We are social beings who need close supportive contact with others for both psychological and physical health.

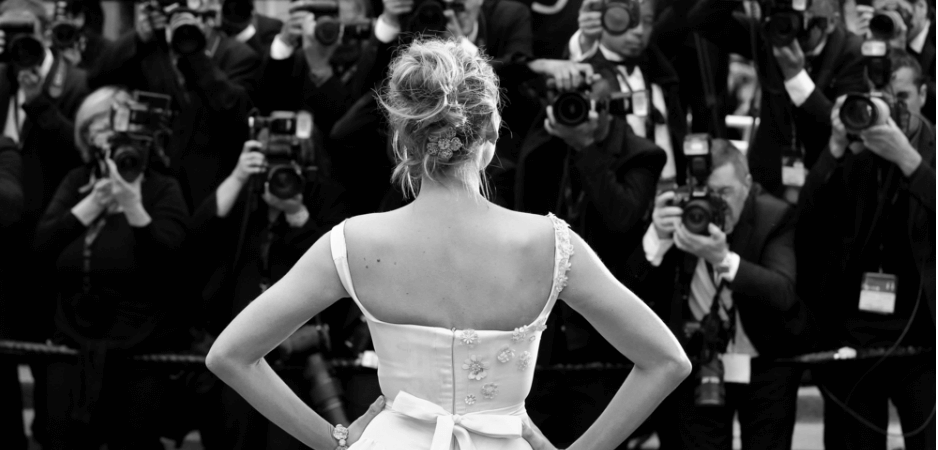

Interest in celebrities, as part of a broader preoccupation with the culture of entertainment, has infiltrated almost every aspect of life in modern society. Although interest in celebrities can be traced back to antiquity, contemporary manifestations of this fascination have risen in tandem with the development of consumer culture and the growth of the entertainment industry.

But what explains this fascination with celebrities? Is the appeal that celebrities have for many people a good thing? A fair amount of research points to issues surrounding the self and social needs as reasons for a fascination with celebrities. In some instances, people may be attracted to celebrities to help remedy chronic feelings of inadequacy or emotional distress. Such people can be described as suffering from what Phillip Cushman, called the “empty” self. Other people, however, may gravitate toward celebrities as part of a more normal human need to seek out, form and maintain social connections. The behavior of these people is governed by what we can call the “social” self.

Lynn McCutcheon and his colleagues have developed a theory of celebrity worship that describes behaviors motivated by both the empty self and the social self. Their theory describes three successively deeper and more pathological levels of celebrity worship. Therefore, the degree of celebrity worship that a person might have can be viewed as being on a continuum, with lower levels being relatively normal and governed by the social self, and deeper levels being more abnormal and motivated by the empty self.

According to McCutcheon and his colleagues, the mildest level of celebrity worship is the “entertainment-social” level, which can enhance social or entertainment activities. People enjoy discussing celebrities with their friends as part of everyday social interactions. The second, and deeper, level is “intense-personal,” in which interest in celebrities is more obsessive. At this level people show greater preoccupation with celebrities than they normally should. Finally, the deepest level, “borderline-pathological,” reflects more severe and pathological obsession and can even lead to stalking and erotomania, the false belief that one has an actual relationship with a particular celebrity.

At this deepest level of celebrity worship, people are too enthralled with celebrities, possibly to the exclusion of real life friends and activities. McCutcheon and his colleagues propose that interest in celebrities can be addictive and lead to increasing levels of preoccupation with celebrities in order to satisfy the addiction. Indeed, research on the theory has strongly supported the prediction that deeper levels of celebrity worship are related to negative outcomes, such as depression, anxiety and neuroticism, as well as poorer self-esteem and lower life satisfaction. McCutcheon et al.’s theory clearly illustrates that for some people celebrity worship is motivated by normal social needs of the social self, but for others it is driven by the desire to compensate for some inadequacy in the empty self.

The Empty Self

Cushman has proposed that the empty self emerged in the latter half of the 20th century in the West due to a combination of demographic, economic, sociocultural and psychological factors. The marriage of the disciplines of advertising and psychology in the 1920s led to the widespread adoption of the lifestyle solution, which prescribes the use of consumer products to help solve life’s problems by offering remedies for undesirable conditions such as poor relationships and a variety of health and hygiene needs.

Over time, the development of an independent secular personality was emphasized at the expense of religious character and a clear set of internal values. For some people, this has resulted in a version of the self that is too individualistic, independent of others, narcissistic and isolated, leading to a loss of shared communal values and meaning, values confusion, depression, lower self-esteem and relationship problems. The empty-self experiences a chronic, vague emotional need that the person unsuccessfully attempts to fill through such activities as ceaseless consumption of material goods, drug and food addictions, serial romantic relationships and even unjustified fascination with political figures and celebrities.

Although Cushman did not conduct empirical research to support his “empty self” hypothesis, other research offers strong evidence that he was correct. Celebrity worship and compulsive buying tendencies have been consistently associated with poorer psychological well-being, including poor self-concept clarity and proneness to boredom. Intense personal celebrity worship has also been found to predict the incidence of elective cosmetic surgery. Some research has observed evidence for a cultural shift over time, with more books, television shows and song lyrics featuring narcissistic behavior and generational increases in narcissism.

More support for Cushman’s theory can be found in recent comprehensive reviews of research on materialism, which have shown strong relationships between materialism and negative outcomes, such as lower personal well-being, lower life satisfaction, relationship problems and even poorer physical health. There is also evidence that materialism is increasing over time among young people. Grant Donnelly and his colleagues, in particular, reviewed evidence that materialism was related to the desire to escape from negative emotional states, similar to Cushman’s description of the empty self. Also consistent with Cushman’s view, L.J. Shrum and his colleagues have argued that materialism is motivated by a desire to construct and maintain identity, for example, to increase self-esteem, or to foster belongingness and acceptance by others.

The Social Self

We are social beings who need close supportive contact with others for both psychological and physical health. We have a need to belong, requiring ongoing positive relationships with others who care about us, and we gravitate toward others and enjoy positive social interaction under normal circumstances. These social tendencies are believed to be genetic, or wired in, and necessary for survival according to evolutionary theory.

Interest in celebrities can be seen as a natural result of this need for social connection. Celebrities are often portrayed as attractive and wealthy, with glamorous, exciting lives, in contrast to the more mundane, dull existence of fans. Information about the lives and work of celebrities permeates everyday existence, and the celebrity news cycle runs 24 hours a day. This coverage provides a compelling narrative that increases interest in celebrities, according to Neal Gabler (also see his book Life the Movie: How Entertainment Conquered Reality). Studies show that the most common leisure activity among Americans, the English and citizens of other European countries is choosing to become absorbed in imaginary experiences and social worlds provided by television, movies, books and video games, which typically feature celebrities.

Related research by Shira Gabriel and her colleagues has shown that social needs can even be met with the use of social surrogates, which are only symbolic in nature. Social surrogates include social worlds, which are stories or narratives, both fictional and actual, that people experience, including movies, books and television shows; parasocial interaction, in which a relationship with a celebrity or fictional character is one-sided; and artifacts or products, such as pictures, favorite foods from one’s past and Facebook status updates that remind people of others.

More recent critics continue to commonly blame celebrity and entertainment culture for moral decay, loss of values and the erosion of cognitive abilities. We are also too easily distracted from important events that really matter.

People who have lower self-esteem have been shown to boost their self-concept by thinking of a favorite celebrity. Similarly, people who feel rejected have had their sense of social connection restored by involvement in a favorite television show. Involvement in fictional narratives can also add meaning to fans’ lives and facilitate empathy and social skills.

Gayle Stever believes that parasocial relationships with both actual and fictional mediated personalities are to be expected from an evolutionary perspective, and that in most cases these non-reciprocated relationships are adaptive in helping people meet social needs for safety and security. Extensive interviews with fans of various celebrities over several decades has led her to conclude that parasocial relationships with either actual or fictional celebrities can be successfully integrated into normally functioning social lives of fans, although such relationships for an estimated 15 – 20% of fans result in intense-personal celebrity worship, which may be more problematic. For this minority of fans, the empty self is more likely motivating the attraction to celebrities.

There are additional reasons for the easy connections that fans have with celebrities. We experience the same emotional responses to fictional events as we do to real events, and although the former may be a bit weaker, they are, nonetheless, real emotions. Research on evolutionary theory suggests that people’s brains may not have evolved sufficiently to have different emotional reactions to fictional characters as opposed to actual acquaintances. Satoshi Kanazawa’s Savanna Principle, for example, suggests that the brain cannot understand and process events and situations that differ from the way they were in the ancestral environment. Therefore, media representations of celebrities cannot be easily distinguished from actual encounters with people. Consistent with this reasoning, Kanazawa speculates that people lower in intelligence may have a more difficult time distinguishing between their real friends and characters that they see on television.

Social Media

Emerging research on social media, however, shows that fans and celebrities can have actual relationships that go beyond parasocial ones. Fans who use Twitter to communicate with their favorite celebrity feel a more intimate connection. Celebrities who tweet often reveal more candid personal information and can create feelings of closeness for fans, in addition to managing their image, although in some cases the celebrity may not actually be the one managing the Twitter account. Lady Gaga has used a variety of social media to cultivate a large devoted fan base known as Little Monsters. Her web site gives access to her concert tickets and music, and provides a forum for fans to communicate with her (on occasion) and each other and to explore personal issues in a supportive online environment.

I love you little monsters 4eva. The last decades been a blast I will never forget. I can’t wait for the next. If you don’t have any shadows you’re not standing in the light. 💫I wrote “just dance, gonna be ok” right after one of the hardest times in my life. It was true. pic.twitter.com/mpx8XLPhfK

— Lady Gaga (@ladygaga) April 9, 2018

The increased use of social media to communicate with celebrities and the rise of reality television have led Joshua Gamson to propose that the most important trend in celebrity culture in recent years is that celebrities have become more ordinary and accessible, while many ordinary, unexceptional people have become famous.

Celebrities can reveal intimate, mundane and behind-the-scenes aspects of their lives on social media. Social media can even help fans to achieve their own measure of fame, which has been shown to be the main aspiration of many young people in recent years. Fans who have a greater interest in fame have also been observed to be more active on social media. Reality shows also typically highlight ordinary people and provide a quick path to fame.

Strong cultural forces also promote interest in celebrities. The media and entertainment industry has a market valued in excess of $700 billion in the United States, and it is predicted to exceed $800 billion by 2021. Worldwide, the market was valued at $1.72 trillion in 2015 and projected to reach $2.14 trillion in 2020. It should not be surprising, therefore, that entertainment themes dominate much of what we think about and do in daily life. We seem to have an insatiable appetite for all forms of entertainment and the industry is happy to oblige us.

Critics of celebrity and entertainment culture seem to become more on target with each passing year. As Daniel Boorstin predicted, we have become too preoccupied with what he called “pseudo-events,” interesting but meaningless dramas concocted by public relations agents, which distort reality and emphasize imagery and emotional reaction in lieu of logical and rational reflection. Video technology is advancing to the point where fake videos are increasingly indistinguishable from videos of real people and events.

Neil Postman observed how Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World more accurately forecast modern cultural changes than George Orwell’s 1984. According to Postman, while Orwell’s dystopia was oppressive and overtly controlling, Huxley’s alternative portrayed a more subtle and seductive subjugation. Huxley described a society obsessed with trivia and lulled into complacency with incessant pleasure and entertainment.

More recent critics continue to commonly blame celebrity and entertainment culture for moral decay, loss of values and the erosion of cognitive abilities. We are also too easily distracted from important events that really matter. Postman warned that, “There are two ways by which the spirit of a culture may be shriveled. In the first — the Orwellian — culture becomes a prison. In the second — the Huxleyan — culture becomes a burlesque.” There is probably no way at present to completely disengage from the effects of celebrity and entertainment culture. In order to try to keep a better perspective about these effects, however, we might adapt an old saying: Although we might keep our celebrity friends close, we should keep our real friends closer.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Photo Credit: Andrea Raffin / Shutterstock.com

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.