Following the capture of Goa on India’s western coast in 1510, the Portuguese soon established trading posts in other parts of the country. In the prosperous province of Bengal towards the northeast, factories were set up in Chittagong and nearby Satgaon, the then mercantile capital of the province. The factories developed into fortified settlements, from where Portuguese merchants engaged in a very profitable trade, both in necessities like cotton, sugar and saltpetre, as well as in luxury items.

For nearly a hundred years, from around the 1550s until the 1640s, silk embroideries from Satgaon, which the Portuguese commissioned for their homes in India and for the European market, were among the most coveted luxury goods. The Satgaon embroideries for clients in Europe were shipped to Lisbon, which city held a preeminent position in Europe in the trade of Asian luxury goods.

We do not know the designs on the early embroideries which the Portuguese ordered in Satgaon, but the iconography of most preserved examples, which are believed to date from the end of the 16th century onwards, is basically European. Drawings after European prints probably served as examples. Quite a number of the embroidered motifs are based on biblical stories and on classical mythology. They also include disparate images of mermaids, month-by-month rural activities in rural Europe, hunting scenes with European figures and marine scenes with European vessels. The double-headed eagle (symbol of the Habsburg dynasty) and the self-sacrificing pelican (symbol of the Eucharist and Christ), are also depicted, often rather prominently. Next to these European images, we find motifs derived from Hindu mythology, particularly from the Vaishnava legend of the Great Flood, as well as mounted elephants and tigers. The same images on several Satgaon embroideries indicate that drawn examples or stencils based on them were used repeatedly.

Almost all the embroideries are executed in pale yellow tussar silk, laid on two layers of white, plain-weave cotton fabric, with a layer of cotton wool occasionally sandwiched in-between. The motifs are embroidered in chain stitch, arranged in rows. French knots, a type of stitch where the thread is knotted around itself, are used in narrow borders and as fillings of non-figurative images. In a number of the embroideries, the space between the images is covered by tiny back stitches. The thread used, consisting of a number of S-twisted yarns, is rather thick.

The majority of embroideries made for European clients which are preserved in their complete form are colchas, the Portuguese word for coverlets (Fig. 2.1). Some colchas were kept in so-called Kunstkammern (‘Chambers of Art and Rarities’, also called ‘Cabinets of Curiosity’ and ‘Chambers of Art and Wonders’), which collectors installed in their houses, castles or palaces. When used, these embroideries served as canopies, wall hangings, bedspreads and floor coverings.

Capes made from Satgaon embroidery are preserved in much smaller numbers than colchas. They are generally pieced together from embroidered panels which are sewn together. However, a few examples made from a single length of embroidered fabric have also been preserved. The shape of these capes is based on the capes worn at the Spanish court. Although the ‘Satgaon capes’ look like copes, the iconography on the preserved examples is not specifically Christian, and there are no sources which indicate that they were used as ecclesiastical vestments.

Satgaon embroideries for European clients were shipped to Lisbon, which city held a preeminent position in Europe in the trade of Asian luxury goods. We know that as early as 1558, the Portuguese Queen Catharina of Austria (1507–1578), an avid collector of curiosities, received three Bengal colchas. These are probably lost.

Indeed, relatively few Satgaon embroideries survive, but thanks to their mention in inventories of the Spanish and Austrian Habsburgs, the Kunstkammer in Prague of Emperor Rudolf II and in the inventories of the Medici in Florence and royal and noble families in Spain and Portugal, we know that they were present in a number of palaces and wealthy homes in Europe. The extended Habsburg family in particular used these precious embroideries as gifts. In London, Satgaon embroideries were already being auctioned in 1618 and 1619.

A colcha and a cape are preserved in the Kunstkammer in Schloss Ambras in Innsbruck, which Ferdinand II, Archduke of Austria (1529– 1595) created in this castle. Both are mentioned in the 1596 inventory of the Ambras Kunstkammer. No other Satgaon embroideries have such a well-documented provenance.

In 1632, the Mughal army expelled the Portuguese from Satgaon. A number of Portuguese stayed on, however, and the production of embroideries for the European market probably continued for some time. Nothing is known about orders for Satgaon embroideries by employees of the Dutch and English East India companies who were engaged in the private trade of luxury goods. Both companies established various trading posts in Bengal in the 1630s, from which posts, however, hardly any Bengali luxury goods were shipped to Europe. Presumably, the embroideries no longer appealed to discriminating, fashion-conscious clients in northern Europe after the 1640s, as their representations, which were largely based on Renaissance imagery, had become obsolete.

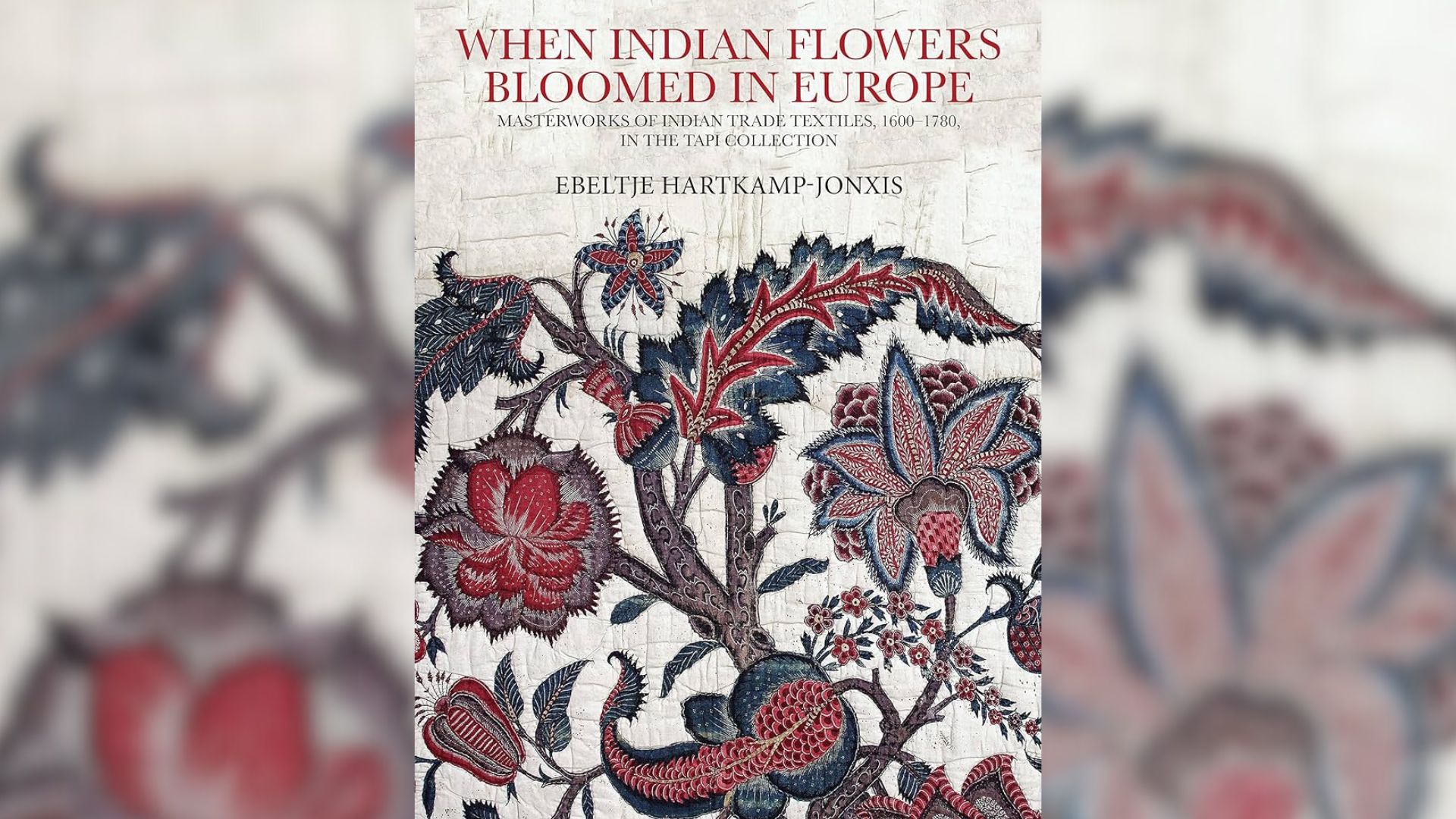

[Niyogi Books has given Fair Observer permission to publish this excerpt from When Indian Flowers Bloomed in Europe: Masterworks of Indian Trade Textiles, 1600–1780, in the TAPI Collection, Ebeltje Hartkamp Jonxis, Niyogi Books, 2022.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment