America is a society openly experiencing a minority-majority shift.

If you ever spent an extensive period of time in the United States, you would agree that race is the most intractable topic in public conversation. Let’s face it, the nation’s mysterious past and current track record on race relations makes for an uncomfortable conversation. The US is a nation comprised of Native Americans, descendants of explorers, European immigrants, African slaves, and the countless millions who arrive yearly at its shores in search of the American Dream. To say the least, America is a tortured mosaic pavement slowly transforming into a multiracial hue.

As America commemorates the 50th Anniversary of the 1963 March on Washington that subsequently led to the Civil Rights Act in 1964 and Voting Rights Act in 1965, it is evident that five decades later a serious conversation on race and public policy is of critical importance. But the inability of Americans to objectively navigate a conversation on race without encountering “hiccups,” drives some to retreat or openly deny that racism exists. The reality is clear: Deep-seated fear and structural problems are present at both the national and individual levels, thus driving racial bias in public policymaking. In dealing with these structural problems, some choose to retreat to homogenous safe-ground, while others move beyond reservation to embrace cross-cultural engagement for the good of the society.

What is at stake on the question of race in America is the reality that covered wounds will soon be exposed and the national conversation to offer understanding might, in fact, achieve its goal. Speaking to this reality, some are only now coming to terms with the fact that it is nearly impossible to teach racism with authority when American children are more connected across cultural-lines today than ever before. These and other uncomfortable accounts are emerging as the nation moves toward the Brookings Institute’s 2043 projection of a minority-majority shift — a period when the US minority population is set to outnumber its current white majority. Amid this transition, Americans must welcome both the comfort that peace will bring and the reality that historical pain causes.

Understanding Historical Pain

For example, millions of Americans across a diverse spectrum of race and socioeconomic status displayed their contempt recently toward Florida’s Stand-Your-Ground law. The legislation, recognized today in nearly two dozen states, led to the senseless murder of an unarmed teen, Trayvon Martin, by George Zimmerman last summer. Both Martin’s death and the Zimmerman “not guilty” verdict of second-degree murder or manslaughter have further polarized the nation along the line of race, launching a much needed public discourse on race in America.

While people of color in the US are familiar with the unease of sharing public space, justifying one’s presence in this space borders on discomfort and humiliation. For African Americans especially, the State of Florida vs. George Zimmerman is reminiscent of several racially charged cases tried throughout the rural south during the era of Jim Crow, yielding neither a solid conviction nor justice. The murder of Emmet Till (Mississippi, 1955) and the 16th Avenue Street Baptist Church bombing (Birmingham, 1963, massacring four girls) have prompted individuals to recall episodes of insensitivity that left African American children devalued and exposed by the hands of southern racists. Such reminders amplify historical pain that is collected and transferred between generations, thus shedding light on the growing dismay African Americans have toward the US criminal justice system.

If an individual lives in a race neutral comfort zone, it is only natural they will assume the US is, in fact, post-racial or race is a moot factor in public policy. Confronted with reality, immigrants and people of color in America, living under or at the color-line, have the unfortunate luxury of being confronted with this bold and uncomfortable wrinkle that is directly linked to a racial past, yielding horrific social accounts and prejudicial decisions.

But how might a nation steeped in a history of discrimination and historical pain carve out a respectable public conversation?

Setting the Stage

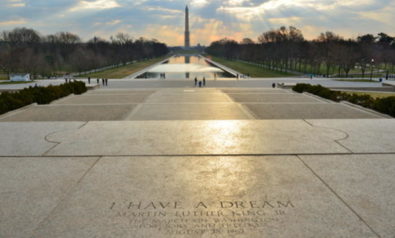

As tens of thousands of Americans of diverse backgrounds convene on the National Mall to bring awareness to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr’s “I Have a Dream” message and call for jobs and freedom, it is critical that the nation’s elected officials remember that silence toward suffering inflicted by racism threatens the civility of every individual living within the nation state.

Acknowledging this sentiment, US President Barack Obama was correct in stepping out front in July to give what could be his most provocative testimony on American race relations since assuming office. Openly admitting to being himself racially profiled, the president made an attempt to shed light on his personal narrative and explain the very root of historical pain and inescapable experiences incurred by African Americans in particular.

“There are very few African American men in this country who haven't had the experience of being followed when they were shopping in a department store. That includes me. There are very few African American men who haven't had the experience of walking across the street and hearing the locks click on the doors of cars. That happens to me — at least before I was a senator. There are very few African Americans who haven't had the experience of getting on an elevator and a woman clutching her purse nervously and holding her breath until she had a chance to get off. That happens often.” (link)

This enigma calls into question the very reason civil rights organizations, celebrities, athletes, interfaith practitioners, and civic leaders must divert from reservation to bring awareness to the nation’s rawest public conversation.

Three Steps in Moving Forward

What needs to be processed and honestly comprehended is the fact that America is not a race neutral society; it is a society openly experiencing a minority-majority shift. As this shift occurs, it will be to the advantage of all Americans to seek out common ground, in order to build equitable relations that seek to heal historical pain and the social frustration experienced by people of color in America.

Therefore, three key points should be considered when approaching this national conversation.

First, a national conversation on race beginning with the individual: While President Obama has cracked this sensitive discussion, the nation will find that people-to-people dialogue will hold significant weight in building tolerance. This conversation should not be forced; it should work to offer a safe-space to individuals willing to exercise mutual understanding. With America’s minority-majority shift underway, this conversation can, in fact, work to advance a more racially tolerant society.

Second, a national conversation at home and abroad to gather solutions on how to better deal with the question of race in America: Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr’s teachings on living within the “Beloved Community” speaks to how Americans must operate in the New America. When looking abroad, value is uncovered in the work of the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission and the legacy of former South African president, Nelson Mandela. Both offer clear insight into rebuilding a racially complex society marred by bias and discrimination.

Third, a national conversation seriously assessing why cultural frustration drives racially-bias policymaking: President Obama’s ascension into office unleashed a conservative backlash of reactionary legislation driven by race and social fear. It is essential Americans grasp why gutting the Voting Rights Act, Stop-Question-and-Frisk, derailing Affirmative Action in higher education, Stand-Your-Ground laws, and mandatory minimum sentences for black and brown citizens cut against American civility, stoking further the flame of racial discord. Civic discourse on race and public policy centering on these core pieces of legislation will offer new solutions for building a more evenhanded society.

The facts are clear: This new call to civic engagement demands speaking with candor about building a sustainable multiracial society at both the personal and national levels from parent to child, minister to congregation, and civic leader to policymakers. Securing a path that leads to the New America demands standing with conviction in the face of reservation.

The views expressed in this article are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Image: Copyright © Shutterstock. All Rights Reserved

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment