While Turkey argues that it has the capacity to address the increasing flow of Syrian refugees, several refugee advocacy groups have criticized Turkey’s policies and have called on Ankara to adhere to its obligations under international law.

As the international community is struggling to find a solution to end the violence in Syria, the humanitarian situation inside the country continues to deteriorate. The fighting has already cost over 19,000 lives, as dozens continue to be killed on a daily basis. According to the most recent United Nations estimates, between 1 and 1.5 million people are in urgent need of humanitarian aid. The UN Refugee agency, the UNHCR, recently announced that nearly 120,000 displaced Syrians are registered as refugees in Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey, while the number of Syrians arriving in Turkey alone rose by a staggering 44% in the past six weeks.

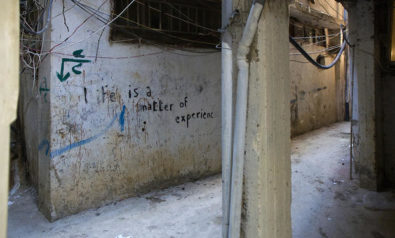

Refugees in Turkey

Turkey’s position in the Syrian crisis is unique due to a number of reasons. It is a member of NATO and shares a 900-km land border with Syria. The number of high ranking Syrian officers who are defecting and seeking sanctuary in Turkey has also increased in the past few weeks. After last month’s downing of a Turkish military jet by the Syrian military, Ankara toughened its stance against Damascus and deployed armored vehicles and air defense systems on the Syrian border. While these stories dominate the headlines, an often sidelined but equally important issue has been the safety and status of Syrian refugees in Turkey.

Since the crisis began, Turkey has kept its borders open to displaced Syrians fleeing the turmoil. In fact, the Turkish Red Crescent (TRC) was quick to respond to accommodate incoming Syrians and set up camps in the border province of Hatay following the first arrivals in March 2011. The Turkish government has tasked the country’s disaster and emergency management administration, the AFAD, with administering Syrian refugee operations, and has entrusted the TRC with running the camps.

According to the AFAD, all types of humanitarian relief for Syrian “citizens” (the Turkish government does not use the term “refugee” to refer to displaced Syrians) are provided. International observers and media confirm that Turkey’s “tent cities” are well-equipped and able to provide the basic needs of Syrian refugees. Currently, Turkey manages the refugee operations by itself and the UN provides assistance and advice only upon request by Turkish officials. Ankara says it will only ask the UN for assistance if the number of refugees exceeds the country’s capacity to respond. The government, however, has not yet defined what constitutes this capacity or limitations to its emergency response capacity.

The latest numbers provided by the UNHCR indicate that more than 40,000 Syrians are currently being sheltered in seven camps established by the AFAD. Although Turkey shares a large border with Syria, Turkey’s refugee camps are almost exclusively concentrated in Hatay, the main entry point for Syrians.

Temporary Protection, Long-Term Crisis

Notably, the international community has repeatedly welcomed the Turkish government’s efforts in helping the displaced Syrians since the crisis began. However, several international and national refugee advocacy groups recently issued statements criticizing the uncertainty concerning the status of refugees in Turkey and Ankara’s policy of not involving international organizations and NGOs in the process. Both issues are fundamentally linked to ensuring transparency and Turkey’s adherence to its obligations under international law.

As noted, Ankara does not officially use the term “refugee” to refer to displaced Syrians. In fact, when the crisis began, Syrian refugees were called “guests” by the Turkish authorities – a position that was seriously criticized by advocacy groups. The underlying problem here is that, even though Turkey is a signatory to the 1951 Refugee Convention, it imposes a geographic limitation exclusively for the European continent. Therefore, refugees from countries outside Europe are not entitled to obtain refugee status or to receive protection from the Turkish government. This policy creates uncertainty regarding the legal status and rights of more than 30,000 Syrians who are currently in Turkey.

After several international calls, Turkey finally decided in November 2011 to set up a “temporary protection” regime to clarify the status of Syrian refugees. According to the UNHCR, this regime ensures access to basic needs and is in line with protection principles such as admission to territory, protection against refoulement, and safe return to the country of origin when conditions permit. While this policy meets the minimum international standards and expectations of the international community, the regime itself has no legal basis in Turkey’s laws.

Amnesty International, for example, states: “While Amnesty International notes that the Turkish authorities have put in place a temporary protection regime, it is concerned that temporary protection may not be appropriate for those refugees who have long-term protection needs, and who will need and be entitled to durable solutions for their displacement… Amnesty International is concerned that a failure to identify individuals in need of long-term protection may put them at risk of refoulement in the medium to long term.”

Therefore, while the temporary protection regime offered to Syrian refugees is satisfactory in the short-term, it certainly is not a solution for a long-term emergency as the Syrian crisis. Although most of the Syrian refugees reported that they want to return once the conditions permit, some may not want (or may not be able) to return to their home country. According to a report by the Council of Europe (CoE), only a few Syrians applied for asylum since the crisis began. This may be due to the complex asylum process and the lack of information provided by Turkish authorities during the registration. Therefore, the CoE asked Turkey to improve the current registration of refugees by recording not only the reasons for their arrival but also the reasons for their return in order to monitor the situation more effectively.

Lack of Transparency and Limited Media Access

Several advocacy groups have also criticized Turkey’s continued reluctance to involve international and national NGOs and international organizations in the process. Ankara’s position regarding NGOs raises concerns of transparency and third-party oversight on practices in the refugee camps. As the CoE report underlines, although a small number of international and national delegations have visited Hatay, almost none have been given permission to enter the camps. In fact, Ankara turned down numerous calls from international and national NGOs offering to contribute to the process or asking to observe the operations in the camps. Even the media often finds it difficult to access the camps and contact refugees.

Considering the allegations concerning the camps in Turkey, it is crucial that Ankara involves NGOs in refugee operations. Last February, a Turkish daily reported allegations about refoulement of high profile Syrian dissidents, which is a violation of the non-refoulement principle of the international law forbidding rendering victims of persecution. Another article reported the existence of a special camp for Syrians with “problematic backgrounds,” which is allegedly being used as a center for forced returns. While Ankara has denied the validity of both reports, without independent NGOs and advocacy groups watching over practices in the camps, violations may indeed occur. Turkey’s decision to keep the camps under exclusive control of its own agencies, therefore, hinders Turkey’s obligations under international law.

Several Turkish organizations have already contacted Ankara regarding access to camps. The Coordination for Refugee Rights in Turkey (CRR) and Refugee Rights Association (Mülteci-Der) have made several attempts to reach out to related government agencies regarding the legal uncertainties of the temporary protection regime and the issues of camp access and transparency. Similarly, Amnesty International has sent four letters to the Turkish Foreign Ministry since October 2011, requesting assistance to access the camps, but has not received permission.

Proper registration and processing of refugees is of crucial importance in times of emergencies.Both the CoE and Amnesty International requested that Turkey enhance and improve monitoring, screening, and registration of new Syrian refugees. In Turkey, however, key organizations such as the UNHCR and the International Organization for Migration (IOM) do not fully participate in these areas. These organizations have experienced staff that are trained to work in emergencies and can contribute. Yet, the UNHCR Turkey has only recently set up a permanent office in Hatay and it has only deployed a small group of people to provide assistance upon the request of Turkish officials.

Recommendations for Ankara

To date, Ankara has largely ignored calls from international and national refugee organizations and rights groups. Most recently in June, Amnesty International listed a number of issues and asked Turkey to ensure the safety of Syrian refugees and access for national and international monitors. The advocacy group emphasized a number of concerns including the close proximity of the camps to Syrian border, registration and screening procedures, and the temporary protection policy. Other concerns raised by different humanitarian and human rights groups include complicated asylum procedures, lack of qualified refugee lawyers, and restricted access of NGOs and the media to the camps.

Overall, three recommendations are commonly voiced by refugee organizations regarding the Syrian refugees in Turkey:

First, the close proximity of the camps to the Syrian border poses a serious security threat to the residents. Currently, Syrian refugees cannot live outside the camps by their own means and relocation to a city other than Hatay (which borders Syria) is not option. In April 2012, several Syrians were reportedly injured after stray bullets from clashes in Syria hit the camp in the Kilis province. Therefore, Ankara needs to ensure that all refugee camps are at a safe distance from the border areas, where the Syrian military occasionally carries out operations against the Free Syrian Army.

Second, despite calls from numerous refugee advocacy groups and international and national NGOs, Ankara has barred regular access to the camps. Turkey needs to grant refugee and human rights NGOs, particularly specialist organizations with expertise in emergencies, regular access to contact the residents and monitor practices in the camps. This will improve transparency and accountability, and ensure and strengthen Turkey’s adherence to national and international standards. There have been reports claiming that Turkey’s camps are being used as training bases and operational centers for cross-border attacks inside Syria. Ensuring media access to the camps may help check the validity of such stories and allegations.

Lastly, from the onset of the crisis, Ankara has taken on the management of refugee operations by itself and has tasked the AFAD and TRC to run the refugee camps. Yet, the AFAD was founded only a few years ago and has never dealt with an emergency concerning refugees before. The agency’s poorly drafted English public statements can be an important indicator of its readiness and competency level. Considering the difficulties experienced both by the AFAD and TRC during last year’s Van earthquake, entrusting the operations exclusively to these agencies is risky in a volatile area.

Furthermore, the tent cities, which are currently hosting tens of thousands of Syrians, proved ineffective and pose life-threatening risks in winter conditions. Last year, eleven people died in the eastern Turkish province of Van in tent cities set up and administered by the AFAD. Last month, two Syrian children died after fire broke out in the Yayladağı refugee camp. In another incident, several refugees and Turkish police officers were injured after a riot broke out at a refugee camp in the province of Kilis, reportedly over lack of water. Involving specialist international organizations may help Turkey ensure that the basic needs and safety of Syrian refugees are addressed in the long term.

Considering Turkey’s position on Syrian refugees, Ankara seems to perceive the crisis in Syria as a short-term emergency. Turkey may be counting on the creation of a UN Security Council-authorized buffer zone inside Syria that would provide a safe haven for fleeing Syrians. However, if Russia’s position in the crisis is any indication, such a decision from the UN Security Council does not seem plausible, at least for the time being.

With the humanitarian situation inside Syria getting worse, the number refugees entering Turkey may soon exceed Turkey’s capacity to respond. The crisis may well extend into the winter months and Ankara needs to make sure that it has a long-term contingency plan – a plan that involves cooperation with international organizations and specialist NGOs. Without proper safeguards and transparency, the status of thousands of Syrian refugees in Turkey remains entirely at Ankara’s political discretion which comes with serious risks. Therefore, Turkey should match its talk of democracy and transparency in the Middle Eastwith policies that are of a nature expected from a democracy.

The views expressed in this article are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment