The new president must choose between respecting the independence of Colombia’s judiciary and standing by the innocence of his political mentor.

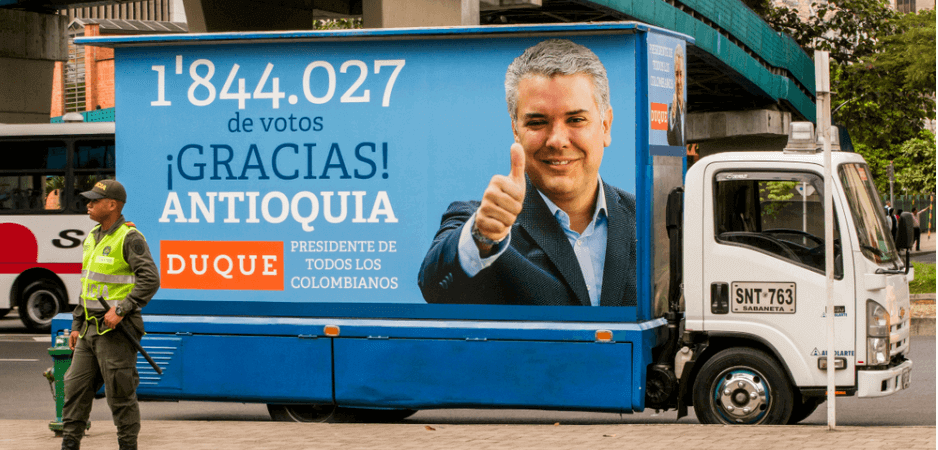

The inauguration of Ivan Duque as Colombia’s new president took place on August 7, on what was an extremely windy afternoon in the capital city of Bogotá. The inclement weather seemed fitting given the current political climate. Duque’s swearing in ceremony marks the rise to power of the Democratic Center — until now a major opposition party. During the ceremony, the head of Colombia’s senate and one of the most radical members of the Democratic Center, Ernesto Macias, delivered a fiery speech that lauded the party’s founder, former President Alvaro Uribe, and accused the outgoing president, Juan Manuel Santos, of leaving behind a country overrun by criminal groups.

This polarizing episode, which featured chants of “Uribe, Uribe!” and a standing ovation to the former president, comes on the heels of a quickly unraveling political saga. On Friday, July 20, new members of congress took their seats, including, for the first time in the country’s history, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) in the form of five senators and five representatives under the newly created Common Alternative Revolutionary Force (also FARC).

However, the new president’s troubles do not stem from his political archenemies. Rather, pressure comes from within his own party ranks, whose members are openly attacking the independence and legitimacy of the country’s judicial branch.

Bombshell Accusations

On July 24, Colombia’s political scene was shaken by the announcement that former president and current senator, Alvaro Uribe, was being summoned by the country’s supreme court to answer questions on witness tampering and bribery charges. Specifically, Uribe and fellow congressman Alvaro Hernan Prada are being accused of bribing several individuals, particularly a current inmate in Colombia’s prison system, in order to extract exculpatory statements before a court. The main witness in question is Juan Guillermo Monsalve, who had previously testified alongside one of Uribe’s main political enemies, Senator Ivan Cepeda, against the former president and his brother, Santiago Uribe, on charges of paramilitary activity.

For years, Uribe’s inner circle has been entangled in a web of judicial proceedings, focused mostly around his brother, who is currently in the middle of trial for his alleged leadership role in a paramilitary death squad known as the Twelve Apostles. However, before July 24, Alvaro Uribe himself had never personally been targeted in such a serious and damning way.

The bombshell accusations against Colombia’s most powerful man who has ushered his anointed protégé, Ivan Duque, to the country’s presidency, even led Uribe to initially submit a resignation letter from his post in the senate (which he subsequently withdrew on August 1) — a dramatic step given that he won more votes than any other senate candidate in the country.

Simultaneously, over the last two weeks, Uribe and his lawyers have led an all-out media offensive claiming that the charges against him are part of a political hit job orchestrated by political enemies. The gravity of the accusations against Uribe put President Duque in a serious bind. The new president, who tried to strike a conciliatory tone during his inaugural speech, must choose between respecting the independence of Colombia’s judiciary and standing by the innocence of his political mentor (whom Duque has defended for years). Thus, Duque’s actions over the coming weeks could drive a wedge between himself and his long-time political mentor.

If Duque were to break with Uribe, the former president’s allies like Ernest Macias would take this as an unforgivable political betrayal. This was already the case with President Santos, after his election under the Uribe banner in 2010. Santos, who broke with Uribe over the peace talks with the FARC rebels, was able to survive this political breakup with his predecessor and the country’s right-wing political base.

But he paid dearly for this rift during the 2016 referendum on the FARC peace deal, which was narrowly defeated thanks in large part to right-wing opposition. Moreover, as Macias’ speech on August 7 demonstrated, Democratic Center loyalists will never forgive Santos and will always stand by Uribe. Walking away from Uribe would present similar challenges for Duque because he would lose the support of Uribe’s Democratic Center, which was founded in 2013 by the former president as an opposition to Santos. Even if all the other parties within Duque’s congressional coalition remained loyal to him, his majority would be substantially slimmer without the Democratic Center, making it much more difficult to enact his domestic agenda. Most importantly, by turning his back on Uribe, Duque would draw ire from the base that elected him under the banner of the Democratic Center.

A Degree of Independence

Conversely, walking away from Uribe could also give Duque a degree of independence that he has never before enjoyed as a politician. President Duque could distance himself from his warmongering mentor and announce that he will not seek to alter the Havana peace accord that the Democratic Center had previously threatened to tear to shreds. Duque could pursue a moderate political agenda that would be welcomed by many, maybe even some skeptics within the political ranks of the FARC.

The new president’s first step in demonstrating his independence could be to ask congress to stop limiting the power of the Special Jurisdiction for Peace, which was set up as a key mechanism of the FARC peace deal to process criminal charges against former combatants using a reduced sentencing scheme. Such a position would certainly face pushback from some major parties within Duque’s congressional coalition, especially among Uribe allies, while it would likely be supported by a large number of center-left parties.

If President Santos was able to win over the minds and hearts of moderate Colombians by sliding toward the center and pursuing an uphill battle for peace, President Duque could also win over a centrist base by protecting the FARC peace deal at the expense of his more right-wing political base.

Over the coming weeks, Duque will have to choose a path, and his choice will send a clear signal on whether Uribe will survive this latest political storm. Meanwhile, if Uribe overcomes the judicial and political challenge before him, he will likely remain the most powerful figure in Colombia for years to come. However, if he is found guilty and has to serve any type of sentence, it would mark a new era for Colombian politics and for the country’s social fabric.

Duque will need to prepare for both eventualities and faces a difficult decision. In the meantime, the leaders of the Colombian opposition would be wise to maintain open dialogue with the incoming president, making it clear that there is an alternative to Uribe, should the new president decide to turn his back on him. Duque, much like his country, finds himself at an important crossroads and must seriously ponder a future without Alvaro Uribe.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Photo Credit: pppp1991 / Shutterstock.com

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 3,000+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Commenting Guidelines

Please read our commenting guidelines before commenting.

1. Be Respectful: Please be polite to the author. Avoid hostility. The whole point of Fair Observer is openness to different perspectives from perspectives from around the world.

2. Comment Thoughtfully: Please be relevant and constructive. We do not allow personal attacks, disinformation or trolling. We will remove hate speech or incitement.

3. Contribute Usefully: Add something of value — a point of view, an argument, a personal experience or a relevant link if you are citing statistics and key facts.

Please agree to the guidelines before proceeding.