A fleeting but magnificent era of artistic history is the mid-century modern movement. It was an interlude of geometric simplicity and craftsmanship in the space between the stylishness of Art Deco of the 1920s-30s and the Jetsons-like space age vogue of the 1960s. It was the art of the era of aircraft.

Mid-century modern design is best known for furniture, among the best ever produced (like the curved writing desk, with a lip, at which I sit right now). Mid-century furniture flourished at the simultaneous peaks of aesthetic science, ergonometric design and new high-precision woodworking technology. Sadly, its slow death ensued with the plummet of profit margins and consumer discrimination. Designers like Charles and Ray Eames lost out to mass-produced furniture by Ikea and others.

Alongside furniture, however, mid-century aesthetics gave us amazing architecture and art—often both in one place. Every week I visit a stunning example, Our Lady of the Pillar Catholic Church in Half Moon Bay, California, affectionately known as OLP.

An unrecognized jewel

OLP is a mostly unknown, seaside country church with an intricate, curved interior of stained glass murals under a soaring aircraft-hanger roof. The choir at 10:00 AM Mass has only three people, of whom my wife Criscillia and I are two. I may be the only person there who recognizes OLP’s unique artistic heritage, which is why I want to keep it as it is, and why I’m writing this.

Since OLP is unknown, let’s compare it with an actually famous mid-century building, First United Methodist Church of San Diego. Here’s what that church looks like inside:

Note the curved barrel ceiling and angled supports, which bisect horizontal beams. The ends of the pews echo that parabolic art, as do the outlines of the chandeliers, shaped like rocket ships. In great buildings like this, as with those by architect Frank Lloyd Wright, motifs reappear across the floor, the furniture, the windows and the roof. Everything elegantly fits.

Now let’s look at OLP. From the outside, it looks simple and boxy, a cross between a mission church and a high school gym (although the gardens are magnificent).

The inside of the church is a complete contrast. Curves dominate, a likely relation to the new age of aviation in the 1950s, when the church was built. At that time, San Francisco had just opened its international airport “over the hill”—this little town of Half Moon Bay, although just thirty kilometers south of San Francisco, was effectively isolated from San Francisco and the rest of the Bay Area by steep mountains. Half Moon Bay had gotten its own airport only a few years earlier, thanks to the Army and World War II.

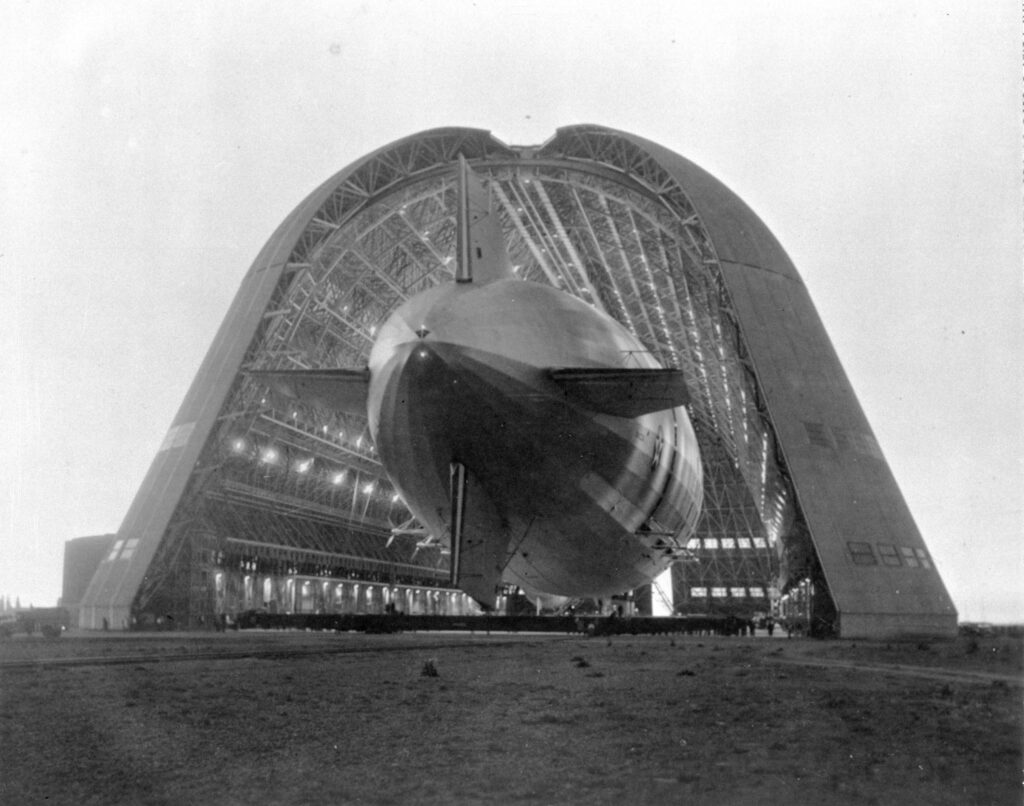

Also south of San Francisco, but on the populated side of the mountains, was one of the largest buildings in the world, Hanger A at Moffett Field. The hanger was built in the 1930s to accommodate Zeppelins.

The angled sides and curved roof of this giant hanger resemble a smoothed-off trapezoid.

Now let’s look inside OLP:

There are actually three kinds of curved arch here: the most boxy is the wall/ceiling shape, then the wider arch, then the narrower arch whose perfect half-circle centers on the circle of the Virgin Mary’s halo. That narrower arch has the same shape as the one in San Diego, as do the vertical struts bisecting horizontal beams.

The same curves appear looking from the altar towards the entrance. From this angle, the circular Rose Window is prominent. It carried over from the older church which this one replaced.

The chandeliers contain gentle arcs at their tops, echoing the arc motif seen in the roofline and the stained-glass windows. Unusually, the curved flares of the cylinders imitate aircraft-engine cowlings, a separate invocation of aviation in addition to the aircraft-hanger shape.

So it looks to my amateur eye as if this tiny rural church contains several of the key motifs of the famous San Diego church, in particular the angled support columns, aircraft-hanger roofline and matching aircraft/rocket chandeliers. But here’s the catch: OLP held its first mass in 1954, a full ten years before the San Diego church was built. The little rural church beat out the big famous one and perhaps even inspired it.

But what makes OLP so spectacular is the cycle of stained glass windows portraying eight frames of the Christian narrative. The windows incorporate circular arcs in the cartoonish, abstract mid-century style, a style that rarely depicts human figures.

1. The Annunciation. The arcs here intersect above Mary, as if forming the roof-beam of a church.

2. The Nativity of Jesus. Here the arcs intersect above as the beams of the manger, and below to cradle the baby.

3. The Three Wise Men bringing gifts. Here the arcs intersect to form the Star of Bethlehem

4. Jesus enthroned as Christ the King. The arcs form his crown:

5. Pentecost, in which the Holy Spirit descends on the Apostles.

6. The entry of Jesus into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday. The arcs here are palm leaves.

7. The Crucifixion. The arcs are asymmetrical, like a spiral.

8. The Angel of the Resurrection. The arcs form a sun:

Below, at eye-level with the congregation, is a very different view. There is a large stained-glass “mural” that depicts the Christian history of California and its missions. The same arc-shapes that appear in the upper windows reappear as dividing shapes throughout the mural, but in muted blues and golds which match the original rose window. Note also the metal decoration wrapping the angled vertical beam, part of the metallic aviation theme.

My photographs do not do this church justice, and my dilettante’s knowledge of art and architecture should not be the last word on this gem box of a church. I sincerely hope that others more qualified will visit this beautiful place, to know what it is to sit, sing or worship inside a unified work of art.

OLP is a church, not a museum

But what if no one knows it’s art?

The photos above show the building, not the people. Lots of old people, yet enough newborns to coo together during service. Three different languages: English, Spanish and Portuguese. Rich and poor. And brought together recently through tragedy, when three church members were killed in a violent attack.

The congregation works hard on the church. A few years ago, when Covid first hit, construction-minded men jerry-rigged a giant tent in the parking lot so Mass could be held outdoors. It was held there for two years. The services were the only continuous services in the area. OLP people also share a love of neat, bright decoration. The gardens are pretty and thriving, the festive fabrics stunning, the flowers always vibrant.

And therein lies the problem. Those abstract modern chandeliers don’t have the bright and festive look most OLP folks like, and they’re the ones who worship there. Over the last few years, congregants have renovated almost every element: the church now has a freshly painted ceiling, a new carpet, a new altar, new pews, restored paintings. Those rusty, abstract chandeliers are now the dullest elements in the building.

Some parishioners want to replace those old chandeliers with these brand-new ones:

These sparky new things don’t match the old aesthetic, but many parishioners like them. It’s possible that OLP, a perfect example of a bygone form of art, like other art before it, will slowly erode its coherence to serve the people who use it now. It’s not just their right, it’s their obligation to worship as they want. The church belongs to them, not to history. But oh, what a wonderful history it is.

[Throvnica Chandrasekar and Anton Schauble edited this piece.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment