"In Poland it took ten years, in Hungary ten months, in East Germany ten weeks: perhaps in Czechoslovakia it will take ten days!"

So noted the Czech poet and politician Vaclav Havel, in his prescient and now famous comments to the British journalist Timothy Garton-Ash on the revolutions of 1989. In Egypt, it took just eight days. Not the revolution, whose denouement lies beyond a thick fog and may never emerge, but the shattering of Hosni Mubarak's aura of invincibility. Regardless of whether – or how and when – the regime crumbles – for its central figures remain in government under the military veneer – it is these crucial early blows that have left it riven with fractures and devoid of its psychological grip on Egyptian subjects. By virtue of these small victories, the uprising constitutes what is already the most far-reaching internal convulsion in an Arab state since their expulsion of colonial powers midway through the last century.

Though the script is unfinished, the remnants of Mubarak's regime cannot survive the cocktail of mass demonstration, fresh American pressure, and military ambivalence. And when they tumble, though the change will by itself be superficial, the ground will shake. Egypt, the most populous country in the Middle East, is the cradle of the Arab world. It was the epicentre of pan-Arabism, the political philosophy that sought the unification of the Arab world, even briefly merging with Syria between 1958 and 1961 to form the United Arab Republic. It stood at the forefront of four historic wars with Israel, including the 1973 Yom Kippur War in which a brilliant surprise attack across the Suez Canal destroyed the assumption of Israel's military dominance that had taken hold after 1967. Years earlier, it had faced a coordinated Anglo-French-Israeli invasion which was diplomatically repelled by Washington and Moscow, burnishing Egypt's reputation as a standard-bearer for non-alignment. Egypt is more than just another Arab nation; it veers towards the civilizational, and therefore holds out the distant hope of serving as that democratic beacon which the US could not implant in Iraq.

If Tunisia was the catalyst, Egypt will be the turbocharger, auguring change where none was thought feasible. The fate of Amman, Damascus and Sana'a will be shaped on the streets of Cairo, just as Poland’s tremors of the 1980s rippled violently outwards. It is impossible to exaggerate the long-term significance of these currents. In Albert Hourani's landmark 'History of the Arab Peoples', the word 'democracy' does not appear in the index even once. Today, the so-called 'Arab exception' lies discredited, not because democracies are mushrooming – Tunisia's 'transition' thus far hardly deserves the name – but because a cascade of expectations is already underway.

There are good reasons to be sceptical of the snowballing theory of revolution. Behind the iron curtain, knock-on effects were direct. When Hungary opened its borders in May 1989, for example, the sheer physical possibilities for East Germans transformed at a stroke. And the Soviet decision to forego intervention was as important as internal uprising in fomenting change. In the Arab world, neither borders nor external powers are central to the narrative. Egyptians are not clamoring to escape their country, and the source of repression is basically indigenous.

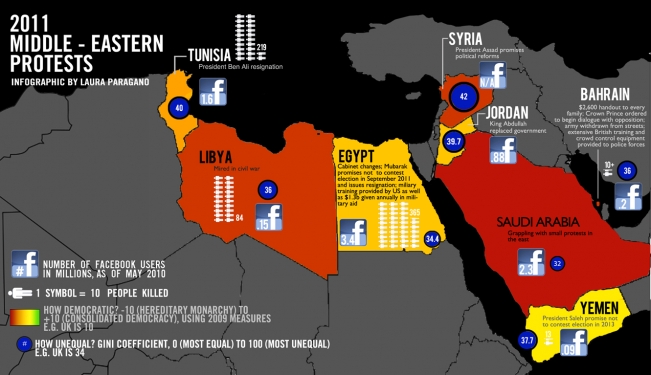

The talk of contagion might also be a touch simplistic. There are as many varieties of Middle Eastern tyranny as there are despots. In Syria, despite the superficial similarities to Mubarak, Bashar al-Assad is seen by many as an earnest reformist blocked by an ossified ancien regime. Inequality is less severe and, unlike in Tunisia, the army is deeply woven into the fabric of the government through sectarian and other ties. Before assuming office, Assad pushed modernizing schemes, including expansion of internet access, and led popular anti-corruption projects. Early in his tenure, hundreds of political prisoners were freed and a few openings for the media and intellectuals, some later reversed, took place. Syria's anti-Israeli foreign policy also sits more comfortably with its population than the frosty peace upheld by the regimes in Jordan and Israel, allowing the government to avoid the scorn directed at Egyptian regimes since the 1978 Camp David Accords. There are mitigating factors elsewhere too. In Saudi Arabia, oil wealth and American backing allows the regime to ignore representation by foregoing taxation. A large and disenfranchised migrant worker population bears the burden of menial labour (but even there, half a million unemployed and heavy internet censorship fuel discontent). In Jordan, years of modest reforms have furnished the regime with a safety valve. The Islamists there largely targeted their ire at the government, not King Abdullah himself.

But across the Middle East, the region's wretched tyrants are panicking – sacking cabinets, pleading with parliaments and reinstating food subsidies. Expert opinion was wrong-footed in cautioning against a repeat of Tunisia. Even President Saleh of Yemen, who has ruled for over three decades and enjoyed over a year of massive American support for his security services in the aftermath of the so-called 'Underpants Bomber', announced that he would step down at the end of his term. This is because objective conditions – a pseudo-Marxist concept of limited use – supply only part of the story. Revolution is not merely a function of youth bulges and class divisions and unemployment but, above all, the evaporation of layers of fear encrusted over decades. Like an atom splitting, the resultant energy far exceeds that suggested by social and economic circumstances alone. And like a chain reaction, the infliction of indiscriminate violence by reeling regimes simply sweeps wind into the sails of burgeoning demonstrations. Whether the result was passive cowering, as with Bahrain's royal family, or civil war, as in Libya, the aftershocks of Tunisia were impossible to avoid.

As the fruit-vendor Mohamed Bouazizi set himself in ablaze in Tunisia last month, he also set alight the mind-forged manacles of Arab (and, of course, Iranian) subjects, only singeing some but melting others. Arab identity has been galvanized over the past decade, in part by the introduction of new forms of communication. One widely-cited study by American scholars has demonstrated that 'the more days a week that participants said they viewed Al Jazeera or Al Arabiya, the more likely they were to claim “Muslim” as their main political identity, rather than their national identity' (Nisbet and Myers). In particular countries, states have actively pushed their citizens to identify as Arabs. This lubricates the cross-boder flow of subversive ideas. The effects of these older media were in some ways more significant than the exaggerated digital samizdat of Twitter and Facebook. All this partly explains why Bouazizi's propaganda of the deed, an act mimicked as far afield as South Asia, was so successful. Autocrats see their regimes sinking into the sand amidst a transnational audience, hence their waves of rearguard action. But as in 1989, partial concessions issued so rapidly will simply pique a taste for more. That taste will be contained, but it cannot be extinguished.

It is also worth noting that despite Tunisia's optimization for revolution – it is a small state, with high levels of education and a sizable middle class – it is not unique. Tunisia was primed, but the wider region is not moving from a cold start. The American political scientist Samuel Huntington wrote in his seminal book 'The Third Wave: democratization in the late twentieth century' that:

'Middle Eastern economies and societies were approaching the point where they would be too wealthy and too complex for their various traditional, military, and one-party systems of authoritarian rule'.

Writing twenty years ago, Huntington argued that Egypt was rapidly heading towards 'the transition zone' of $1,000 to $3,000. Egypt's per capita income today is roughly $2,700 according to estimates by the IMF and World Bank. In the 1991 dollars used by Huntington, that is approximately $1,700. Even more remarkable is that in terms of Purchasing Power Parity (PPP), Egypt would be considered to have shot straight through the transition zone altogether.

In other words, the growth spurt overseen by Mubarak pulled the regime into precisely the most perilous terrain for dictators anywhere. These calculations are guided by so-called 'modernization theory', which is hotly disputed amongst political scientists, many of whom favor other arguments for explaining why states democratize. It is worth recalling that the per capita incomes of the world's oldest and largest modern democracies, the United States and India respectively, were below any plausible transition zone when their democratization commenced. But this is a useful tool to understand the socio-economic context of an unprecedented mobilization of citizens.

The opportunity for citizens to seize democratic space in the newly enlarged public sphere will occur at a different pace in different parts of the region. In Jordan and Saudi Arabia, the vast and well-oiled security apparatuses will be deft at blocking mass protest, and early concessions are most likely to have bought time. In Syria, Assad will use his reviled party as a lightning rod for dissent. But in Libya and Bahrain, and soon Yemen and Algeria and Sudan, the cues from Cairo spell resistance of the sort that no Arab of this generation can even envision, even though the outer works of all these regimes will remain firmly in place for years to come. The Kefaya protest movement of 2004-2005 in Egypt was a seminal grassroots coalition against Mubarak and the succession of his son, Gamal. It was a historic but ill-fated effort that could not transcend the blanket of fear. It faded into the faux-democratic morass of fixed elections and targeted repression at which Mubarak was so well practiced. Now that blanket has been hurled away by a good portion of Egyptians, many of whom would have been expressing their true opinions in public for the first time on 25 January, the first day of protests.

What is most important is that once proud parties of transformation, like the Ba'ath in Syria, have shrunken into cynical vehicles of patronage politics and self-perpetuation. Once self-described revolutionary governments have morphed into parodies of their postcolonial selves, their leaders festooned with decorations celebrating fictional military victories that serve only to obscure fictional political triumphs. They therefore have no ideological shield to parry their rebels' blows, no counter-revolutionary verve with which to muffle the newfound voices. According to defecting Libyan military officers, Muammar Gaddafi had declared that he was the one who created Libya, and that he would be the one to destroy it. What could more perfectly encapsulate the nihilistic, self-serving essence of the autocratic creed? As mighty rulers like Mubarak, Saleh, Ben Ali and Gaddafi cower after a combined 118 years of rule between them, the age of easy security is gone forever, and it will not come back. Shakespeare's Richard II lamented the 'mortal temples of a king'. It is hard not to imagine Mubarak in Sharm el-Sheikh, like Richard, sitting upon the ground and telling sad stories of the death of kings.

Authoritarianism will not depart the region. Indeed, it may yet preserve its grip on Egypt, where the military is growing violently impatient of the residual presence in Tahrir Square. But it will be over-the-shoulder rule under a trembling democratic ground. In Russia, where the country dissolved its Communist Party with remarkably little tumult, dissent was never expressed in concentrated spasms of the sort seen on the streets of Cairo, Tunis and Benghazi. That meant that the Putin regime could regress to a form of soft authoritarianism without fear of popular resistance. The state's often ruthless grip over information has helped in that regard. In Cairo, the Mubarak regime tried to arrest and attack journalists, but could not stem the overwhelming tide of imagery and testimony that flooded out to the outside world and washed around Egypt, giving succor to those squaring up to the state. In other words, the process of resistance will inculcate in its practitioners a democratic habit. Regimes, cognizant of the fault-lines running through their structures of power and patronage, will interact with their societies on fundamentally changed terms.

In all this, the United States is the principal interloper. President Obama insisted that the precise date of Mubarak's departure was 'not a decision ultimately the United States makes or any country outside of Egypt makes'. In purely formal terms, he was correct. Either the regime would unilaterally concede its dominance, or it would be compelled to do so by the suasion of crowds, rebelling officers or hitherto loyal allies. The annual average flow of over $1.3bn to the powerful Egyptian military and the threat to its continuance was a sort of suasion although the Pentagon lobbied hard behind the scenes to continue the flow regardless of what the regime did in Cairo.

What is clear is that the interests of the United States are misaligned with the hungry impatience of protesters. The administration requires time to ensure that its interests – from Egypt's support for the blockade against Hamas to the Egyptian intelligence apparatus' operations against terrorist groups – are locked into any new structures of power that emerge, and that its regional allies insulate themselves from the ramifications of a changing order.

The opposition requires precisely the opposite: that a new government is tabula rasa, untainted either by unpopular policies towards the Palestinians or burdened with the institutional residue of a police state. In this, let there be no doubt that they will be disappointed. The current regime will not fade quietly into a good night, but instead has sought to ensure that the months until the elections are spent salvaging as many of its own privileges as possible, from military officials in key posts and stringent limits on presidential candidacy to funneling resources to consolidate areas of support. The surviving elements of Mubarak’s party and a coterie of power-brokers will employ the state's intelligence and security networks to disrupt the opposition, contain mass protest, and secure army and business backing for this supposedly orderly transition.

Orderly, yes, Radical, no…

Egypt is likely to evolve into what the Harvard political scientists Steven Levitsky and Lucan Way have termed 'competitive authoritarianism'. The military, whose loyalty to the regime as a whole has been greatly underestimated throughout the crisis, will underpin the new order, probably emerging with more influence than at any time since the 1980s. Its masterstroke was declaring loudly that it would not fire on protesters. In doing so, it bolstered its already solid reputation as a truly national institution of impeccable professionalism and legitimacy, but also hemmed in the regime and forced the politicians to actively seek its loyalty through power-sharing. The military's leaders are also determined to protect its extensive network of economic interests and societal privileges. It is well known that junior officers in Eypt, in common with those in other paranoid authoritarian states, are not only historically quiescent (the coup in 1952 notwithstanding) but also ruthlessly stripped of power if their initiative grows too great. And although a recent Wikileaks cable revealed that 'one can hear mid-level officers at Ministry of Defense clubs around Cairo openly expressing disdain for the defense minister, Field Marshall Tantawi, these grievances are muffled by an organizational structure that stovepipes command and control, thereby preventing junior ranks from coordinating opposition. The closest parallel for Egypt may be Pakistan's praetorian military establishment; although in Pakistan there is a far sharper distinction between the army and civilian political parties. It is true that the senior echelons of the military have no wish to sully their reputation by anything as base as day-to-day government, but this does not preclude a subtle, pernicious veto over core policies – such as foreign policy, and the military's economic empire – being imposed on a future elected government.

In other words, a perverse commonality of interests exists between the Obama and Mubarak governments in favor of prolonging a transition and maintaining elite counterweights against populist groups, whether Islamist or otherwise anti-American. This explains the apparent paralysis of the administration throughout the crest of the agitation in the early days of February, and it is this convergence that will ensure a slow and frustrating period of reform over the next months. US policy has been reactive, conservative and dogmatic. Though Obama eulogized the crowds in Tahrir Square in proportion with their growing size, he did not extend the praise to the more modest thousands in Yemen or Algeria, Jordan or Saudi Arabia. Towards them, he no doubt felt personal sympathy but professional fear. The lessons for the region's democratic aspirants are simple: size is everything; preserve momentum; harness the West's political language to mobilize its capitals; and, finally, do not assume that the United States will fight your battles.

Lastly, what will be the region's trajectory? No one who has tracked the Iran of 1979 or the Lebanon of 2005 would romanticize revolution, nor suppose that when the dominos lay piled on the ground, pillars of enlightenment will stand in their place. Egypt is certainly vulnerable to stalling on the road of reform, and not only for the reasons mentioned above. It has emasculated its parliament, empowered its military to penetrate into the far corners of a sclerotic economy, and fallen into a precarious dependence on moderate food prices and strong energy exports. But equally, its public sphere is not unpopulated – it is a great deal more like the Poland than the East Germany of 1989. A private sector media industry has expanded the space for dissent, and the Muslim Brotherhood has participated in electoral politics for many years, albeit with various shackles imposed by the regime. These advantages will ease Egypt's democratization, if indeed that is what follows after September's elections. But they do not completely guarantee that an Arab spring will not resemble either its ill-fated Czech counterpart, whose reforms were crushed under Soviet tanks within the year, or the sad course of Central Asia, whose post-Cold War hopes lie crushed under a slew of strongmen from Belarus to Tajikistan.

What is clear that with or without the flows of American aid, and regardless of the role played by the Muslim Brotherhood in the tumult, the specter of latent Islamism is a hollow threat, which can no longer stifle the yearning for self-determination for which hundreds of Egyptians have already paid with their lives. Not only were the Muslim Brotherhood a marginal presence in the early days of protest, but their party is a coalition of necessity that would fracture and fall apart under genuinely free elections, leaving a rump of extremists and a much larger group of Turkish-style pragmatic moderates willing to cut deals and make compromises.

The great Arab scholar Ibn Khaldun wrote in his 14th century 'Muqaddimah', translated as 'Introduction to Universal History', that 'Egyptians are dominated by joyfulness, levity, and disregard for the future'. But it is precisely to salvage a future slipping away from them that the Egyptian people stood up after Tunisia. They did so with occasional levity, as the fraternal crowds in Tahrir Square indicated, but equally with a singularity of purpose and intense solemnity. They were not dominoes, not passive instruments of a history grinding to its end, but, like democratic people anywhere, citizens seizing their citizenship. This democratic quest will take longer than the eight days of Mubarak's first capitulation but the genie has been unleashed from the bottle and there is no way it can be put back. For the first time in its post-independence history, one part of the Arab world will begin to chart its own course; not one set in someone else's corridors of power.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment