In 2019, India produced over 1,800 movies, making it the world’s largest film industry in terms of numbers; this dwarfs the 792 produced in both the US and Canada combined. Bollywood, as Mumbai’s movie industry is known, distributes its films around the world and is particularly popular in South Asia, the Middle East, Africa, the US and Europe.

Why Fame Can Be a Nightmare

For India, Bollywood is the most important cultural soft power, gripping millions of viewers domestically and internationally. Soft power is the ability to shape the preferences of others through science, diplomacy, sports, religion and culture. This allows a country to attract other peoples through seduction rather than coercion. According to India Brand Equity Foundation, the Indian media and entertainment industry, which Bollywood plays a major role in, has “the potential to reach” $100 billion by 2030. In 2019, Bollywood made more than $2.8 billion. Before the COVID-19 pandemic led to major financial losses, the industry had been projected to hit $4.5 billion in 2021.

“The White Tiger”

Yet despite being worth so much, Bollywood has once again missed out on the chance to get the last shining prize for its soft power: an internationally acclaimed award. On April 25, India will be part of the 93rd Academy Awards, but not as a result of a Bollywood flick. “The White Tiger,” a Netflix production directed by Ramin Bahrani, is nominated for best adapted screenplay. Based on Aravind Adiga’s Booker Prize-winning novel, the movie was shot in India but not produced by any of the hundreds of Bollywood studios located in the country.

“The White Tiger” tells the story of Balram — played by Adarsh Gourav — who moves from a poor rural village to Delhi to become a rich man’s driver. After deciding to commit a crime to escape the complex stratification of Indian society, he becomes wealthy himself. The rags-to-riches story is as rare as a white tiger, as the metaphor of the title suggests. Paolo Carnera’s cinematography frequently shows the dirty streets and misery of life in India for the poor, while Bahrani’s script is full of jokes and criticism about the country’s poverty and social inequality — completely different from what we are used to seeing in most Bollywood movies.

Hollywood is recognized for its achievements in production design, cinematography, screenplay, acting and directing at major festivals in Cannes, Berlin and London. Yet Bollywood continues to miss out on awards, a crucial prize for any movie industry. The same thing happened in 2009 when “Slumdog Millionaire” — which tells the story of Jamal Malik (played by Dev Patel) growing up in Mumbai slums — won eight Oscars, including best picture, best director and best adapted screenplay. That movie was based on Indian writer Vikas Swarup’s novel, “Q & A,” but shot by British director Danny Boyle.

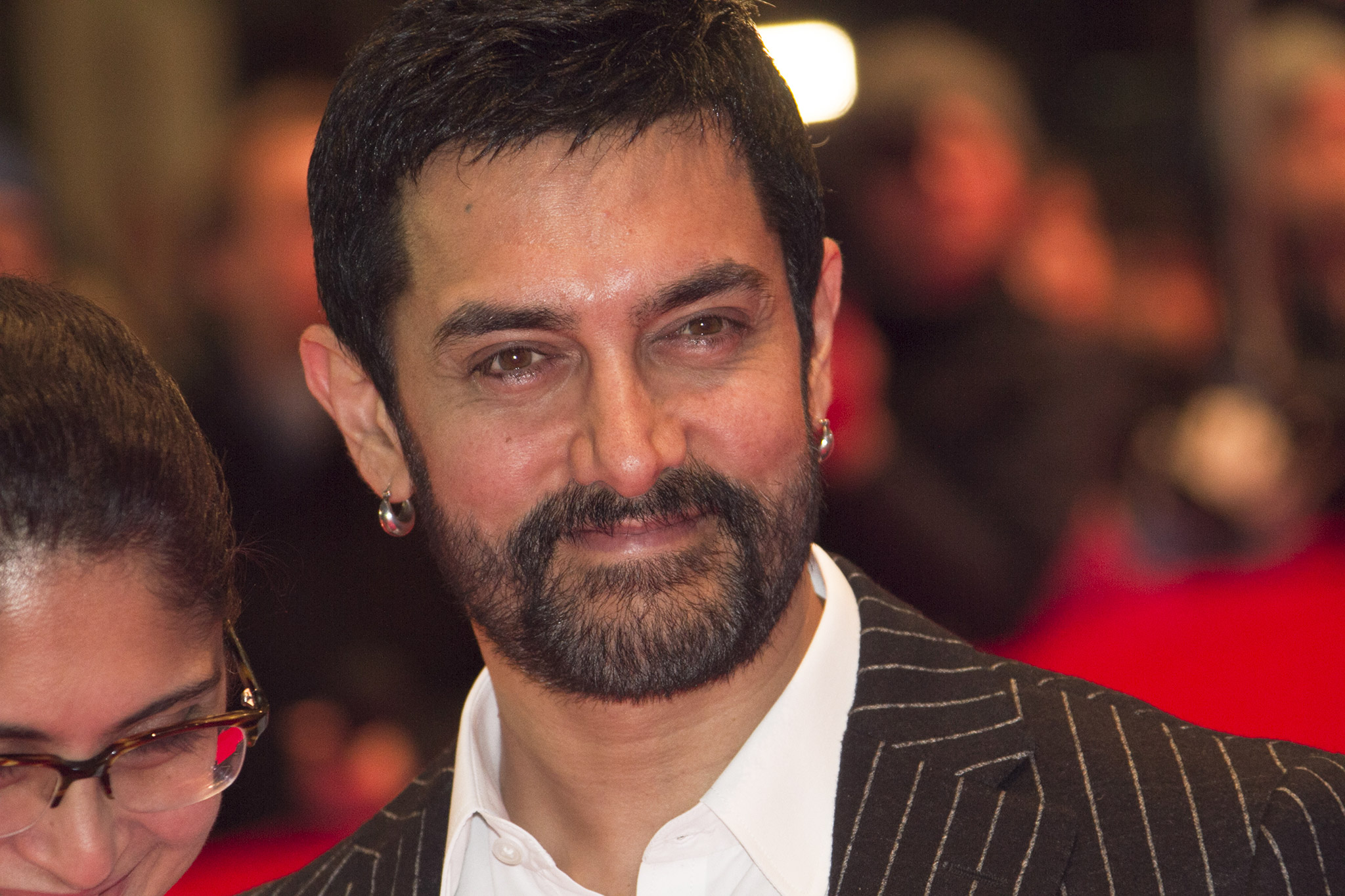

The closest Bollywood came to an Academy Award was with Mehboob Khan’s melodrama “Mother India,” which was nominated for best foreign language in 1958; the movie told the story about the struggles of a woman raising her sons alone. In 2001, Bollywood superstar Aamir Khan produced and acted in “Lagaan: Once Upon a Time in India,” which centered on a small village in Victorian India staking its future on a game of cricket against the British rulers. The film was nominated for best foreign language a year later but failed to win.

Bollywood’s Shortcomings

So, why can’t Bollywood conquer Hollywood and win a golden statue? I went to India in 2008 for an investigation into the country’s movie industry, which also led to my first book, “Diário de Bollywood” (Bollywood Diaries), released in 2009 in Brazil. Before packing my bags for the trip, I watched over 50 Bollywood movies to prepare my questions for the producers, actors, directors and executives of the industry. I soon realized that all those films back then had something in common: there were no sex scenes or nudity, they never mentioned or critically analyzed India’s social caste system, and they avoided making political comments.

Bollywood movies lack gripping human stories and resonant storytelling, which is why they are unable to transcend their culture. They provide an escapist fantasy to Indian audiences but do not work for most viewers outside India. These non-daring storylines lack the quality to win awards at major festivals, including the Oscars. So, why can’t a multibillion-dollar movie industry improve its films? The simple answer is that it can but won’t for two main reasons: escapism and censorship.

First, Bollywood has become a form of escapist entertainment from the reality of India. Often three hours long, the movies are usually full of rich and beautiful stars, singing and dancing and exploring their love lives, only to be interrupted by cruel villains who are defeated in the end. India’s post-production is among the top of the world in special effects, color and sound corrections, displaying beautiful scenes that serve as distractions to the hundreds of millions of Indians who live below the poverty line.

India is one of the oldest cultures of the world and is extremely rich and diverse. It’s also a modern country with cutting-edge technology. However, all those social, economic, sexual, cultural and even psychological changes and diversity are not embraced in most Bollywood blockbusters. Instead, they are distanced themselves from reality and offer trite stories as entertainment.

Second, the Cinematograph Act of 1952 determines “principles for guidance in certifying films.” Censor boards were set in production areas of India, such as Mumbai, Kolkata and Chennai. The closest to a sex scene that Indian movies largely feature quick kisses and partial nudity. If a film does not meet the guidelines set for “decency or morality,” then it doesn’t receive the certificate that allows it to be screened in movie theaters.

In the 2000s, with the arrival of the internet and the rise of downloading foreign movies, often pornographic, some changes were seen in Bollywood. In 2013, Sunny Leone, a Canadian-American former porn star of Indian descent, debuted in the film “Jism 2,” an erotic thriller that shows her topless from behind while being intimate with a man. Yet India, the country where Kama Sutra originated, still doesn’t make movies with deep kissing, explicit sex scenes or bold storylines.

That doesn’t mean that films with sex and nudity are better than blockbusters with music and dancing. Good movies often reflect creatively and boldly the changes in society and the world. Hollywood absorbed those changes in post-Vietnam movies such as “Born on the Fourth of July” (1989) and “Full Metal Jacket” (1987), in contrast to jingoistic and formulaic “The Green Berets” (1968) and Rambo: First Blood Part II (1985). All four films were box office hits, but the first two — directed by Oliver Stone and Stanley Kubrick, respectively — established Hollywood’s international reputation because of their sophisticated stories about the Vietnam War.

The Challenge Facing Bollywood

Bollywood is trying to emulate Hollywood. Whistling Woods International, a film school in Mumbai with American investors, is teaching aspiring film professionals. “In India, we must prepare our students to begin at the top of the movie pyramid, because the base pays almost nothing,” said Kurt Inderbitzin, the dean of the school back when I visited India. “Our challenge is to teach students to develop good characters and directing skills, since many of them arrive here with prejudices, imagining they don’t need to learn this kind of stuff, although these are the basic elements of a good film, like the concept of gravity for an astronaut.”

Better films lead to international awards and increase the chances of reaching commercial movie theaters. Better box office results in big markets like the US and Europe would help Bollywood develop India’s soft power. Bollywood faces major competition from streaming services like Netflix, Amazon Prime and Disney+ that are producing films and television series themselves. Bolder and richer movies may be just what Bollywood needs to keep conquering the hearts and minds of the public in the 21st century.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.