The more inundated people are with misleading “facts,” the more questioning and distrustful they become. The effect this has on climate change leads to denial.

In my previous articles—Why Do Some People Reject Climate Change? and The Rejection of Climate Change—I explored a few reasons for the denial of climate change science. In this article, I explore one other.

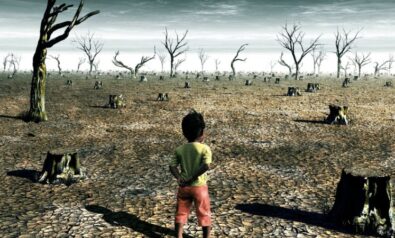

Despite the overwhelming scientific evidence of climate change and its effects, some people are still skeptical. While the number of skeptics may be diminishing, there are lessons we can learn from the failure to galvanize consensus and acceptance of the science and the resulting slow progress on global actions to tackle climate change and minimize its effects. These lessons may in future assist in dealing not only with climate change, but with other major global issues such as food and water shortage, mass migrations, Internet-related problems, child pornography, human trafficking and others requiring globally coordinated actions and agreements.

This is the third of a series of articles in which I explore some of the reasons for such skepticism by some.

Distrust of Authority and Climate Change Denial

Over the past few decades and increasingly as more information becomes freely available, the global community has been inundated with widely varying, usually conflicting and often misleading “facts.” As a result, we have all become more confused, more wary, more questioning and perhaps even distrustful of science and authority in general. As the world becomes more educated, more people are in a more knowledgeable and better informed position to ask questions and seek answers.

As there is always some uncertainty in most areas of science that the general public is in daily contact with, there is a tendency to question or at least seek clarification on matters relating to scientific findings and conclusions. As it is usually the exceptions that get reported, over time, there has been erosion of our unconditional trust or acceptance of science.

In addition, because of the allure of funds and financial gain in our lives, there has been the added conception or misconception that scientists, just like any other professional group, are vulnerable to financial and self-interest and, therefore, bias. Skeptics have suggested that at least some climate change scientists have vested interests or are likely to gain from assertions made by them.

Associated with a distrust of science are conspiracy theories. When the overwhelming body of scientific opinion believes something is true, the denialist will not recognize that a large number of scientists have independently studied the evidence to reach the same conclusion. Instead, they claim that scientists are engaged in a conspiracy. Similarly, there have been many accusations of medical practitioners being influenced by the pharmaceutical industry. The recent movement against vaccination has put children’s health at great risk.

Although not directly related to our distrust of science, or at least a lack of full trust of it, there are many other authorities that we have become increasingly less trustful of. These include governments, the police, clergy and religious institutions, and even the judiciary. Media outlets are full of daily reports of people in power—people in positions of trust being caught out for unethical, illegal or simply wrongful acts.

The potentially catastrophic projections and seemingly alarmist views on climate change also complicate the messages being conveyed to the general public. Many people and reporters in the denial camp argue that the projections are alarmist and are, therefore, unrealistic. It is only natural that if and when a projection is made which is so alarming and so disturbing, that it will be viewed to be exaggerated.

The predicament that climate change scientists have is this: Let’s say that their findings indicate a catastrophic outcome. If they report the catastrophic predictions, they will be seen to be scare-mongering and exaggerating. On the other hand, if they deliberately down-play the findings (so they are not accused of exaggeration), the public is likely to dismiss the findings as marginal or not urgent enough for radical and expensive action.

Yet another factor also associated with distrust of authority and hierarchical organizations in our society is what is known as anti-authoritarianism. This involves general opposition to any form of authority. The main conflict here is between obedience or subjection to authority and individual freedom and determination. Anti-authoritarians do not have to be extreme in the form of anarchism—an ideology that entails completely opposing authority or hierarchical organization in the conduct of human relations.

The real challenge in communicating the required messages is faced when one needs to make announcements or provide existing, well-established or new details of scientific knowledge on climate change.

Consider starting a sentence with, “The science on climate change is telling us that …” Would that work? I don’t think so, because as explained above, there is already considerable distrust or at least some cynicism toward science. We could use, “Scientists are now telling us that …” Would that work? Unlikely, as those who have some doubts as to the reliability of scientific knowledge have an even higher level of distrust on scientists usually because it is believed that scientists, as individuals, have or can have vested interests such as vying for funds for research. So, how else could be begin such a sentence? How about, “Experts are telling us that …”?

Media Reporting

Distrust of science and authority in general is a complex societal issue. A major contributor to our increasing tendency to distrust or reject what scientists or experts or authorities tell us is the constant media reporting of exceptions, frauds and failures. Every day, in the media, there is a regular barrage of news of failures and mistakes made by science, authorities and even experts. The financial system led the world down in the global financial crisis; numerous religious groups have been found to have abused their trust in looking after young children; politicians throughout the world have been found to have abused their position of power.

Associated with a distrust of science are conspiracy theories. When the overwhelming body of scientific opinion believes something is true, the denialist will not recognize that a large number of scientists have independently studied the evidence to reach the same conclusion.

We don’t have news that says, “This week, hundreds of thousands of surgical operations throughout the Western world saved the lives of sick people.” Instead, we hear that, “This afternoon, a woman was misdiagnosed for appendicitis in a local hospital.” As if that’s not enough, the next day, there’s a follow up comment or opinion by an “expert” who says that this event is “not an isolated case” and that “it happens regularly.”

What this leads to is a tendency for all of us to listen to the experts or authorities, consider their reasoning, empirical justifications and conclusions, and then make up our own minds as to whether we accept their judgments or conclusions. Depending on the complexity of the issue, we may listen to a number of experts or authorities and then make up our own mind as to which of them we accept or believe.

One of the interesting aspects of such behavior is how we choose which of the experts’ views we accept. As explained in an earlier article on confirmation bias, our choice is not always based on reason or logic and can ironically be itself biased. Ironic because one of the reasons we often reject an expert’s opinion or conclusion is that it is deemed to be biased. And this usually leads to making adjustments to an expert’s advice.

A common tendency, for example, is the choice of some aspects of science and the rejection of others. So, through confirmation bias, we pick and choose experts and also which part of their advice we accept. We might go to our doctor to get advice on our illness and choose which part of the doctor’s advice we heed. So we might take the medication prescribed, but choose not to go ahead with surgery, even though we are told that surgical intervention will provide the best outcome and long-term solution.

We have all become—perhaps with some justification, and to some degree—anti-authoritarian and this may be a healthy tendency in democracies. However, when such tendencies spread to global issues such as climate change, they may result in considerable hardship for certain groups, certain countries and future generations.

These are only some of the reasons for climate change denial. In the next article of this series, I will explore other reasons for people who find it difficult to accept climate change science.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Photo Credit: Stockmdm / Frederic Legrand – COMEO / Shutterstock.com

We bring you perspectives from around the world. Help us to inform and educate. Your donation is tax-deductible. Join over 400 people to become a donor or you could choose to be a sponsor.

We bring you perspectives from around the world. Help us to inform and educate. Your donation is tax-deductible. Join over 400 people to become a donor or you could choose to be a sponsor.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.