Venezuela’s dictatorship has proved to be highly resilient. It mutated from a lively democracy in the second half of the 20th century to a hybrid regime where unfree and unfair elections were held and repression reigned, giving way to the current dictatorial domination. In the process, it also destroyed the economy and brought down most institutions. Moreover, it has become a co-opted state where a variety of criminal groups, including narcotics, operate freely.

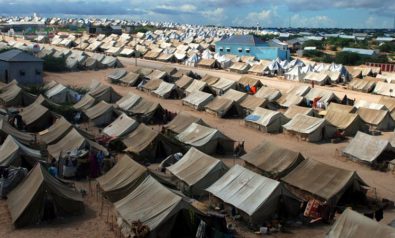

Yet it is perhaps the collapse of the economy, including the century-long prosperous oil industry, that has brought about a highly dystopian world where the crudest mechanisms of a war economy flourish, favoring control of the population at the grassroots level, a crude exchange of food and medicines for political favors. In 2016, the late Hugo Chavez’s planned breakdown of a weak market economy under the pretext of building a new brand of socialism led to a humanitarian crisis — with drastic shortages of food and medicines — and then to the largest migration crisis in the world, second only to Syria. This could bring total collapse and famine to Venezuela under the new conditions created by the coronavirus pandemic.

US Intervention Will Make Things Worse in Venezuela

Although most international analysts agree on many of these trends, there is no consensus either on which of these features dominates or on how to bring back democracy and avoid a potential humanitarian disaster. Some observers rightly point to the fact that the bulk of the narcotics going through Venezuela is not decisive to the US drug trade. They fail to consider, however, the extent to which — different to other countries — criminal groups form part of the Venezuelan state.

Other experts, members of international organizations or even countries rejecting the current regime may agree on the trends but not on the solutions. The best way out of the tragedy, many of them argue, is to seek a negotiation between the different poles of Venezuelan politics, especially where two powers seem to dispute legitimacy. One led by the president of the national assembly, Juan Guaido, claims symbolic legitimacy while the other, led by the de facto president, Nicolas Maduro, holds most levers of power (institutions, the military, the police, governorships and the like).

It seems to have been forgotten that all prior attempts at negotiations have always failed because Maduro and his ruling elite lack the right incentives to abandon power. As has transpired from those attempts, negotiators on the democratic side always noticed that their counterparts from the regime were not afraid of the consequences if no agreement is reached.

A National Crisis Becomes an International Hotspot

The last straw in the Venezuelan conundrum may perhaps be the most critical at the moment: The Venezuelan crisis is no longer a national or even a regional problem. In the last decade or so, it has truly become an international crisis, just like Syria a few years back, Cuba in the early 1960s or Suez in the 1950s.

Blasting the Trump administration for its intervention in Venezuela has become a recurrent theme for many analysts, either by arguing its importance in a reelection year, due to its importance in the Florida electorate or simply as a revamping of the Monroe doctrine. But most people fail to admit that Venezuela turned into a contested international spot since the beginning of Chavez’s rule. In the aftermath of the 2002 coup in Venezuela, Cuba became directly involved, not only with the use of its doctors in the creation of the wide and much-publicized primary care network, but also in military counterintelligence, presidential security and in other fringe business.

Despite its current reticence to continue its involvement, China was for at least a decade Venezuela’s main creditor, with oil loans that amounted to $50 billion since 2007, of which around half still remained outstanding by 2019, after continuous renegotiations. But Beijing offered a long list of additional loans, directly related to its involvement in different industries, like railroads, house construction, bridges and other infrastructure facilities. China avoided getting entangled in more direct political or security interventions, apart from building a satellite that allowed Venezuela greater telecommunications autonomy — hence, greater military security — until it collapsed a few weeks ago.

In contrast, typical of its highly assertive geopolitical stand, it is Russia that has higher stakes in Venezuela, mainly in two strategic areas: arms and oil. In the former, Russia sold around $10 billion in a wide range of armaments, including missiles, airplanes, helicopters, tanks, infantry fighting vehicles with anti-tank missiles, rocket launchers, automatic rifles and many others, as Chavez maneuvered to break off from US military influence.

At the peak of the deals, Russia’s armament companies deployed up to 2,000 technicians for support, declining drastically in the last couple of years. At the same time, mainly through oil giant Rosneft, Russia has invested around $9 billion in Venezuela’s oil — mostly in its heavy oil component — since 2006. Most of the investment in both areas took place through direct loans. While more eager than China to cash in their loans (close to 80% by the end of 2019), Russia has been far more supportive of Maduro, risking for some time the use of Rosneft’s wide trading network to grant oil sales throughout the world, even under US sanctions.

On the opposite side, in recent years, a vast effort has taken place in both Latin America and Europe to isolate the Maduro regime and push for free elections. This is either through minor sanctions, mostly directed at individuals in power in Venezuela, by breaking diplomatic ties or by abandoning recently created regional organizations like the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR) or the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC), which were promoted by Chavez in his golden years.

But without doubt, the US has been the most important international player in Venezuela’s turmoil. Early after taking office in 2017, the Trump administration dramatically changed Barack Obama’s peaceful coexistence with Cuba and Venezuela. Where Obama initiated modest personal sanctions against perpetrators of human rights violations, US President Donald Trump doubled down, expanding the range of personal sanctions and initiating financial sanctions against the Maduro administration and PDVSA, Venezuela’s state oil company.

Year after year, the sanctions have grown in scope and depth, until recently putting into effect what amounts to an oil embargo. In recent weeks, three additional moves have put greater pressure on Venezuela’s regime. The first was the indictment of Maduro and his closest allies for narcoterrorism, setting a price on the heads of a selected number of them. The second was the mobilization of a fleet to the Caribbean to allegedly stop narcotics trade directly (but indirectly to put military pressure on Venezuela). The third was sending an olive branch that allows for the creation of a transitional government in the country where Chavismo would participate and the high command of the armed forces respected.

The Coronavirus and Other Urgencies

One of the preferred arguments of the anti-sanction analysts has been that contrary to their purported goals of cracking the regime, what sanctions have achieved is the circling of the wagons around Maduro and the core elite. This may have been true so far, but there is no evidence that other strategies to bring them to the negotiating table have worked either. Nor has there been a minimal political will within the Maduro regime to correct course, allowing Venezuela to turn back to democracy and a less traumatic economic experience.

That was the case of other countries of the so-called “Pink Wave” in Latin America, like Bolivia, Ecuador in the times of Rafael Correa or even Nicaragua. This stance against sanctions and other strong measures has gained new credence in the midst of a crisis caused by the novel coronavirus, known as COVID-19. Why torment Venezuelans even more, they seem to claim? What these late new measures risk is creating a horrendous sanitary situation, given the weakness of the health system in the country.

At first sight, these arguments seem commonsense. But at a closer look, they suggest substantial inconsistencies. Take COVID-19. For reasons that are still unknown, Mother Nature has been very benevolent with Venezuela regarding the impact of the coronavirus. So far, both the number of people infected and the resulting deaths have been very low. But as most experts claim, Venezuela may not fall prey to the pandemic in this first stage, but there is no guarantee that it may not succumb during another wave, mainly because there will be no means to immunize the population at large. Sooner or later, the country has to be prepared for an outbreak. What are then the odds that Venezuela will continue faring well?

One first aspect is the regime’s capacity to overcome the shortages of the health system because, after all, it would be responsible for responding to an impending massive outbreak of the virus. Most experts, even those opposed to sanctions and other forms of pressure, agree that the health system in Venezuela is in dire straits. Not only has the primary care network developed by Chavez in his golden era collapsed, but the public hospitals and even private ones are in no condition to face the normal handling of public health, much less an epidemic.

It is not only the shortages in the specific requirements to face the epidemic, but even more critical ones: lack of running water, continuous electricity failures, and acute shortages of antibiotics and even alcohol and other minimal requirements for emergency room attention. If the regime has failed to reverse or even face these disturbing conditions in the last few years, why would it do it better now? Moreover, there is a lack of doctors, nurses and other paramedic personnel, many of whom have engrossed the diaspora. Clearly, the regime would be unable to bring them back on short notice, but an appeal by a transitional government might recruit greater numbers.

Another element to bear in mind is that imports of food and medicines are not included in the US sanctions. The Maduro administration has been freely importing food from Mexico and Colombia for its controlled handling of food packages and medicines. The only restriction is the volume of money the regime has been willing to disburse (or at its disposal) for greater levels of imports. And, of course, the latter question is directly related to the collapse of the Venezuelan economy, which has been pushed by Maduro to a continuous free fall for the last six years.

Another crucial factor of the current situation affecting not only the health system but the country as a whole is the shortage of gasoline. The current gasoline deficit is leading to a near collapse of agriculture, industry, public transportation and the rest of transportation requirements. In itself, it could bring about a total collapse of production and potentially a famine. Combined with a COVID-19 epidemic, the horror could be beyond description.

So far, the sanctions have impacted imports of gasoline, but the question to be asked is: Why, after having one of the world’s largest and more modern systems to produce gasoline, has Venezuela had to import almost all the gasoline it consumes? When Chavez came to power in 1999, Venezuela had the capacity to refine around 1.3 million barrels of oil a day mostly into gasoline, gas oil and other products in three giant refineries. Roughly 60% of that capacity was for the internal market and the rest was exported worldwide. Today, the percentage of that capacity that is utilized amounts to only around 3%, which only covers a minimal fraction of the internal market. As a result, Venezuela has to import most of its gasoline and gas oil requirements.

Paradoxically, even in this critical situation, while Venezuelans wait in line sometimes for three days to fill up their tanks, Maduro is sending Cuba a continuous flow of barrels of gas oil and other derivatives. Only in the last few weeks did it send from Amuay (a refinery that is still open) 72,000 barrels, which added to another three tankers, to bring the number of refined products to 422,000 barrels, not including 400,000 additional barrels of crude oil sent to a refinery in Cienfuegos, Cuba, to be processed there. This does not take into consideration the number of barrels of gasoline that are smuggled daily to Colombia thanks to the huge price differential between the two countries (most of which is allegedly controlled by the national guard).

So, again, the question to be asked is: What real advantages to everyday Venezuelans will levying the oil sanctions provide? Will refining capacity be restored? Will the huge distortions that the current subsidies entail disappear? Will gasoline shipments to Cuba be rationalized and sold at a fair price, or smuggling duly stopped?

The Path Forward

What lies ahead? Either Maduro finds his way to continue holding to power, in which case the country will continue its free fall, or a transition allows Venezuela a return to relative economic normalcy and to democratic rule. It is not clear which path will prevail, but if change occurs, in all probability utmost pressure would have made the difference.

At the moment, the regime has been losing its grip on the country as a result of the collapse of the oil industry, mostly self-inflicted. It is not only the production of gasoline that is in dire straits. Venezuela has reached the lowest level (around 600,000 barrels a day) of oil production in a long time, only comparable with production levels around 1941. And there are reports almost every day of fires in many oil settings, due to sheer incompetence and lack of maintenance, or simply the abandonment of oil rigs that until recently were active.

There is, of course, no guarantee that there will be internal cracks in the ruling coalition, but never has the regime been as weak as it is now. It is feeling the pressure (especially external) like never before and, different from other junctures, there is wariness among its ranks that it may not be able to resist. There were recent reports that Maduro attempted a direct channel of negotiations with the Trump administration. Even if there are no clear signs of what Maduro wanted, immediately, the US State Department declared that there would be no direct dealing with the Venezuelan leader and that any new option to be discussed required that Maduro abandon power.

It is hard to anticipate who within the current ruling elite might be willing to yield and open a window for a transition. So far, they have held tight as a team, except in the March 30, 2019, episode where profuse reports indicated that several top members of the coalition considered entering a transition. As we know, it never happened. But at the time there were some indications that this group — which included Vladimir Padrino Lopez, the current minister of defense; Maikel Moreno, the head of the supreme justice tribunal; and other military officers — was ready to abandon Maduro.

Most of these officials have been currently targeted by the US Justice Department, so they are under direct pressure. So too is Maduro himself, as well as Diosdado Cabello, second in command and head of the PSUV (the ruling government’s party), and Tareck El Aissami, former executive vice president of Venezuela and currently minister of industry and national production. It is not an exaggeration to say that the current power lies to a great extent in these latter three leaders.

In any case, abandoning sanctions to weather the coronavirus pandemic is not an option, given the disastrous conditions that the regime has created in all areas: the health system, especially hospitals and personnel; the collapse of production; acute gasoline shortages; and the total centralization of food distribution under the command of the government. Levying gasoline embargo would only help to refresh the regime’s coffers, but with no guarantee that new imports would be directed to transportation needs and not to smuggling to Colombia or exports to Cuba.

The same goes for the health system. The likelihood of new loans or other means of financial flows to be directed to strengthening hospital capacities, reinforcing the testing means or allowing for increasing the number of beds for hospitalization in the event of a steeper breakout of the epidemic is very low. If it has not happened until now, why should all of a sudden the regime reveal itself as a humanitarian warrior?

The best chance Venezuela has to avoid a humanitarian disaster, resulting from an impending famine and an expansion of the coronavirus crisis to very high levels, is to force a change in the current ruling of the country.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.