“I dreamed of my patient’s face, so hopeless, and as I tried to wake him, I saw his head flopping back and forth, his eyes rolling, his jaw clenching up and down.” Nikhil Bamarajpet, a 21-year-old volunteer emergency medical technician (EMT) and president-elect of Stony Brook University (SBU) Volunteer Ambulance Corps, woke up to this dream on April 18. That was the night after the New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH) issued the new cardiac arrest protocol that allegedly prevented Bamarajpet from saving the life of a 50-year-old father of two. “In the dream I started CPR, which was something that didn’t happen in real life,” he says.

Putting it in T.S. Eliot’s words, last April was “the cruelest month” for New York’s Suffolk County. By mid-month, its community of 1.5 million people had registered 25,000 positive cases and 1,500 hospitalizations. Intensive Care Units were overloaded with COVID-19 patients and were expecting many more to come. On April 17, the New York State Department of Health, Bureau of Emergency Medical Services and Trauma Systems issued a new protocol. Its emergency guidelines instructed paramedics like Bamarajpet not to initiate the customary 20-minute resuscitation when patients undergoing cardiac arrest were found without a shockable rhythm (i.e., with no pulse).

Will COVID-19 Be Another Pearl Harbor Moment for America?

The NYSDOH memo justified this as “necessary during the COVID-19 response to protect the health and safety of EMS providers by limiting their exposure, conserve resources, and ensure optimal use of equipment to save the greatest number of lives.” However, the same protocol was determined as “unnecessary” and officially rescinded after only six days.

Haunted by Nightmares

Indeed, Bamarajpet was the first unlucky EMT in the Central Islip department to apply the new standards announced as recently as the day before. Along with Bamarajpet, unlucky was also the man who happened to have a heart attack within that unfortunate week. His death, just like that temporary protocol, was also unnecessary. “After I woke up, I thought about what could have happened if I had just done the protocols as they were [before April 17th]. We could have saved him, but that’s not really something that I am supposed to be entertaining. These are my protocols, and even though I may be disagreeing with them, it is a large part of my job to uphold them,” Bamarajpet says.

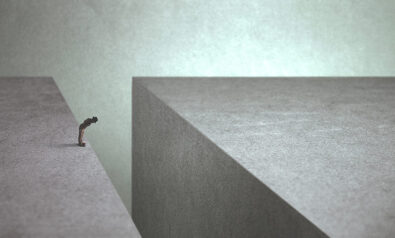

Like Bamarajpet, fellow volunteer EMT Elizabeth Vargas, a 26-year-old undergraduate at SBU, is haunted by nightmares. In her recurring dream she takes patients in her personal car, attempting to drive them to the hospital. “And the entire time there are all these barriers and I can’t get my patients through. I don’t have any supplies to help them and I can’t physically access any hospital. Do you know how it feels not having resources to help a patient?”

Daily, she recounts, they’re “facing a new barrier to care, to help people, with limited resources. And facing all these barriers, it feels like it doesn’t matter how hard we’re working. We’re failing our patients and I think that’s something that all of us will have to deal with when all this goes away. It’s the extreme guilt of — did we do enough? Were we helping them enough? Could we have done something differently? Could we have been more vocal? Could we have prevented some kind of death or suffering. It’s like living through a nightmare.”

These days, Vargas explains, nightmares are common among health-care workers. The traumas they face during these days of COVID-19 emergency are reflected in dreams, replicating their hand-to-hand combat with the virus. Sometimes it’s a repetition of what has gone wrong. Sometimes it’s a revision mending the powerlessness experienced while attempting to save their patients. This comes as no surprise. Many of them bear the post-traumatic wounds from both their daily exposure to the risk of infection and the reiterated moral injury of not being able to save lives they feel they should have saved.

It is hard to keep track of the exact number of volunteer EMTs among New York State’s 65,000 emergency medical service (EMS) providers who have been on the frontline during the COVID-19 crisis. Many of them, while being paid by some agencies, were also volunteering for others. What we do know is that they often worked 20-hour shifts with inadequate personal protective equipment (PPE). This regime of intensive, unprotected work is the most likely cause of the 83,365 infections and 463 deaths among US health-care personnel currently reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

In fact, Vargas reports that they’ve been wearing three-weeks-old N95 masks which, she explains, should instead be changed after each patient. During her ambulance rides, she “breathes” for her patients by “bagging them” through manual ventilators with no filters to protect her from potentially infected droplets. “Bagging people for entire transports during this COVID-19 crisis is the most dangerous thing you can do other than CPR. It’s very ‘aerosoling’. You’re taking that air and forcing it in and out, over and over again, with patients expressing air and possibly liquid or vomit from their mouths.”

Survivors

Understandably, after weeks of riding with the virus, young undergrads like Bamarajpet and Vargas have become full-fledged survivors. Yet they’ve been elevated to the status of heroes by the citizens, legislators and institutions rushing to scatter the SBU campus with “thank you” signs that praise the heroism of health-care workers fighting COVID-19.

Vargas rejects this rhetoric. “They’re trying to make me a martyr or a hero, and I’m neither,” she says. She paints a problematic relationship with the same institutions that are currently taking pride in the heroism of her fellow volunteers: “It’s really frustrating because the ambulance agency on campus has dealt so poorly with us members. [After SBU campus shut down for the virus outbreak on March 19th,] everyone who got to leave, got their housing money returned to them, but the EMTs who remained on campus to continue riding on the ambulance during the pandemic, didn’t get their money back. They’re paying to live here for the sole purpose of volunteering. So, for the university to put a sign outside our agency that says, ‘heroes work here’ is insane.”

Bamarajpet, in turn, appreciates the public display of gratitude such as the “thank you” signs and food donations. However, he is also disappointed by people’s lack of respect for preventive measures and by their increased hostility either when they are told they should or should not go to the hospital. Primarily, he’s afraid the community soon may no longer benefit from the important service provided by his fellow ambulance volunteers at SBU: “A lot of the survivability of our agency depends on younger personnel coming and learning. I have a fear that in the fall, if all classes turn online or hybrid, we still won’t get free or subsidized housing. If that happens, I fear that many of our members won’t be able to come back, that we won’t have district coverage, and that we’ll have a personnel shortage.”

At SBU, today’s heroes, the health-care workers, and yesterday’s heroes, the veterans, seem to share the same destiny. They are thanked and praised in words while allegedly being neglected and exposed to unnecessary risk. John Milone was 99 years old and survived the sinking of the USS Lexington aircraft carrier during the battle of the Coral Sea in World War II. He did not survive this pandemic, contracting SARS-CoV-2 at the Long Island State Veterans Home (LISVH), which to date has lost more than 80 veterans to the virus. Indeed, the story shared by Kathy Caruso, his daughter, seems like a tragic race against time.

Today’s Heroes

On March 24, the facility reported its first case. On March 31, one person tested positive in Caruso’s father’s unit. During a routine phone call on April 1, Caruso recalls, a caregiver told her that the infected patient was “walking around with no mask on.” Caruso claims she called Executive Director Fred Sganga to suggest using a vacant space within LISVH as an isolation unit. “I’m begging you to set it up to isolate! There’s only one in my father’s unit. Get him out of there, please, I’m begging you!” This was her plea, to which, she says, Sganga replied that at that point they just had to assume they were all exposed.

Sganga would not consent to her request. When I reached out to him for a comment on Caruso’s claims, he stated that they “were holding those areas for overflow from SBU Hospital,” claiming that “from day one the facility followed all the guidelines of the CDC, the NYSDOH, the CMS, and the VA.” In fact, for Alzheimer’s and dementia patients like Caruso’s father, those guidelines leave it up to the facilities to determine whether it is safer to maintain care of residents with COVID-19 on the memory unit with dedicated personnel.

“Do you think that these veterans, during World War II, would tell you they did the best they could by following basic guidelines? No, they went above and beyond. Now it’s your time to be a hero to them right now,” Caruso insisted to Sganga, in vain. Her father, John, who tested positive on April 11, was hospitalized on Easter Sunday and died on May 9, a day after the 75th anniversary of Victory in Europe.

It is not hard to understand why Caruso’s anxiety was anything but appeased when told that the nursing home was complying with the guidelines. On March 11, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo had issued an order that restricted visitation at adult care facilities (ACFs). Not being able to see their dear ones must have been painful to the residents’ families, but perhaps still tolerable in the name of protecting the elderly population of the ACFs who were particularly vulnerable to the new virus.

The directive that followed on March 25 was much more troubling. “No resident shall be denied re-admission or admission to the nursing home solely based on a confirmed or suspected diagnosis of COVID-19. Nursing homes are prohibited from requiring a hospitalized resident who is determined medically stable to be tested for COVID-19 prior to admission or readmission,” ordered the governor, turning New York’s nursing homes into something far removed from the safe haven they should have been. Forcibly, he may have opened them to infection due to the “urgent need to expand hospital capacity in New York State to be able to meet the demand for patients with COVID-19 requiring acute care.”

Legal Shield

Given the current death count of 5,300 presumed deaths among nursing home residents, questioning these administrative decisions is inevitable, but doing so in court may prove to be impossible. In the wake of the pandemic, on March 7, Cuomo issued an executive order that made health-care providers immune from legal liability in the case of injury and death resulting from COVID-19. Later that month, embedded in pages 346-7 of the New York State’s annual spending bill, that immunity was confirmed and extended.

The new legal shield now also protected the administrative staff of health-care facilities and nursing homes, such as any “health care facility administrator, executive, supervisor, board member, trustee or other person responsible for directing, supervising or managing a health care facility and its personnel or other individual in a comparable role.”

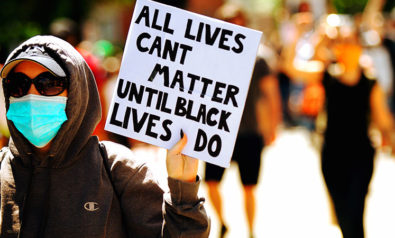

It’s a short step from immunity to cover-up. Kathy Caruso’s claims, along with those of countless health-care workers and patients whose mental and physical health may have been recklessly exposed to risk, may never turn from allegations into forensic evidence and historical truth. Under this preventive obstruction of court proceedings, the gratitude publicly displayed by institutions during this health crisis acquires the dubious aftertaste of gratitude without justice. As they gratefully praise their “heroes,” what type of heroism do they honor? Surely not the rebel kind invoked by Caruso when pleading with Sganga to do more than prescribed by the guidelines. Rather, they praise the stoic heroism of those who obey orders, persuaded of the need for sacrifice.

In the stories reported here, two fathers, and many other patients, have arguably been sacrificed on the altar of the common good. They have been sacrificed so as not to clog intensive care units and make room for those who had the most chance of making it, with more years to live. Each in their own way, Sganga, Bamarajpet, Vargas and innumerable other health-care workers have had to negotiate between the ethical obligation to provide care and the restrictions imposed by emergency protocols on the rescue of human lives.

Postponing the time of proclaimed heroism and honors, it might be wise to support those who are still battling COVID-19. In solidarity, when the time of health emergency gives way to the time of reflection, the burden of “extreme guilt,” to use Vargas’ words, should be shared. “Were we helping them enough? Could we have done something differently? Could we have been more vocal? Could we have prevented some kind of death or suffering?” We shall turn Vargas’ questions over to those who mandated protocols and guidelines, and, first and foremost, to those whose denial and late response to this pandemic made such emergency policies necessary.

*[The piece was updated on July 1, 2020 at 11:35 GMT.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.