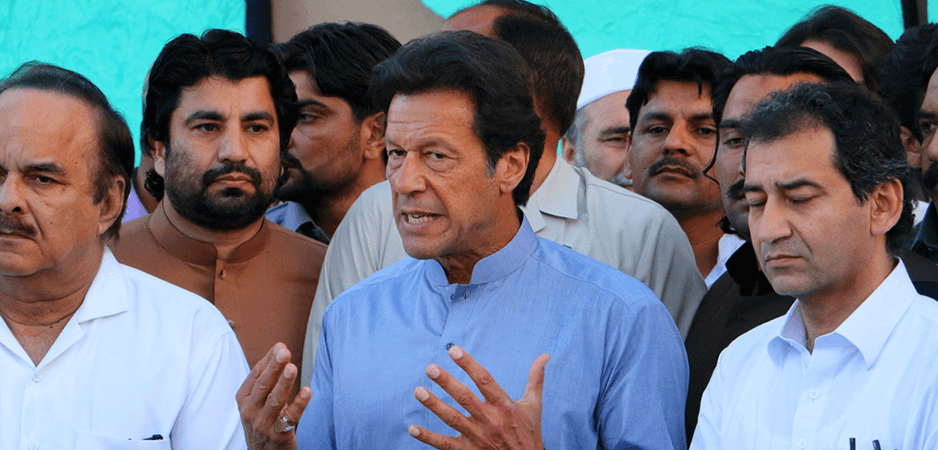

Pakistan has a new prime minister-in-waiting, Imran Khan. Does China see him as a friend?

Imran Khan’s ability to chart his own course, as well as his relationship with Pakistan’s powerful military, is likely to be tested the moment he walks into the prime minister’s office. Pakistan’s most fundamental problems loom large and are likely to demand his immediate attention.

Khan will probably have to turn to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for a $12 billion bailout to resolve Pakistan’s financial and economic crisis. The request could muddy his already ambiguous relationship with China. The IMF is likely to reinforce Khan’s call for greater transparency regarding the terms and funding of projects related to the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), a crown jewel of Beijing’s Belt and Road initiative and — at more than $50 billion — its single largest investment.

Crack Down

Khan’s need for a bailout is likely to give him little choice but to crack down on militant groups that have enjoyed tacit, if not overt, support of the military.

To be sure, Khan could evade resorting to the IMF if China continues to bailout Pakistan as it has done in the past year with some $5 billion in loans. Alternatively, Saudi Arabia could defer payments for oil that account for one-third of Pakistan’s petroleum imports as it did in 1998 and 2008. Continued Chinese assistance or Saudi help would provide immediate relief. But without a straightjacket forcing Pakistan to embark on painful reforms, this would do little to resolve the country’s structural problem.

An IMF straightjacket, however, may solve one Chinese dilemma: backing for the Pakistani military’s selective support for militants. China’s support was in response to a request by the military, as well as the fact that militants focusing on India and Kashmir granted Beijing useful leverage.

China, nonetheless, has hinted several times in the past two years that it is increasingly uneasy about the policy. It did so, among others, by not stopping the Financial Action Task Force — an international anti-money laundering and terrorism finance watchdog — from putting Pakistan on a gray list, with the threat of being blacklisted if it failed to agree and implement measures to counter money laundering and funding of militants.

CPEC

Chinese sensitivity about greater CPEC transparency was evident in Beijing’s attempts to stymie Khan’s criticism during the recent election campaign and when he was in opposition. Chinese pressure on Khan and his populist Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) to tone down their criticism produced only limited results, despite China’s expansion of CPEC’s master plan to include the prime minister-in waiting’s stronghold northwestern province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. The move, however, did not stop PTI activists from continuing to portray CPEC as a modern-day equivalent of the British East India Company, which dominated the Indian subcontinent in the 19th century.

PTI denounced Chinese-funded mass transit projects in three cities in Punjab — the stronghold of the party’s main rival, Pakistan Muslim League-N — as squandering of funds that could have better been invested in social spending. PTI activists suggested that the projects had involved corrupt practices. In 2017, China rejected allegations by Awami National League leader Sheikh Rasheed Ahmad, a Khan ally, of corruption in a Chinese-funded bus project in the city of Multan.

By Monday night I had done 60 different jalsas in the most difficult times under serious terrorist threats – esp in Bannu and Karak – and in the hottest weather. I want to thank the hundreds of thousands of people who came to these jalsas. pic.twitter.com/f9eu1AIhBh

— Imran Khan (@ImranKhanPTI) July 23, 2018

Pakistani officials said PTI critics would likely get their way if the country agrees with the IMF on a bailout. “Once the IMF looks at CPEC, they are certain to ask if Pakistan can afford such a large expenditure given our present economic outlook,” the Financial Times quoted a Pakistani official as saying. CPEC was but one of several issues that have troubled China’s attitude toward Khan, despite a post-election pledge to work with the prime minister-in waiting.

China was unhappy that a five-month anti-government sit-in in Islamabad in 2014 forced President Xi Jinping to delay by a year a planned visit, during which he had hoped to unveil a CPEC master plan. Pakistani security analyst and columnist Muhammed Amir Rana, just back from a visit to China, said Beijing was also uneasy about Khan’s plan to tap the expertise of Pakistan’s highly educated US and European diaspora, who could counter the PTI’s anti-US bent.

CPEC, and particularly ownership of projects related to the corridor, is likely to be one indication of Pakistan’s relationship with China under a PTI government, as well as the nature of Khan’s rapport with the military. The issue is sensitive, given expectations that Chinese investment is pushing Pakistan into a debt trap.

Rana noted that the Sharif government had resisted a military push for the creation of a separate CPEC authority. The military and the Sharif government were also at odds over the establishment of a special security force to protect Chinese nationals and investments that have been repeatedly targeted in Pakistan.

A Friend in Khan?

The Chinese Communist Party’s English-language media organ, Global Times, was quick to declare victory in the Pakistani election. While mentioning past Chinese concerns, the paper pointed to the fact that Khan had unveiled a plan to adopt the “Chinese model” to alleviate poverty.

Noting that China was the first country Khan mentioned in his first post-election speech, the Global Times gloated: “Despite a barrage of criticism he threw at Sharif’s handling of Chinese investments, Khan is not a skeptic of the projects themselves … Imran Khan minced no words when his exclusive interview was published in Guangming Daily two days before the elections. Khan asserted that the CPEC will receive wide support from all sectors of Pakistani society.”

In the same article, Daniel Hyatt, the author, added: “Imran Khan’s politico-economic views do not seem to be influenced by his Western education. He questions the practicality of capitalist economic policies. He is also a strong critic of US President Donald Trump, the US and US-led wars … Imran Khan’s plan is a clear pivot by Pakistan, away from the US orbit and further into the Chinese bloc … China has a friend in Imran Khan.”

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Photo Credit: Jahanzaib Naiyyer / Shutterstock.com

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.