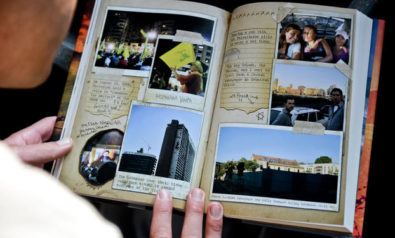

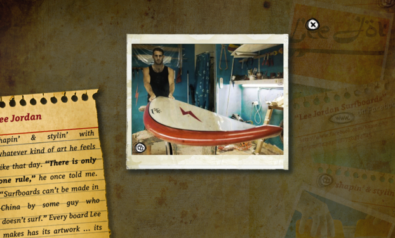

The following is the third of a six-part series of excerpts that Fair Observer will be featuring from Jesse Aizenstat's Surfing the Middle East: Deviant Journalism from the Lost Generation. Author's Note Leaving my Israeli friend Lee and the Haifa surfers, I reunite with an old journalist friend and we make our way to his flat in Bethlehem, the West Bank. Nobody can cross the Israeli-Lebanese border by simply meandering up the coast. So, I must test my theory about surfing from Israel to Lebanon, by going around the closed border, through Jerusalem, the West Bank, Jordan, fly over Syria, and into Lebanon. My surfboard Che is with me, and it feels ironic because there has never been a reason to take a surfboard to Jerusalem — a landlocked, biblical city on a hill. Jerusalem, Yerushalayim, al-Quds Traditionally, empires ruled the Middle East. They would rise like a wave from the depths, building to a crest so powerful its explosion would take everything that lay in its path. But like all waves, these empires eventually rolled back, leaving only a wet shore as proof of their past existence. And that is Jerusalem—a withered maze of ancient empires, built literally atop one another. If Haifa was the city of Arabs and Jews, then Jerusalem was the reef that caused it all to break. Yet Jerusalem would be a detour for me—the place I’d go because I couldn’t cross the closed Israeli-Lebanese border to Beirut, not more than twenty miles from the Haifa surf crew. And so the Holy City became a strange sort of portal for me: the place from which I would leave Jewish culture and take my first steps into the Arab world. No fine lines of transition, just crossing—with all the history and myth that make Jerusalem the prized shore of nearly every cresting empire . . . and the best medieval costume party on earth. And so, it was time to get grounded. Time to give Lee one last call and email my editor at the Surfer’s Journal to say I had just scored some waves in Israel and was now on my way to Lebanon with the story. It was time to round up Che and As-Salibi, and time check out of the Port Inn and head to the Haifa train station. It was time to do the job. When we arrived at the Haifa bus station there was the standard shakedown of Israeli security, but everything fell easily into place. I slid Che effortlessly into the bottom of the bus then climbed the stairs only to see row upon row of Religious Jews . . . in nearly every seat. I remember thinking something like, Holy Dreadlocked Moses! Surfing was never taught in this Hebrew school. What kind of sick joke was this, taking a surfboard to Jerusalem? Gliding through the ancient hills along the open Israeli roads, I started thinking that to the Jew, this city is Yerushalayim. To the Christian, this city is Jerusalem. To the Muslim, this city is al-Quds. But for As-Salibi and me, this city was lunch. We weren’t exactly on some theological crusade. The only mystical experience we were looking for was to sink our fangs into some kind of devilish street schnitzel. And when we got to Jerusalem, it was everywhere. Just a good stumble outside the bus station we found shops and stands filled with its greasy goodness. “Maybe we should take a cab,” I muttered, between gnawing at the schnitzel. “Nah,” As-Salibi countered, also gnawing. “Jaffa Street is pretty cool. With your surfboard, it will take just as long to find a taxi as walk.” So we decided to walk Jaffa Street, the historical no-man’s land that once nominally split the difference between East and West Jerusalem. This was the 1949 Armistice Line, all right. The Green Line. The same road that was once covered with heavy barbed wire, fortified with snipers and hunkered-down military units on all sides. Then, in 1967, when the Israelis captured East Jerusalem in the Six-Day War, Jaffa Street was cleared and brought under the blue and white of the Israeli flag. But even with the Israeli victory and the clearing of Jaffa Street, it was still a mission to negotiate a six-foot surfboard through the hurried people, blow-by buses, and jammed sidewalks. In all its history, there has never been a reason to bring a surfboard to Jaffa Street. There is no surf. Jerusalem is a landlocked Religious city on a hill. But our objective wasn’t the physical dance of wave riding. Jaffa Street was simply a hub that would connect me to Lebanon, as there could be no direct meandering up the coast from Haifa. The closed border was in the way, with both Israel and Hezbollah taking the fiercest aim at one another. The only way to surf up the Eastern Mediterranean coast would be this little experiment: come back down to Jerusalem, cross the West Bank into Jordan, fly over Syria, and land at the Beirut airport in Lebanon. It was going to require two American passports—as the Lebanese gleefully deny entry to any and all saps foolish enough to enter with a stamp on their passport from Israel . . . a country they’re still technically at war with. So there I was, walking on Jaffa Street, just passing on through to Lebanon, with perhaps the only reason anyone would ever bring a surfboard to this landlocked, Biblical city on a hill. I felt like some kind of Roman with a klutzy surfboard pilum, holding Che high by his shoulder strap as we stumbled through the streets together. Orthodox and Ultra-Orthodox Jews frantically tried to pass as I worked to negotiate Che around old street posts; new street posts; and even a pay phone, hidden under a collage of Hebrew letters. It was madness in all directions. Everywhere I looked there were people. A sudden blast from a passing bus blew Che wildly, like a half-opened parachute. Once, I nearly harpooned an old babushka with Slavic features. Was she Russian Jewish? This was rush hour on Jaffa Street. A new kind of ride with my board that even my wildest fantasies hadn’t quite captured. The further As-Salibi and I wandered, the more cosmopolitan Jaffa Street became, with outdoor coffee shops and cafés, stone neighborhoods, and overpriced trinket shops with polished old things I didn’t need. At some undefined point, the crowd made a philosophical—almost historical—shift from Orthodox to a Reform brand of liberal Judaism. And then, it shifted back. I suddenly remembered an Irish barfly I briefly met in Tel Aviv a few years before, who said, “Visit Jerusalem. I’m not even a religious person but it made the hair on my arms stick up. You’ll know when you’re there it’s a religious city.” And sweet Jesus, the mick fool was right! Jaffa is a far cry from the hedonistic streets of Tel Aviv, but just because everyone is more traditional doesn’t take the fun out of the place. The religious costume party is not only enjoyable to watch but has an amazing ability to make you feel hip, normal, and thankful to your parents for not rejecting the past thousand years of human evolution when they raised you. Then there are those who claim to feel that special spiritual something in the Holy City . . . but there’s not enough bourbon on my desk as I write here in Santa Barbara to get tangled with that. Though it strives to be, Jerusalem can never be an everyday city. Too many people examine this place from afar, like scientists peering off with wonder at some wonderfully lit planet too far from reach. When foreigners first visit Jerusalem, they tend to lay their own fantasies on the place, as many of them have spent a lifetime singing and praying and philosophizing about it. But what does it matter? It’s holy for them, too. Even if only in a cultural sense. Which is a major reason Jerusalem has so many names. It’s important to more people than could possibly be known. In all kinds of ways. Somewhere around this point of pondering the meaning of it all, there tends to be a dip southward as the mind echoes the same sort of passiveness that can be found in the residents of Jaffa Street. Who the f**k cares what everyone else thinks? When you’ve spent enough time in a holy place, the so-called holiness of it kills off whatever mystique actually inhabits it. But I had just gotten to Jaffa Street . . . so my dispassion was from that bulky fiberglass b*****d, Che, making my shoulders numb as I kept passing him off from one side to the other. And I could tell that it was the tourists—not the costume-party locals—who were looking at me in amazement. Perhaps a Californian with his surfboard wasn’t the idol they expected to see in the city that grounded their faith. Che and I smiled in amusement. As we continued down Jaffa, As-Salibi was out in front and I paused for another much needed moment of calm. It was imperative that I regroup. Sometimes when traveling, things get so massively overwhelming that it is in the interest of your own safety that you take a break before the scene gets too frightening. While you expect a certain payoff of personal growth from lunging yourself into unforeseen situations, there is always the risk of getting bucked off the wagon. And that can be a very bad thing. Especially in a place that is beyond your control, with people rushing by, while you are lugging a bag, handling a goddamn surfboard, and trying to inhale as much culture as can be safely whiffed. Holding this pause, I looked down to see that the hairs on my arms were on end—just as the mick fool had predicted! Continuing to tune out, I let my mind wander off to somehalf-nakedCatholic/pagan kid halfway around the world in Peru, on a high plane in the Andes Mountains, dreaming off into the distance about the historic spot where Jesus was crucified. Not too far from where I’m standing. A mean sense of awe started to sneak up on me . . . the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. And every step I took down Jaffa Street would lead me closer to the crucifixion site in the Old City. I shuddered with a blast of Jerusalem Syndrome, took a deep breath, forced myself to stop thinking about it, and moved on. Then I came around a small shelter. It was a bus waiting zone with Hebrew letters smothered all over it like the pay phone a few blocks back. I couldn’t understand the words, and the bulky steel of the foundation forced me to swing Che wide behind it, near the guardrail, and onto the steps of a shoemaker’s storefront. There, I saw a lone Hassid. Suddenly, in the familiar drawl of California English, he spoke. “Hey! Whatcha got in the bag?” I looked him over. The man was nearly identical to every other Hassid I had seen: black straight-brimmed hat, white collared shirt with the top button rigidly fastened, black belt, black trousers, black shoes—and a very nice black beard, which really tied it all together. “Oh, hey. What’s up, dude?” I replied, in that same brand of California speech. “Umm . . . it’s a surfboard!” “A surfboard!? In Jerusalem? Why?” “I’m doing a story for a surfing magazine. I was just surfing near Haifa.” Utter amazement took over. “Wow! I had no idea.” Then bewilderment took hold and words escaped him. “Yeah . . .” I started back in. “It was actually quite—” “See,” the Hassid burst out, “I’m from Long Beach, California. I surfed in L.A. once, but I had no idea you could surf in Israel!” Every piece of self-restraint I had was now geared toward not picturing this Hassidic museum piece trying to surf off the coast of Los Angeles in the sea of fake t**s and beach culture. “Do people actually surf here?” he asked. “Well, if they do, I’ve got to get to Tel Aviv and try it . . .” Muttering something about a surfboard, the Hassid ran his fingers through his long, black beard, then swiveled and disappeared into the shoemaker’s shop. He was gone as suddenly as he had appeared. Jerusalem. It was most definitely a trip. Read the fourth excerpt from Surfing the Middle East: Deviant Journalism from the Lost Generation on August 8. The views expressed in this article are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment