The following is the second of a six-part series of excerpts that Fair Observer will be featuring from Jesse Aizenstat's Surfing the Middle East: Deviant Journalism from the Lost Generation.

Author's Note

I’m still in the northern Israeli city of Haifa, and catch my first waves in the Middle East and haul to shore a 1,000-year-old anchor from the Mediterranean with Israeli surfers. Afterwards, my main buddy Lee takes me back to the Haifa guesthouse. On the way something happens that throws the combustibility of the 2006 war right in my face. While this Haifa paradise feels like the beachfront I grew up with in California, there is always the explosive reminder that it’s not.

Knoll of the Rocket

All along the Eastern Mediterranean there are harrowing extremes. On this divided coast, beauty runs just as deep as the illness of conflict. It’s something almost as timeless as the sea; nobody really knows when it started or why, or if it even has the capacity to go away. All people know is that it exists, in this moment of time . . . and its reminders are ever present, with the ability to sneak up on you, awakening your brain and tuning your senses to a brutish reality not natural to the California surfer.

And so it was like a methadrine-crazed bat that Lee darted out of his small Japanese four-cylinder car and ran across the pothole-ridden road. “C’mon!” he yelled. He had offered to give me a ride back to the Port Inn after hanging at Raouf’s house, but suddenly he turned off the main road.

Darkness had just set in—and there was wild and random brush scattered across the mysterious terrain that was hard to make out. Dull silhouettes of rock formations were spread across the path, giving off an eerie, time-capsule ambience, as if we’d driven into a 100-year-old David Roberts watercolor of Ottoman Palestine.

“C’mon, Jess!” Lee called, nearly running now. “I want to show you something!”

So I started after him, away from the light and up the shadowy knoll. The air felt warmer here than at the beach—thick, rich, exactly how the Nazis of any college English department would want the word Mediterranean to work as an adjective. The grass was squishy, growing darker as I trampled over its long shadows. As I ran, my shorts left my legs open to hitting random weeds and bushes. Potentially hostile creatures could have been lurking in the dark, ready to spring or pounce or whatever the hell such unknown things do in that part of the world. Were there snakes on the hillside? Maybe an unexploded landmine from an early Arab-Israeli war? I didn’t have time to think. And the faster I moved, the more I felt vulnerable to realties I didn’t yet know existed.

By the time I caught up to the madman, I had worked myself into a state of twisted passion. What happened to going back to the Port Inn? What was this Goddamn F***ing Surprise!?

Lee had stopped, panting, at the top of the dark and grassy knoll. He turned back to wait until I came up beside him. “Look down!” he ordered.

I did. Briskly. Ready for the worst.

But to my surprise, I saw nothing.

“No!” he said sharply. “Look here!” He pointed, forcefully. And his voice was commanding, like it had been cast from an iron den of institutional authority—the army? I wasn’t used to hearing my newly palled surf mate speak in such a way. This was serious. But what did it mean?

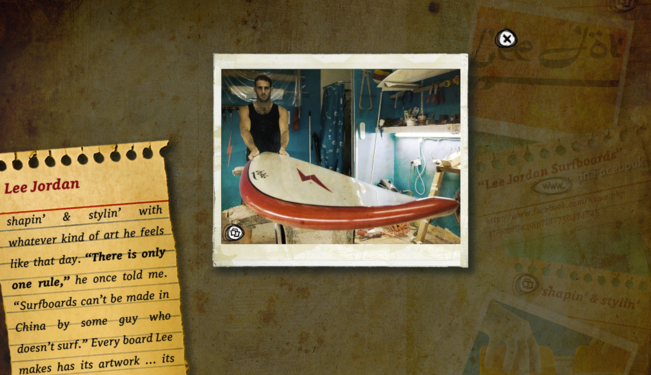

Lee pointed with both hands, callused from their daily duties of surfboard shaping. And then I saw it: a gnarled pipe was sticking up out of the ground a few feet. I hadn’t noticed it as I ascended the knoll. Okay, a stray pipe. Had we really run all the way out here for a pipe?

And zap—like a punch to the face—the reality hit like a boxer without gloves: these guys were messing with me, setting up some kind of Israeli joke on me! The American. I jerked my body around, scanning fervently for the surf jackals ready to pounce. But something seemed off. I couldn’t get it. And it was Lee, the way he looked at me through the shadowy dark—a glance of dire warning, as if my life could soon be wavering in the balance.

Had I gotten these Haifa surfers wrong? Had they just been playing along with me, waiting for the right moment to beat the hell out of this Californian?

There was no way to describe the panic I felt. I was alone and only a few weeks into the Middle East, and I hadn’t quite adapted to the subtleties of this climate. What if I had misread the character of these guys, who most of the time seemed so much like me?

Mad waves of bewilderment were now bombarding the tissues of my speedy cortex. What had I gotten myself into? The fear had sunk into me, standing on top of the knoll.

Looking at me in the twilight, Lee saw that his Goddamn F***ing Surprise had left my mind reeling with fear. He seemed confused by this but shrugged it off, and went back to the feeling that caused me to freak.

He spoke in a sober voice. “This metal pipe used to be attached to a sign. In 2006, a rocket from Lebanon hit this sign.” Lee’s gruff hands were playing out a shadow drama with the stubby pipe.

Lee pointed at the ground beneath my feet. “Right where you are standing was a hole.” Then his deep-set eyes twisted toward mine as he uttered the name that gave me The Fear: “Hezbollah.”

We both fell into silence.

His expression slowed the tempo of my heart. This was a matter of life and death. But it wasn’t about me. I had only misinterpreted Lee’s grim seriousness because I wasn’t from Haifa; I wasn’t used to surfing with the very real possibility that rockets could land on the very soil where I was standing. They could hit anywhere, at any moment. As they had in the 2006 war.

In California, there is no rocket threat and it would be ridiculous to even think of it. Clearly, Lee had caught on to this. He sensed that I was only enjoying myself like a houndish surf mutt, not tuned in to the guarded Middle East manner that defines a Haifa surfer. And that irked him—but not in any mean or malicious way, just enough to make him wheel his small Japanese four-cylinder off the main road and give me a goddamn heart attack by showing me the knoll of the rocket.

Very much unlike California surfers, Haifa surfers live under constant duress, a wrenched tightening in their gut that reminds them that this Eden of summer surfing is an illusion—there is no peace along the Eastern Mediterranean. Lee knew it would have been a crime to allow a California surfer to see only the lucid waves and not the red paint that makes Haifa a target for random rocket fire. Fifty miles north were an estimated 50,000 Hezbollah rockets in South Lebanon. They were pointed at every Israeli place I describe.

Since arriving in Haifa, I had been so locked into my “duder” vibe that pondering the toils of the Middle East seemed absurd. It wasn’t till that night on the knoll that the haggard truth hit: we were surfing in Rocket Country.

My mind checked back in the middle of Lee’s explanation about how the sky was particularly open to the Lebanese north here. And yes, this elevated knoll had taken one of the 4,000-plus rockets Hezbollah launched in the 2006 war.

“All these little holes in the tree . . .” Lee broke the silence, showing me the holes left from the exploding ordnance. And then he paused—switching to his own dimly lit nightmare from the summer of 2006. “When the war started I was at my parents’ house. We were eating dinner when the first rocket fell . . . it hit somewhere down the street. We all knew what it was because we’d been warned by Army Radio that Hezbollah had captured a few of our soldiers. It was war.

“Israel always goes to war for its soldiers,” he continued. “But we didn’t know how big . . . how many rockets. I went outside my house and looked far down the street along the Haifa waterfront and saw the smoke. Then I heard something. Another rocket, I thought. So I dove behind one of those green dumpsters and took shelter as it came crashing onto the street, hitting a parked car on my block just a few meters away from me. I was that close!

“You gotta remember, man, those Katyusha rockets are not guided for a reason . . . they are meant for us. The civilians.”

During the 2006 war, I was glued to the TV, reading all the live reports I could find. Hezbollah and Israel both let each other have it, hitting at their most valuable commodities: their civilian populations. Standing next to Lee, I felt an emotional blast that couldn’t be felt from California . . . in all its mind-blowing shock.

I had tasted the fright of war in Nablus, the West Bank, when I was there in 2007. But I thought I had grown hard to the Middle East—that it couldn’t affect me this second time around. But I was wrong. There was no way to surf the Middle East and not get lured back into all the grit of this place. It’s a ghost that would appear at the most critical moments, across all lines, no matter whom I had yet to meet on either side of the Israeli-Lebanese border. It was something that was stuck in me.

Read the third excerpt from Surfing the Middle East: Deviant Journalism from the Lost Generation on August 1.

The views expressed in this article are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment