The imminent expulsion from Pakistan is threatening to push millions of Afghan refugees into deeper turmoil.

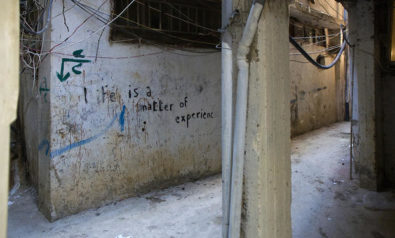

In a little over a week, a population the size of Equatorial Guinea strewn in the shadow of Hindu Kush mountain range will be forced to move abode. The mass mobilization will see nearly 1.6 million people, most of whom have lived in sprawling canvas-tent clusters for nearly three decades in extreme squalor, uproot their lives in pursuit of a new home. There is, however, one problem. They do not have a country to go to; not yet.

A lugubrious future is staring right in the face of thousands of Afghan families living in refugee camps dotting the northwest Pakistan. They have until midnight on June 30, 2013, to return to Afghanistan or find a new home, or otherwise risk detention and deportation by the Pakistani government, which last year decided to refuse visa extension to all foreigners on its soil including longtime Afghan residents.

According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), Pakistan is home to the largest number of refugees in the world followed by Iran and Germany. Most of the refugees are from neighboring Afghanistan — precisely 2.6 million of whom only 1.6 million are legally registered. Predominantly of Pashtun ethnicity, the refugees have been housed in nearly a 100 camps, the majority of which are based in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and tribal areas.

For most refugees, the imminent expulsion from their adopted home couldn’t come at a worse time. Questions over Afghanistan’s future, security, and political stability are becoming increasingly thorny, even as the US-led coalition forces prepare for their scheduled withdrawal next year following 13 years of military campaign in the war-ravaged country.

The Dichotomy of Dread and Desolation

The choice between repatriation to their home country, where peace is precariously fragile at best, and living in hiding or on the run as an illegal immigrant is a brutal one. A substantial number of Afghans have sought refuge in Pakistan since 1978, when the first tremors of political instability began to wreck their country following a bloody coup. However, it was not until the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan a year later that a tidal wave of refugees began to sweep the region as millions of Afghans fled fierce fighting and retribution. According to a European Commission report, nearly 3.7 million refugees had fled to Iran and Pakistan by the beginning of 1981.

The following two decades wrought even more havoc, displacing over a million people in Afghanistan. The mass exodus in the 1990s was a result of bloody conflicts among unrelenting Mujahideen factions wrestling for control over Kabul and later the brutal Taliban regime ruling the country with an iron-fist. The following decade began with a final wave of up to 300,000 refugees seeking safe sanctuary in Pakistan, in order to flee the US-led invasion of Afghanistan following the 9/11 attacks.

According to the UNHCR, despite incessant fighting and uncertain future, more than 5.7 million Afghans returned home in the past decade. In 2012 alone, nearly 89,000 left Pakistan to start life anew. But for under three million Afghan refugees, both legal and undocumented, the forced decision to leave Pakistan is still fraught with peril, and one that threatens to wreck their lives beyond redemption. Even though life as a refugee on perennial handouts has exacted a huge price on them, 80% of the remaining refugees have been living in Pakistan for over 20 years and have never left the safety of their camps. While 50% of the refugees were born in exile and have never seen their homeland, many others have tried to take roots in the host society through marriage and occupation.

However, their rights as residents are limited and basic freedoms and movement restricted. According to the UNHCR, most Afghan refugees continue to live in abject poverty. Less than 25% of them are employed and almost three quarters of refugee children do not attend school. The generations born in exile have had fewer opportunities in jobs and have long complained of harassment by the police and local authorities.

The Pakistani government, on the other hand, has over the years increasingly expressed concerns over lost economic revenue and the law and order situation in areas housing refugee camps. More significantly, the authorities have claimed that the treacherous tribal belt housing many camps was being used as a staging area for militant activity, a significant part of which was directed at Pakistani security forces amid rising radicalism.

In spite of a difficult life, it may not be hard to comprehend why thousands of Afghan refugee families have still chosen to stay on in Pakistan. According to a United Nations survey, 80% of the refugees do not wish to go back to Afghanistan. Many believe the help and assistance received through local social services and international organisations such as the UNHCR, however scant or rationed, will be hard to replicate in Afghanistan. But for most, the lack of economic opportunities and uncertainty shrouding Afghanistan’s future following the withdrawal of foreign troops in 2014, remain the ultimate obstacle to their return home.

Corruption is rife in Afghanistan and national institutions remain weak. Most of the refugees no longer have any skills and those who can farm do not have lands to build their lives anew. But most importantly, a large number of refugees remain skeptical of Afghanistan’s fragile political and security apparatus and fear that the US-pullout will spark a fierce power struggle. According to them, Afghanistan remains vulnerable to warring factionalism and tribalism – a debilitating weakness that will most likely be exploited by the Taliban and other radical elements.

A Three-Way Crisis

Despite mounting international pressure, the Pakistani government has thus far resisted urgent calls to revise its policy over visa extensions. Experts are now warning that Pakistan’s refusal on the issue is likely to catalyze a large-scale humanitarian crisis in the region by displacing nearly three million people. They argue, such a move can threaten to destabilize Pakistan’s own territory, as those reluctant to return may go underground or seek sanctuary with the ethnic Pashtun tribes functioning independently in the treacherous belt straddling the border with Afghanistan. The hasty move is not only highly likely to strengthen insurgency in Pakistan; economically it may cause the government to spend more in beefing up security.

The UNHCR, on the other hand, argues Afghanistan is not prepared to receive such a huge influx of people, even as the security situation remains precarious ahead of the withdrawal by coalition troops next year.

But most importantly, the forced mass mobilization will not only uproot lives and tear families apart, the experts warn such a move will push Afghan refugees deeper into a life of exploitation, poverty, and conflict.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Image: Copyright © Shutterstock. All Rights Reserved

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment