As more and more journalists are being targeted for their professional activity, the concepts of media freedom and journalist safety deserve a closer look — from the relative comfort of Europe to the killing fields of Syria and beyond.

Background

When Judge Gurfein ruled in favour of the New York Times for its right to publish the Pentagon Papers, he concluded that “a cantankerous press, an obstinate press, a ubiquitous press must be suffered by those in authority in order to preserve the even greater values of freedom of expression and the right of the people to know”. Indeed, the notion of uninhibited media is so engrained in our perception of democracy, that it carries both a symbolic halo and a real power of a weapon against injustice, corruption and lies. But no power struggle is without casualties, and journalists worldwide are paying a high price for their right to speak the truth, becoming victims of intimidation, torture, imprisonment and murder.

In a December 2012 report, the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) concluded that the number of journalists jailed for their professional activities has reached the highest mark since surveys began in 1990. At the end of the year, 232 were held, compared to 179 in 2011. Turkey leads the league tables, with 49 jailed, beating the previous record-holder Iran, with 45. China is third, with 32, and cracks in the monolith of obedience are beginning to show as journalists at the Southern Weekly went on strike to protest against censorship. China joined Russia, Saudi Arabia, Sudan and United Arab Emirates in trying to lobby for even-more stringent internet control laws at the International Telecommunications Union (ITU) in Dubai, unsuccessfully.

In Britain, the idea of a free, boisterous press is part of the national ethos and has not been regulated by a statutory body since 1695. Yet, the exposure of Rupert Murdoch’s News of the World and other publications’ phone hacking surveillance practices, has led to a re-evaluation of the role of the media and what it is and isn’t allowed to do. The 18-month long Leveson Inquiry condemned the “culture of reckless and outrageous journalism”, and suggested establishing a new press regulator, which, if publications fail to comply voluntarily, will be enforced by law. The move provoked strong reactions from prominent human rights activists, the information commissioner and the prime minister.

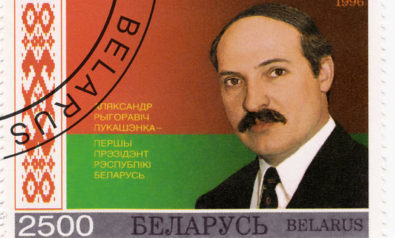

Elsewhere in Europe, Russia scored 80 points on the 2012 Freedom House survey, earning it a rating of “not free” and a 172nd place, which it shares with Zimbabwe and Azerbaijan. The state owns all six national TV networks, two of the 14 national newspapers, and 60% of the registered 45,000 local publications, as well as two national news agencies. The CPJ places Russia 4th in its list of deadliest countries, with 54 reporters murdered since 1992. As new laws are issued with increasing frequency in an attempt to curb dissent, Russia’s practices have been unfavourably compared to those of “Europe’s last dictator” Alexander Lukashenko of Belarus, responsible for a heavy crackdown on opposition, with an absurdist touch .

Pakistani media has evolved in recent years, from three state-run channels in 2000, to more than 89 today. The electronic media has, to a large extent, opened up the population to a diversity of voices and opinions, but also exposed journalists to regular threats, while the government has little power, or willingness, to protect them.

Press freedoms in Canada and the US are increasingly restricted, largely due to the monopolization of media outlets by the “Big Six”. The US ranked 47th in the Reporters Without Borders 2012 survey on press freedom — a significant drop from 17th place in 2002. Canada has a better track record than its southern neighbour, ranked 5th in 2002, and 10th in 2012. However, journalists working in Canada and the US struggle with similar issues: blocks to public information requests, politicians’ ability to circumvent right to information petitions, and government bans on reporting public court proceedings. The tenets found in the First Amendment in the US, and Section 2B of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, clearly need to be protected and upheld.

Since the Arab Uprisings, there has been a growing debate over press freedom and the direction the developing political systems are going to take. At present, however, in Egypt there has been criticism placed on President Mohammed Morsi and the new constitution as opponents argue it curbs press freedom. Likewise, in Tunisia there are opponents of the slow change. Many Arab and foreign journalists have died covering the uprisings, while the Syrian conflict continues to steadily claim lives.

Why is Media Freedom Relevant?

In writing about press freedom, the awareness that one is essentially writing in defence of one’s self is palpable. Yet, journalists must constantly question themselves in order to earn the right of their place in society. They also deserve the right to do their job without fear of being tortured, or seeing their loved ones threatened, or killed. Journalistic safety means a lot more than protecting people from being targeted in war zones — a new, unwelcome development of the Iraq war. When journalists are targeted by either the government or the criminal organisations, or both (Mexico), self-censorship becomes the norm and fear takes the place of journalistic ethics. Free press, where it exists, is an institution that needs to be defended and – where it is comprised of only a few dedicated upholders – needs to be fostered, in order to protect opportunities for debate, change and justice.

Image: Copyright © Shutterstock. All Rights Reserved

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a sustaining member.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.