This was the month of January in 2006. I, with my team members, had gone to Strait Island, where some Great Andamanese people were staying distributed in eight households. There were more children than adults and it seemed no one had any work to do, as food supply was given to the community as a subsidy. The men used to spend time either fishing at the jetty or roaming in the jungle, which was neither very dense nor very large. Women sat under a tree, gossiping, and children either played cricket with a make-belief bat or just surrounded the chatting women. The whole atmosphere was very relaxed and time seemed to pass very slowly. Despite the small adult population, the ones who were in Strait were those who had some competency in their heritage language that kindled hope of finding some folk tales. I had found out that out of all the adult folks, only Nao Jr claimed to remember one story. Only one! Well, I decided something is better than nothing. Thus, I approached his hut with expectations and hope.

Nao Jr was seemingly always busy, either ‘on duty’ in the only medical unit that Strait Island had, distributing medicines in case there was a need for anyone on the island, or fishing in the early morning or late evening, or just sleeping, which was his favourite pass-time. He agreed to help me record the folk tale only after 9 at night and I agreed to his terms, as I was excited to find at least one person in the entire habitat of eight households who claimed to remember a tale. He promised to visit me in the guesthouse. I was very anxious to receive him at the stipulated time.

I remember distinctly that it was 21 January 2006. Nao came to the guesthouse, thinking that he would finish the job in one evening. Little did he know that linguists have the bad habit of checking each and every word and phrase that is uttered. In the first sitting, he tried to narrate the story in Andamanese Hindi. He would halt in between, groping for the right words or phrases. When he was not satisfied with the Hindi version, he would suddenly revert to the appropriate Andamanese word. This was rather exciting and educational for me. The long-lost language was getting revived gradually in an ancient tale. I never expected this!

The loud choruses of the crickets and frogs had begun in the tsunami-created marshes and swamps behind our guesthouse; the power had been switched off and we were all sitting in the dark. We knew it was past 11 pm. We used to get electricity only for two hours. Nao wanted to retire. I extracted a promise from him to visit us the next day, at his convenience, but with the Andamanese version and not the Hindi one. He said he had forgotten it all. When I insisted that he could attempt to remember it at night while going to bed, he agreed to try but was sure that his memory would fail him. ‘Chaaliis saal se sunaa nahiin, kaun bolega? (It has been 40 years since I have heard it; who can narrate it?)’ He was sure he would disappoint me.

Then came the next day. I was making some grammar notes sitting on the wooden bed in the afternoon. I saw Nao standing at my door with an expectant look on his face. The moment I looked up, he said in Hindi, ‘Kuch kuch yaad aataa hai (I can remember a little).’ I invited him in and then we sat around the bed, turning it into a makeshift table. He started narrating the same story in short Great Andamanese phrases, not very fluently, but mixed with Hindi. Narayan, my student, assisted me in recording and transcribing the story. This is how our long journey of the Great Andamanese narration started, a journey into the past. I would interrupt him to get Hindi equivalents and he could, with a 90 percent success rate, render them. It took us several days, to get the full version of the narration of ‘Phertajido’ and the subsequent word-for-word translation. Sometimes, we would have our sessions in the afternoon and sometimes after 9 pm, as he was always busy fishing by the Strait Island jetty after sunset. This was a great story and I could see he loved narrating it.

The translated version of this story had some gaps, which I realized only after coming back to Delhi. I decided to go through the entire process again during the next trip. I was lucky enough as Nao obliged me during my next trip to Port Blair in December 2006, almost 11 months after our previous visit.

On reaching Port Blair in December 2006, I discovered that Nao was in Strait Island and not in Port Blair as I was informed by a tribal friend on the phone before I left Delhi. The AAJVS officials not only failed to honour my already sanctioned permit to visit Strait Island but were also on the lookout to catch and arrest me if I pursued my research. No one in the mainland would believe that a researcher could be arrested for hearing a story from the Great Andamanese tribes for work. Under the pretext of safeguarding the protected tribes, the concerned official would disregard the sanction given to us by the Home Ministry and would expect us to grease his palms. I neither had the means nor the inclinations to oblige him.

There was no way of informing Nao of my arrival in Port Blair. Unfortunately, Strait Island had no phone connections. The only wireless communication that the island had, was in the hands of the government officials. I had no option but to visit the Port Blair jetty and take a chance and see if I could run into any of my tribal friends on the ship. Ships for Strait Island leave very early in the morning at about 5:45 am. It was 19 December 2006; I reached the jetty much before the stipulated time. A crew member from one of the ships recognized me. By then, many local officials, especially those who worked on ships and boats, had started recognizing me as a friend of the Great Andamanese tribes. As soon as this man, a ticket checker at the departure gate saw me, he indicated towards the next ship moored in the distance and said, ‘Go and see Reya. She is going to Strait Island.’ This was a girl from the Great Andamanese tribe, whom I knew very well and who had married a Bengali man. I ran towards her, lest I lose her. She immediately recognized me and greeted me with a namaste. She introduced me to her husband. She asked me in Hindi, ‘Kab aayaa (when did you come)?’ Reya is one of those Great Andamanese tribal girls, who loves to amalgamate herself into our society and is happy to forget her heritage language. I told her that I desperately wanted to see Nili (the pet name of Nao). She informed me that Nao was on Strait Island and had no plans of visiting Port Blair. My world was falling to pieces.

I knew requesting the administration to transport Nao Jr to Port Blair would not help. I knew that getting permission to travel to Strait Island will be equally difficult, as some officers-in-charge were against any research on these tribes. It is a shame that the members of these tribes are kept as captives in their own land and are restricted from meeting other Indian citizens. Had it not been for the initiative of the Great Andamanese themselves, they would have never befriended locals and visitors like us. I immediately fished out a piece of paper from my purse, wrote a note in Hindi in bold letters, and gave it to Reya to pass it on to Nao. I told her to ask him to have it read out to him by one of the school-going children. I also told her that the sole purpose of my trip to the Andamans was to meet Nao and my other tribal friends, but Nao in particular. She promised to deliver the message.

[Listen to a song included in the book: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zuqMVBnNoWs.]

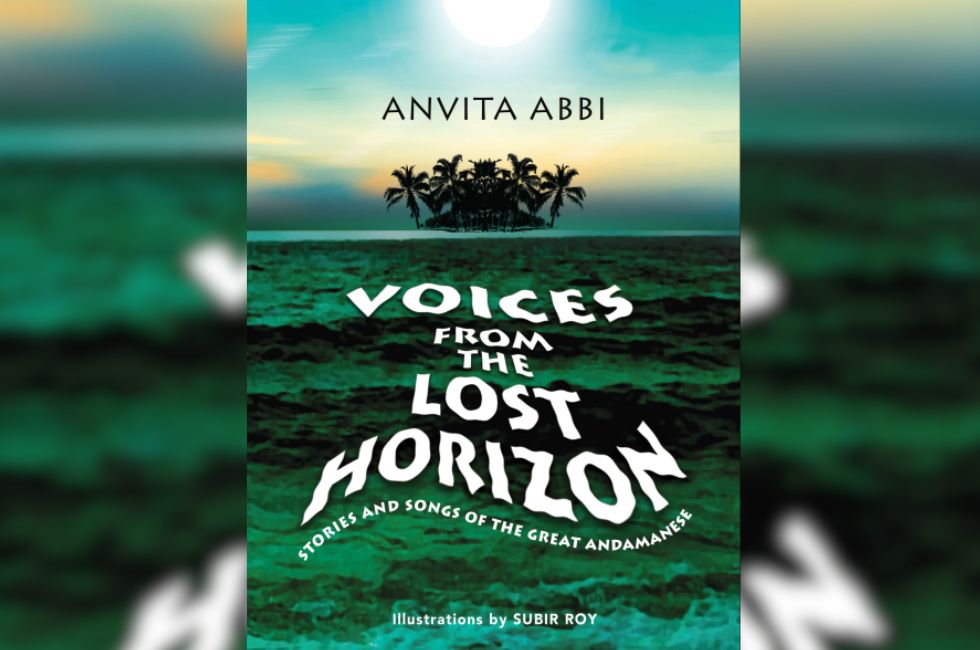

[Niyogi Books has given Fair Observer permission to publish this excerpt from Voices from the Lost Horizon: Stories and Songs of the Great Andamanese, Anvita Abbi, Niyogi Books, 2021.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment