“Without our voices, we have no choices. And without choices, we could be stuck forever in violence.” A reflection on discussions with Syrians in and outside of Syria. This is the first of a two part series.

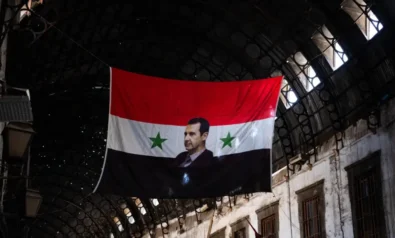

The civil conflict in Syria has raged for over two years. The large majority of aid workers outside of the United Nations World Food Program are no longer allowed within the country’s borders; they wait in Beirut, Lebanon and do what is possible from there. Now, potential intervention from external military forces appears to be gaining some traction. There are new reports of car bombs and slaughter on a daily basis, and without the media being allowed into the country it is hard to independently verify whether Bashar al-Assad’s government or the rebel groups are causing each incident.

The Human Connection Behind Closed Borders

By a twist in fate, I have come closer to the Syrian conflict than I would have ever expected.

In the last few weeks, my morning routine has been slightly altered. I wake up, get to my office, and before I even have coffee, I check if Amal is on Skype. Then I type a cheerful message and inquire about her family’s well-being, as they are sitting in the middle of Damascus. About three months ago, one of her cousins was kidnapped for several days. Sometimes there are power outages, but usually Amal has warned me ahead of time, so I don’t worry too much. I made her acquaintance through an NGO for which I volunteer time. While the world seems to be crashing around her, Amal continues to reach out to the rest of the world doing humanitarian work to the extent possible.

Amal is not her real name. Together we chose the pseudonym of Amal, which in Arabic means “hope and aspiration.” And that is exactly what characterizes Amal for me – her hope and beautiful aspirations for a united and peaceful Syria, as the walls continue to cave in around her.

Finding a Voice When No One is Listening

Amal recently explained to me that “without our voices, we have no choices. And without choices, we could be stuck forever in violence.” She has asked me to do something, anything. Amal holds a PhD in English Literature from a Canadian university. Throughout our conversations, it is evident that she is knowledgeable about North America and was deeply affected by the backlash from 9/11 and has worked to build trust between non-Muslim and Muslim communities, even informally, ever since. We never talk a lot about her time abroad, but Amal mentions that she loves Canada as much as she loves Syria because it was her time and experiences in Canada that opened her eyes and heart to the inter-faith dialogue in which she is now a fervent believer. Even though it is difficult, Amal feels that at the moment she does belong home in Syria. She aspires to write a book of poems and thoughts on all that is going on in the country. I am honored that she trusts me to share her thoughts about the world outside Syria, for now, under an alias in order to protect herself and her family from those within Syria who may not agree with her views.

The Human Backdrop

According to the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, more than 82,000 people have been killed, 1.2 million Syrians are displaced within their own nation, and 1.4 million Syrian refugees have fled to neighboring countries. With the number of countries where Syrians are welcomed being a small handful, while international scholarship funds dry up, the options are becoming more limited for those considering flight.

In wartime, the most important objective for those “stuck in the middle,” the innocent bystanders, is to immediately end the bloodshed and fear. In the case of Syria, the process and means by which this is done will profoundly affect generations to come, their relationship with their own nation and the international community. Depending on who “wins” the civil conflict, minority groups may suffer as never before. And depending on which countries in the west support the “winning” side, Syrians may or may not be welcomed in places around the world in the future. Unfortunately, what may be best for those inside the country may not coincide with what the international arena is able or willing to provide.

The View of a Syrian Outside, Looking in

Alaa al-Bagdadi, as if by fate, was introduced to me not long after I started to speak with Amal almost daily. Inspired and curiosity peaked by my interactions with Amal, I ask around to see if friends or acquaintances may know a Syrian, living outside of Syria, who is willing to speak to me freely about the situation. I receive an e-mail from a girl with whom I had choreographed a dance piece in college, describing her friend Alaa from the United Arab Emirates (UAE). He has close family members living in Syria and lots of thoughts to share. I liked Alaa instantly; he puts no time limit on our conversation and encourages me to ask anything and everything.

“At first, I understood my brother’s decision to stay in Damascus to finish his degree, but now I just hope that he will leave. So long as he stays in Syria, my mother will also never leave. And maybe it is time to go; things only seem to get worse,” he says. Alaa is a 28-year-old Syrian man who has lived in the UAE for the past eight years, working in telecommunications. He left Syria almost twelve years ago to study in Jordan; at that time, there was no English instruction for his topic within the Syrian university system. Ever since, he has never felt a strong desire to return permanently. He explains that since his family is Sunni, should he have stayed and done the mandatory military service (instead of paying a large fee to bypass service), he would have been treated poorly because of his religious views.

Assad’s government has often been lauded for protecting religious miniorities, such as Christians, within Syria. Yet, this likely arises from the fact that his own family is Alawite, which is a minority Shi'a sect of about 12% of the Syrian population. There are religious factors to consider for someone like Alaa who is Sunni. He goes on to say: “Without an Alawi business partner, I would not be able to have a successful business in Syria, for example. You see, my father made his main business outside of Syria, in Saudi Arabia.” But that does not mean that Alaa automatically trusts those groups opposing Assad’s government. His opinion is political rather than religious: “Assad’s family has been in power more than 40 years; it is a mafia. I think 90% of Syrians want them out. But the opposition army is not practicing true Islam through their radical actions; I don’t want to see any faction of them in power either.”

Searching for Beauty and Meaning in the Rubble

You can tell in your first encounter with Amal that she has a poetic soul. She explains the Arabic word “Barakah” to me as a holy blessing that was sent and filled the land. “I believe that if the mountains around Damascus and the lime trees, the Jasmine, and the rose were able to speak, they would tell you about the importance of this land. I am proud to be Syrian and a Muslim.” But she goes on to explain that Islam is being hurt by its own people. “I sympathize with all who have been hurt by Muslims, the world-round; and of course those who are hurt by non-Muslims as well.”

Amal reflects that Syria has not learned from the Turkish, nor French occupations of the past. “History is repeating itself. We never learned from our history and now we don’t learn from our neighbor, Iraq. The land was divided there, people are still killing each other, and further divisions are always arising.” Amal feels that Syria needs to learn how to solve its own problems and how to protect life and integrity. Then she sighs, and asks, “How?” Her message to the leadership in the United States, Russia, and all other potential arms-providers is to encourage dialogue and to participate in creating a history of peace, as weapons have brought nothing but destruction and further division. But then she realizes that there is no “free help;” those who have come into Syria in the past always had inherent interests in the land or religion. Furthermore, “to receive help that really makes a change, Syrians need to unite and want that help.”

I am deeply impressed by Amal’s assertiveness and certainty that peace can only arise from dialogue. This assertion touches me deeply, especially coming from a woman who just a day ago told me: “Dear, if I happen to be alive, we will speak; as we go out for food, normal things, and we don’t know if we will go back.”

From the Child’s Perspective

Amal keeps copious notes on the effect of the fighting on children in Damascus. She is prepared when I ask about the plight of children. A number of media outlets are reporting the situation in Syria is a disaster for children.

Amal gets more serious than in any of our previous conversations: “You see, dear…When the conflict and fights take place, whoever is in that area is exposed to danger. It is like a hell; whoever passes by will be affected by its flames.” She is very poetic; I just find myself getting heart pangs, wishing that I could hear more of her poetry, reflecting on beauty, not murder and explosions. She goes on to tell me that sadly these days, teachers are similar to those playing an active role in the war. “They all like to keep the hatred alive because that is how this sick game goes on. How is it possible to reach a child who only hears bad news all the time? These children are sensitized to the differences between types of explosions just by the kind of sound emanated. They know all the types of weapons, just like experts on video games in Western countries.”

*Read the final part of “Who Will Be Syria's Knight Sans Armor?” on May 25.

The views expressed in this article are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Image: Copyright © Shutterstock. All Rights Reserved

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment