The news on May 14 that two Rohingya refugees have tested positive for the coronavirus in the densely-populated camps in Cox’s Bazaar, Bangladesh, is chilling for those who have been drawing attention to the vulnerability of refugees and other displaced people to the COVID-19 pandemic. It follows similar news from South Sudan and Greece: On May 11, the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR), reported that two people had tested positive in Juba, where two camps host around 29,600 displaced people, while the Greek Migration Ministry has confirmed two cases on Lesbos. Dr. Shamim Jahan, Save the Children’s health director in Bangladesh, warned: “Now that the virus has entered the world’s largest refugee settlement in Cox’s Bazar we are looking at the very real prospect that thousands of people may die from Covid-19.”

Medical experts, refugee agencies and activists have been sounding the warning that this was inevitable, and that the consequences could be catastrophic. And they have called for urgent action to protect displaced people wherever they are and whatever their status. For example, Lancet Migration, a global collaboration between The Lancet medical journal and researchers, implementers and others working in the field of migration and health, issued a global statement on COVID-19 and people on the move, arguing that all “should be explicitly included in the responses to the coronavirus 2019 pandemic.”

COVID-19 Will Have Long-Lasting Effects on Migration

They call for migrants and refugees to be transferred from overcrowded reception, transit and detention facilities to safer living conditions; the suspension of deportations; relocation and reunification for unaccompanied minors; clear and transparent communication including for migrant populations; and strategies to counter racism, xenophobia and discrimination.

Increasing Dehumanization

These measures are urgently required, but the extent of political hostility to unauthorized migrants — and, in many countries, the public hostility — mean that even such basic steps remain a remote possibility. The fact is that, despite their modesty, they represent a fundamental transformation of the politics of displacement. Natalia Cintra, Jean Grugel and Pia Riggirozzi point out that the concerns around the impact of COVID-19 on displaced people in terms of their health reveal how difficult their situation already is: “COVID-19 is not disrupting their otherwise ‘normal’ lives, so much as increasing their dehumanization still further.”

The fact is the world is locked into an international system of confinement of refugees, asylum seekers and other migrants that reinforces this dehumanization, a system in which they are identified as a problem that must be contained, even repulsed. For many of them, that system is not only oppressive but also highly dangerous and often fatal, as the Missing Migrants Project, which keeps a grim record of migrant fatalities throughout the world, lays bare.

COVID-19 is an additional threat to the lives of refugees, but in a system which refuses to recognize their full humanity, they will continue to be exposed to that threat in ways those of us confined within our own homes, with access to food, water, soap and health care, if we need it, cannot imagine. The pandemic adds a new level of precarity to their already extremely precarious lives.

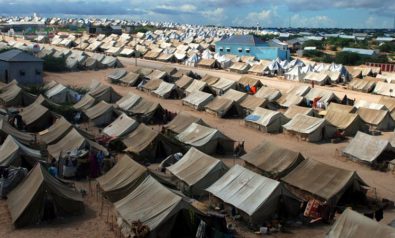

Anyone paying attention to what was happening in the camps and elsewhere knew this was coming. Louisa Brooke-Holland, a defense policy analyst at the UK House of Commons Library, warned in an April 9 briefing paper that refugee camps are especially vulnerable to serious outbreaks of COVID-19 because “they are high density settlements with poor access to water and sanitation and limited health services, and because the camps rely on host communities who themselves have limited means.” Her report focusses on the Rohingya in Cox’s Bazaar, where 850,000 refugees live in “highly congested conditions” in 34 camps, in a host community of 440,000 people and large numbers of aid workers.

Hygiene and sanitation facilities are inadequate and social distancing is not an option. According to Brooke-Holland, Cox’s Bazaar “lacks facilities to provide intensive care treatment, oxygen supplies and adequate Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) for health workers,” with the British Medical Journal warning in March that the nearest testing facilities are 400 kilometers away in Dhaka.

Effectively Detained

According to Human Rights Watch (HRW), around 128,000 Rohingya are “effectively detained” in government camps in Myanmar itself: “Most are trapped in dangerously overcrowded camps with severely substandard healthcare and inadequate access to clean water, sanitation, and other essential services. Many displaced people have underlying medical conditions and chronic diseases, putting them at high risk of suffering serious effects from the virus.”

In Rakhine state, around 130,000 Muslims, mostly ethnic Rohingya, have been confined in open-air detention camps since 2012, and there are 107,000 internally displaced persons in camps in Kachin and northern Shan states, displaced by fighting between the Myanmar military and ethnic armed groups. They lack access to health care, shelter, clean water, sanitation and food because of government restrictions on humanitarian aid.

There are similar challenges for displaced people around the world. The main concerns are for those living in encampments or being held in detention centers of some sort. Writing in The Lancet in March, Hans Henri P. Kluge, Zsuzsanna Jakab, Josef Bartovic, Veronica D’Anna and Santino Severoni comment that camps can present a severe health risk, with inadequate and overcrowded accommodation and lack of basic amenities like clean running water and soap, and poor access to health care, including adequate information. Basic public health measures, such as social distancing and self-isolation, are not possible or extremely difficult, and so “the concern about an outbreak of COVID-19 in the camps cannot be overstated.”

And it is not just the camps that are a concern. Migrants and refugees are also vulnerable in wider communities, “over-represented among the homeless population in most member states — a growing trend in EU-15 and border and transit countries,” according to the authors.

Victims of Deterrence

The European Union’s policies of deterring unauthorized migration are threatening to undermine responses to COVID-19. Sally Hargreaves and her co-authors wrote in the British Medical Journal in March that these policies have led to “displaced migrants living in camps, reception centres, and private and public detention facilities within and around Europe’s borders — all victims of European policies of deterrence to stop uncontrolled migration.” They are living in “appalling conditions” and lack access to food, water and health care. The overcrowding and poor hygiene in the many migrant camps around the Mediterranean increase vulnerability not only to COVID-19, but to other infectious diseases such as varicella, measles and hepatitis A.

Reporting on the experiences of refugees in Uganda, the country which hosts 1.35 million UN-registered refugees, the largest population in the world, Lucy Hovil and Vittorio Capici describe the situation as highly worrying: “They live in overcrowded conditions and there is insufficient access to hygiene supplies. This makes basic measures to stem to spreads of the coronavirus such as social distancing and hand-washing, difficult.” Many of them rely on aid, but the World Food Programme revealed a 30% reduction to the relief it distributes to refugees and asylum seekers in Uganda in April. Also, many international staff have left the field to self-isolate in their home nations, and the emergency measures put in place by UNHCR have had little impact. Not all refugees in Uganda are in camps, having decided to move to towns and cities where they have more opportunities to earn a livelihood, choosing this option over official assistance. But these urban refugees also face challenges given their uncertain legal status and increasing food prices.

Refugees attempting to flee instability in the Democratic Republic of Congo or South Sudan and claim sanctuary in Uganda are also facing difficulties as Uganda has closed its borders and suspended asylum claims. Jan Egeland, secretary general of the Norwegian Refugee Council, notes that border closures in Africa have left people fleeing danger unable to reach sanctuary. Kenya, Ethiopia and Uganda have almost entirely closed formal crossings, effectively shutting down refugee transit centers. According to Egelund, “Refugees are being left in limbo.”

The 5.6 million Syrian refugees and the 6.6 million people internally displaced in Syria face similar challenges. The Atlantic Council’s Pinar Dost reports that most at risk are the more than 900,000 people who fled Idlib and Aleppo to the Turkish border in December 2019, following a Syrian government offensive. “In living conditions where often the most basic needs are unmet, it will be extremely difficult to prevent the disease from spreading among displaced Syrians unless serious measures are taken,” writes Post.

Other Dimensions

There is also a gender dimension to COVID-19’s impact. Natalia Cintra and her co-writers draw attention to the situation of displaced women and girls in Latin America. The danger here is that the pandemic “may well deprive displaced women and girls of the essential protection services they depend on and exacerbate the risks they already face to their wellbeing and lives.”

Refugees and asylum seekers face challenges in Global North states as well as in the Global South. Destitution affects many asylum seekers in the United Kingdom because of limited access to public funds and exclusion from the right to work. Lubnaa Joomun comments for Refugee Research Online that because of these limits, many end up living in substandard accommodation, and “those forced to live in such appalling conditions, which fail to meet even basic human needs, become susceptible to infection.”

Those confined in the UK’s immigration detention centers are at great risk as well, “unable to follow the government’s instructions to socially distance,” according to Rudy Schulkind, writing in Open Democracy. “Hygiene is poor and cleaning products are scarce.”

Elsewhere in Europe, the default position on refugees and asylum seekers is to keep them locked up so that, as measures are eased, they are left behind. Human Rights Watch reports that while the Greek government began easing lockdown measures in May, allowing people to leave their homes without authorization, asylum seekers and migrants remain confined, sometimes in overcrowded reception centers. There has also been a failure by the Greek authorities to take basic steps to protect people held in the centers by addressing overcrowding, lack of health care, lack of access to adequate water, sanitation and hygiene products like soap. According to HRW, as of May 6, the camps on the Greek islands were six times over their capacity.

The Greek government announced on May 10 that such centers would remain under lockdown at least until May 21. The two positive cases of COVID-19 detected on Lesbos on May 12 have led some to call for the camps to be evacuated as a matter of urgency. Dimitra Kalogeropoulou, International Rescue Committee country director for Greece, told The Guardian: “Refugees living in camps have limited ways of protecting themselves from the coronavirus; if it does reach the camps, the severe overcrowding and absence of proper sanitation mean that it will spread rapidly. It is essential that the camps are decongested … [and] those most at risk are evacuated.”

The lives of displaced people are already filled with precarity, and yet in the face of this, states continue to make their world more dangerous by placing new obstacles in their way as they attempt to flee persecution, conflict, disaster and extreme poverty. If we are to join them in their struggle against this new threat from COVID-19, we must join them in their struggle against an entire global system that imposes danger across all dimensions of their lives. However remote the possibility of the transformation of that system might seem, the pandemic reinforces its urgency.

This urgency is shown by the fact that when the first version of this article was written on May 13, no cases of COVID-19 had been reported from refugee camps or other settlements for displaced people, but that has changed dramatically in a few days, and events will develop rapidly and, it seems, for the worse.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.