a brash verbal bully, an impertinent black kid with fast hands who after his success among the amateurs in the Olympics would, without the slightest doubt, promptly get thrashed by any one of the brutal professionals he would soon face. All the pundits, experts and amateur commentators at the time expected Clay to get a quick comeuppance, if not at the hands of seasoned heavyweight ex-champions or contenders, like Floyd Patterson or Archie Moore, then surely from the unbeatable reigning champion Sonny Liston. The influential sports journalist Murray Kempton summed it up for the majority with this comment: “Liston used to be a hoodlum; now he is our cop; he was the big Negro we pay to keep sassy Negroes in line.” When the bout with Liston actually did take place in February 1964, Cassius Clay was a 7-to-1 underdog.

Grace and speed had overcome strength. The juvenile delinquent had schooled the cop. After that fight it became impossible to ignore the young boxer or dismiss him as a pretender, though some claimed at the time that the fight was fixed. But the new champion subsequently shook up the media even more than he had shaken up Liston after six rounds. Only a few days later he shocked the world when he announced that he was abandoning his “slave name” Cassius Clay in favor of his new Muslim name, Muhammad Ali.

Worse, he let it be known that he had formally adhered to the reviled religion of Elijah Muhammad’s Nation of Islam, aka Black Muslims, considered to be an extremist cult. The media had no idea how to react. Journalists couldn’t decide whether to cheer for the new champion and forgive him his bad manners, condemn him for joining a terrorist cell or hope that in a rematch Liston would prematurely terminate his career. What few Americans who hadn’t lived through that era realize today is that from that moment on, Ali—today’s legend—was authentically vilified by most of the white establishment and universally condemned by the media. Even African-Americans didn’t know what to think of him. How would this provocation affect the cause of civil rights?

Six months earlier, in August 1963, Martin Luther King had made history with his “I have a dream” speech in Washington. At the very moment when Dr. King—in spite of being himself perceived as an agitator in an age of extreme conformity zealously enforced by J. Edgar Hoover—was beginning to be accepted by white society thanks to his eloquent rhetoric and his “turn the other cheek” Christian stance, the Nation of Islam was seen as an existential threat to the American establishment, liberal and conservative alike. Southerners hated them because they were black. Northern liberals were embarrassed because they rejected their solution of tolerance and gradual integration. Dr. King still called his people “negroes” whereas the Black Muslims and the emerging Black Panthers—preaching armed revolution in the face of institutional racism—had already banished a word that sounded too close to the supreme racist epithet, “nigger.” “Are you afraid to call us black?” was the challenge both groups sent to the “ofays” and “gray boys” in the south and north alike, who proudly called themselves “white.”

For several years, only one prominent member of the sporting press, Howard Cosell, refused to call Ali by his “slave name,” Cassius Clay. Those of us teenagers who not only thrilled at Ali’s ballet-like boxing skills and hungered to see him “float like a butterfly and sting like a bee,” but who also had serious misgivings about the racial climate in the US, couldn’t help admiring Cosell’s courage as a journalist who had the guts to take Ali on his own terms, both as a boxer and a man of conscience. Already in 1964 the battle around Ali was engaged: The political and media establishment and the majority of the population of the United States concurred in branding Ali an unwanted alien. But Muhammad Ali, the iconic hero of moral and political conscience, was still waiting to be born.

I speak for the poor of America

Everything changed when in March 1966 Ali refused to step forward for the draft and accepted the promised consequences, jail time and loss of his professional status, including the coveted and quasi-mythic title “heavyweight champion of the world.” At the time, the media calmly pointed out that Ali should simply accept conscription because, as a sporting celebrity, he would have a cushy time, could continue training and would be programmed to fight exhibition matches organized by the military. It wouldn’t be any worse than Elvis’s two years of service. Any self-respecting American—patriot or not—would have accepted that.

But Ali wasn’t concerned with his own comfort. He was ready to challenge the very order of things. He felt he could not back down. He framed his refusal in the terms of an oppressed black man from the south being given incomprehensible orders by a white establishment that only needed him as cannon fodder. But his message of resistance resonated with the younger generation, who were equally called upon to go off and fight a brutal war in a distant land, conducted by a president who took office thanks to the shocking assassination of a popular young president. Here is how Ali framed it:

“My conscience won’t let me go shoot my brother, or some darker people, or some poor hungry people in the mud for big powerful America. And shoot them for what? They never called me nigger, they never lynched me, they didn’t put no dogs on me, they didn’t rob me of my nationality, rape or kill my mother and father … How can I shoot them poor people? Just take me to jail.”

Ali had officially proclaimed himself a deserter, a criminal. But the implication went further. His position wasn’t just that of an opponent of the war who didn’t want to serve, a position the establishment could understand but obviously not tolerate. Ali’s position was that of a declared enemy of US foreign policy. He spoke from the point of view of the oppressed. And, possibly unwittingly, he was among the first to dare formulate and highlight the link between racial oppression in the US and imperialistic militarism against foreign, non-European populations.

I say “unwittingly” because Ali was never a deep thinker and never pretended to be one, to his dying day. In that sense, the braggadocio always remained humble. It’s worth noting that within a year MLK may have taken the hint from Ali to articulate the link between racist practices in the US and its foreign policy. Here is King:

“Somehow this madness must cease. We must stop now. I speak as a child of God and brother to the suffering poor of Vietnam. I speak for those whose land is being laid waste, whose homes are being destroyed, whose culture is being subverted. I speak for the poor of America who are paying the double price of smashed hopes at home and death and corruption in Vietnam. I speak as a citizen of the world, for the world as it stands aghast at the path we have taken. I speak as an American to the leaders of my own nation. The great initiative in this war is ours. The initiative to stop it must be ours.”

King went on to develop the link even further when he told his staff in 1967:

“We must recognize that we can’t solve our problem now until there is a radical redistribution of economic and political power… this means a revolution of values and other things. We must see now that the evils of racism, economic exploitation and militarism are all tied together… you can’t really get rid of one without getting rid of the others… the whole structure of American life must be changed. America is a hypocritical nation and [we] must put [our] own house in order.”

Shortly after that, in April 1968, Martin Luther King, Jr., was assassinated. The same mystery surrounds this event as the assassinations of JFK in 1963 and of his brother Robert in June 1968. The “house” King referred to clearly was not “in order,” and one of the methods for reinforcing the existing order now appeared to be well-planned and equally well-masqueraded mafia-style elimination.

Although clear evidence of conspiracy in all three assassinations actually does exist, each of these three murders is still officially described in history books and the media as a tragic, isolated incident perpetrated by a lone gunman. What is important to retain, however, is that the suspicion that well-organized foul play was involved has remained in the American psyche even after decades of hiding the evidence and airbrushing the facts. The public perception of this series of high-profile assassinations has contributed significantly to distrust of the federal government on both sides of the political spectrum.

Had Dr. King pushed his analysis too far for his own good? Was he treading on forbidden ground? For J. Edgar Hoover and the other masters of national security, black activists, just like lobbyists, may be tolerated so long as they remain focused on their specific agenda. US culture encourages specialization for everyone, and for minorities in particular. Systemic thinkers who make embarrassing or unsettling links between disparate domains will always be suspect, particularly when they demonstrate not just the negative effects of the institutions but how the system actually produces those effects.

The marginalized rebel was becoming increasingly familiar with the establishment, enjoying the limelight, accepting his role as a star among the beautiful people. He was careful to protect his image as “the greatest” while at the same time never betraying—though sometimes forgetting—his fundamental moral choices.

It may well be that, as many claim, Muhammad Ali directly inspired Dr. King’s critical positions on foreign policy. But as a public performer and an increasingly visible personality, Ali—still allied with the Nation of Islam—didn’t attempt to join forces with King or follow his lead by attempting to develop and promote a coherent line of thought permitting to understand the system he was at odds with. Ali was still a boxer, though without a license. He continued to fight for his two privileged causes, racial justice and respect for the Muslim religion, without seeking to articulate the links between them or calling into question the economic and political system that actually explained how they were connected.

Ali was of course always more than a boxer but he clearly was never a thinker. He was too spontaneous, too much a performer. As Norman Mailer loved to point out, Ali was a brilliant talker. His talking, his provocative formulations, could inspire thinking in others. Ali’s talents were indeed varied: He was first of all an artist of the ring, an innovator in his sport, but for the consumer public he was also a grating wit, a master of spontaneous verbal acrobatics that were both socially targeted and fun. There’s even a good case to be made for considering Ali as the originator or, at the very least, a key inspirer of the genre of rap and hip-hop.

Second disappearance: from active boxer to living legend

But three and a half years of forced retirement and age had taken its toll. With his diminishing speed and agility—the key characteristics of his original style—Ali’s boxing career ended in predictable failure after lasting far longer than a concern for his future well-being should have permitted. His dexterity waned, he took a few too many punches, his health was compromised and his mental faculties diminished or perhaps seriously impaired. Ultimately he lost his voice as well.

That was worse than losing his speed. The Louisville Lip, as he was called at the beginning of his career, had lost his tongue. The decline was rapid. Curiously, it paralleled a similar contradictory trajectory of US political history at the end of the 20th century. The verbose ‘60s had given way to the taciturn ‘70s. Nixon’s retreat from Vietnam ended the decade-long bitter, seriously engaged debate about unjust wars, which had put ethics on the table as a national issue. Watergate provided a different kind of ethical distraction, focused on petty skullduggery, cover-up and the good old American preoccupation with the only original sin—lying. Remember George Washington and the cherry tree? Then came the Reagan years when American politics was put to sleep.

By the time Ronald Reagan was elected in 1980, after a decade that saw the retreat from Saigon and Nixon’s resignation, what was considered the natural default position of US ideology returned: Any war we choose to engage in must be, by definition, a just war. Vietnam had thrown some doubt on this doctrine, but order was now reestablished and it has miraculously persisted right through Barack Obama.

Ali’s struggle of the ‘60s had already lost all meaning, partly because he no longer needed to worry about it once he was able to reprise his boxing career and even regain the championship. Just as abolishing the draft and instituting a volunteer military permitted Nixon to defuse the anger and anguish of the young, who could then calmly plot out their future.

Those issues buried, Ali no longer had even a symbolic role to play with regard to foreign policy. To the extent that his life was no longer affected either by Washington’s politics or the provocative doctrines of the Nation of Islam, Ali’s public persona was comfortably contained within that of the comeback boxing hero, who continued to preach for the African-American cause but without shaking the walls of the house. He even managed the public relations coup of winning back his title not in Las Vegas but in Africa, which had its symbolic importance, albeit in the home of the corrupt Mobutu rather than that of the principled Patrice Lumumba, a victim of CIA meddling in the 1960s.

Ali’s skill as a cultural observer of racial issues nevertheless came to the fore on occasion, as in this lucid analysis of the Rocky phenomenon: “I have been so great in boxing they had to create an image like Rocky, a white image on the screen, to counteract my image in the ring. America has to have its white images, no matter where it gets them. Jesus, Wonder Woman, Tarzan and Rocky.”

But thanks to his success story—always a key to redemption in US culture—Ali himself had become a celebrity with a positive image for the white population. The marginalized rebel was becoming increasingly familiar with the establishment, enjoying the limelight, accepting his role as a star among the beautiful people. He was careful to protect his image as “the greatest” while at the same time never betraying—though sometimes forgetting—his fundamental moral choices.

But he clearly let himself be tempted by some of the comforts of being seen as a pillar of the white establishment. In 1977 he participated in Hollywood’s annual narcissistic ritual of self-celebration, playing out a scripted comedy sketch with Sylvester Stallone at the Oscars. On that occasion, Stallone called Ali “a 100% certified legend,” signifying that Ali the rebel and protester had definitively gone into retirement.

Ali nevertheless always remained committed to his two fundamental principles, which had morphed from a political orientation to a purely cultural one. The themes that moved him were racial justice and religious identity. His departure from boxing and his physical disabilities took him away from any permanent public platform, but his status as a revered legend meant that the public would be curious about, if not attentive to, his declared positions on public issues.

In 1984 the cause of racial justice led him to back the unsuccessful presidential aspirations of Jesse Jackson. Jackson represented black hopes for expanded civil rights but, most of all, recognition black assertiveness. But when Jackson’s campaign failed, Ali surprised everyone by endorsing Reagan. This time it was Ali’s second cause, religious integrity, that guided him. He needed only one simple reason: “He’s keeping God in schools and that’s enough!” The contradiction was flagrant. Why would the man sacrifice the prime of his career to oppose Johnson’s Vietnam policies and American militarism turn around and support an openly militaristic president, who at the same time was fueling a brutal war against Ali’s Shiite brethren in Iran as well as promoting American imperialism in Latin America and other places?

Through his deep Muslim faith Ali ignored all other differences, the real political issues, and apparently found an affinity with the party that identified with religious fundamentalism, albeit Christian and American. At the same time, Ali had already definitively repudiated the Nation of Islam (with its Shiite orientation) having converted to Sunni Islam. His decisions with regard to public issues, as always, were guided by his personal preoccupations and emotions, which is not to say his calculated self-interest. Ali remained committed to the ideals and humanitarian goals that had underpinned his objection 20 years earlier to being an instrument of death for Vietnamese peasants. He simply hadn’t made the links that Dr. King had made.

Ali’s third disappearance: the voice that went silent

It was nevertheless sad to see his gradual transformation into a docile icon of the poorly-framed and often disastrously-applied ideals and proclaimed “good intentions” of the US government. He never endorsed them but he seemed to accept the reigning order. It is difficult for an observer to escape the impression that the brash, headstrong young man who had defied a nation at war had become a complacent, though in all probability unwitting, accomplice of the very military-industrial complex that had drafted him for service in Vietnam.

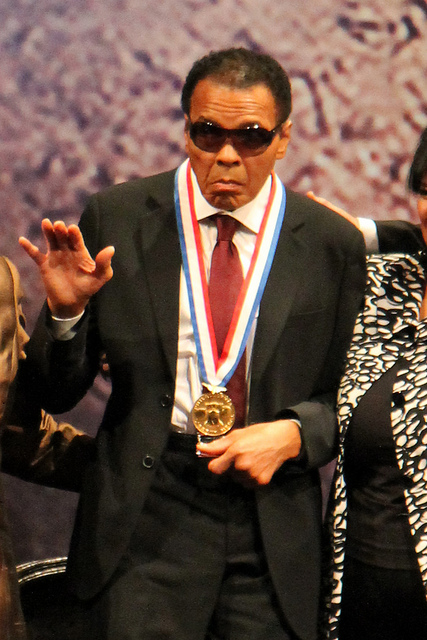

Ali Receiving the 2012 Liberty Medal © Flickr

This was never clearer than when in 2005, alongside Alan Greenspan, he accepted the Presidential Medal of Freedom award from George W. Bush. The rapid decline of Ali’s health had by that time taken away his voice. He was reduced to the ritual of miming in public the silent persona of the man of integrity and conscience on the very stage of the imperial regime against which he had rebelled. It certainly wasn’t his intention but the effect was as obvious as it was sad. What would MLK have thought of an award granted by a president and a regime considered by many to be war criminals, an award received in the company of one of the greatest promoters of unbridled capitalism, Alan Greenspan?

Muhammad Ali, Martin Luther King, Jr., and even Nelson Mandela—each of them considered enemies of the state in the eras of J. Edgar Hoover, Nixon and Reagan—have all been turned, deliberately and cleverly, into icons that could be absorbed into the American mythos, their contradictions, their challenges to the system and its culture effaced. Ali and King were both highly vocal black men, strong personalities engaged in serious actions of civil disobedience, mistreated by the prevailing laws, martyrs of the system. By being turned into legends they have been made to appear as pillars of the system that formerly pilloried them. It is what the French call récupération—the system’s method of neutralizing a threat by making it appear to be a vital part of the system itself, thereby justifying the system. It may be that because he no longer had a sustainable voice or because he remained solely focused only on the specific causes that were dear to him Ali allowed himself to be “recuperated.” It is highly unlikely that he chose to do so.

History and myth

The public mythology we persist in being told is our “history” is a force powerfully managed by our media. Most of the public eulogies of Muhammad Ali have skirted the true history and painted a heavily airbrushed legend in its place. Here, for example, is President Obama’s sentimental tribute to the passing of Muhammad Ali:

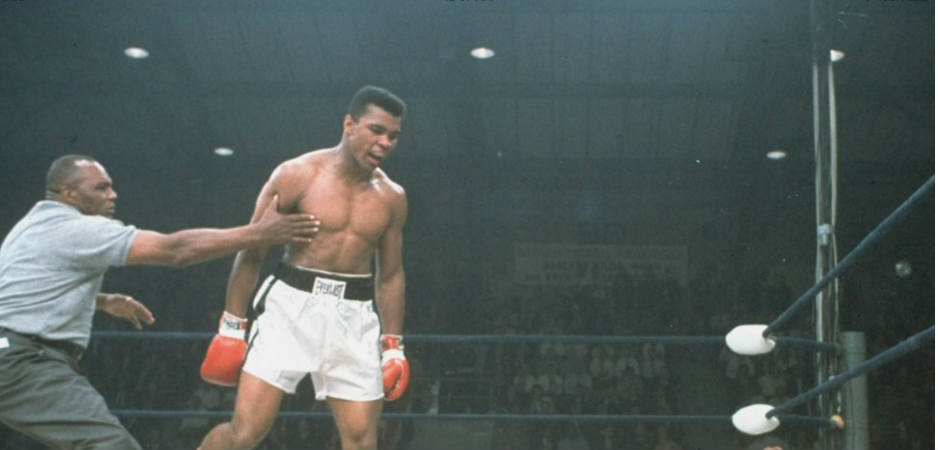

“In my private study, just off the Oval Office, I keep a pair of his gloves on display, just under that iconic photograph of him—the young champ, just 22 years old, roaring like a lion over a fallen Sonny Liston. I was too young when it was taken to understand who he was—still Cassius Clay, already an Olympic Gold Medal winner, yet to set out on a spiritual journey that would lead him to his Muslim faith, exile him at the peak of his power, and set the stage for his return to greatness with a name as familiar to the downtrodden in the slums of Southeast Asia and the villages of Africa as it was to cheering crowds in Madison Square Garden.

‘I am America,’ he once declared. ‘I am the part you won’t recognize. But get used to me—black, confident, cocky; my name, not yours; my religion, not yours; my goals, my own. Get used to me.’”

The president hadn’t studied or misremembered his history. Obama’s account of the “iconic photograph” is factually wrong. The photograph he is referring to was of Ali’s rematch with Liston nearly a year and a half after winning the championship at the age of 22. Ali officially converted to Islam and changed his name in the immediate aftermath of the first bout. The man in the picture was not Cassius Clay but Muhammad Ali.

Obama chooses selectively to “remember” the Olympic Gold Medal (patriotic glory) and paradoxically refers to “exile,” whereas Ali was deprived of the privilege of exile when the government took his passport away, effectively preventing him from earning a living anywhere in the world.

What Obama refers to as Ali’s “spiritual journey” wasn’t a simple voyage of self-discovery but a political and social struggle, for Ali himself but more significantly for his race and for justice itself. It was a struggle that exploded dramatically and chaotically in the riots of Los Angeles, Detroit and so many other inner cities through the rest of the decade. Reducing that to one man’s “spiritual journey” is a clear case of historical revision.

Obama chooses selectively to “remember” the Olympic Gold Medal (patriotic glory) and paradoxically refers to “exile,” whereas Ali was deprived of the privilege of exile when the government took his passport away, effectively preventing him from earning a living anywhere in the world.

The quote Obama cites at the end is authentic but, when spoken by Ali in 1970 in the context of his trial as a draft dodger, it was launched as an aggressive challenge, an act of defiance, a brutal calling into question of traditional white American identity. Taken out of its historical context, Obama makes it sound like an excerpt from an inspirational speech given by one of America’s self-made successful entrepreneurs, not of a man humiliated and brutalized by a bellicose government.

Muhammad Ali accomplished many things. He gave us authentic thrills and moments of sublime beauty in the ring. He pulled away the veil on race relations and foreign policy at a time when the military-industrial system had begun arrogating every form of power, from military force to personal intimidation, just as Dwight Eisenhower warned in the very year Cassius Clay won his gold medal. Just as other not quite silenced voices—such as Edward Snowden’s—are still reminding us today. Ali’s boxing career and the deleterious effects it had on his health sadly set him on a different path preventing him from following through in his later years.

Fifty years ago Muhammed Ali was constantly in the news, sparring with his fists, his wit and his conscience in the name of causes the American public couldn’t yet understand. His contribution was immense, much greater than what the “legend of Muhammad Ali” we have since been fed will ever allow us to understand. Many of the issues he dealt with are still here, some in aggravated form. The voice of Ali of yore and that of Martin Luther King, Jr., and Malcolm X still contain lessons we need to go back to their historical context to learn from.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Photo Credit: H. Michael Karshis / Peter T. / Flickr

We bring you perspectives from around the world. Help us to inform and educate. Your donation is tax-deductible. Join over 400 people to become a donor or you could choose to be a sponsor.

We bring you perspectives from around the world. Help us to inform and educate. Your donation is tax-deductible. Join over 400 people to become a donor or you could choose to be a sponsor.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.