When Discovery Channel released its 45-minute documentary on NEOM titled The Line, the associated marketing urged viewers to “embark on a remarkable journey into the unprecedented urban living experience” taking shape in Saudi Arabia. According to the documentary, NEOM, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s ambitious urban development project, is “the Babylon of the 21st century in the making.”

The film features a bevy of architects, including Peter Cook, who eloquently and at length expatiate on just how extraordinary and visionary bin Salman’s city of the future is. It prominently features the crown prince himself interjecting pithy insights such as, “Since we have an empty place, and we want to have a place for 10 million people, then let’s think from scratch.”

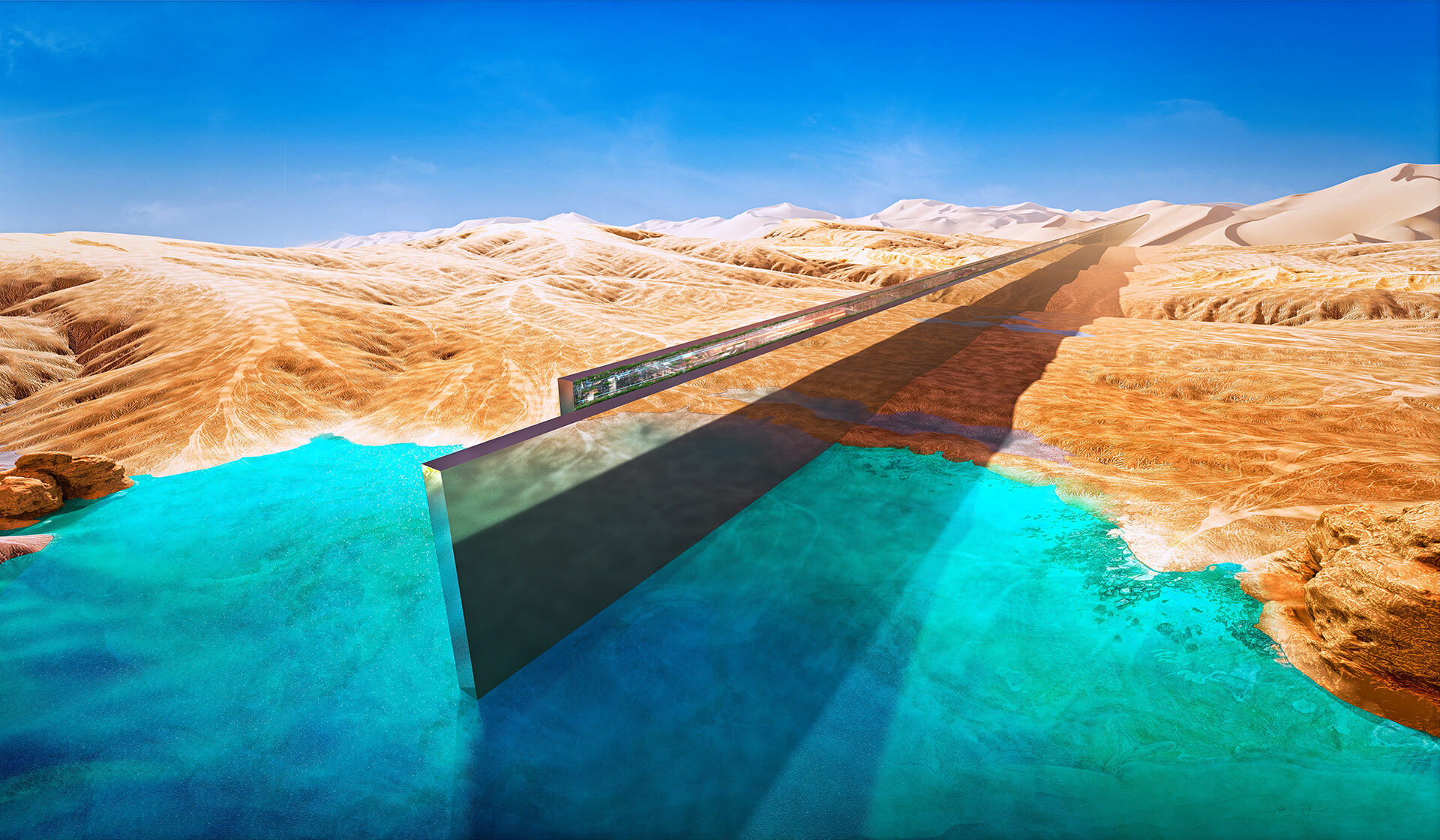

“Scratch” starts with an initial budget of $500 billion for NEOM, of which $200 billion has been earmarked thus far for The Line, a futuristic “linear city.” The money is coming from the kingdom’s sovereign wealth fund, which bin Salman runs. According to NEOM’s head of urban planning, “the first substantial population living on the LINE will be in 2030.” The project’s CEO claims that 20% of NEOM’s infrastructure has already been completed.

Who pays the piper calls the tune

Unsurprisingly, the crown prince’s gigaproject has served as the proverbial honey to flies for Western talent, offering large fees and the challenge of engaging in what the film asserts is “the biggest infrastructure project in history.” As one of the lead architects puts it, “every 40 or 50 years there is this great surgence where state, culture, politics, technology all converge into this singular, amazing unity of form.”

In Mohammed bin Salman’s kingdom, what has emphatically converged is an accumulation of power, previously unseen in Saudi Arabia, in the person of a ruthlessly ambitious prince. Bin Salman has control of virtually all the financial levers and has eliminated any potential challenges from within the ruling family, stripped the religious authorities of influence and imprisoned and executed critics who had dared to challenge him. There is only one client, one voice that the West’s leading architects and city designers have to win over to capture a share of the biggest and most expensive urban project the world has ever seen.

Peter Cook, who argues that much contemporary architecture is bland and boring and sees himself as an iconoclast, has embraced the opportunity with apparently little concern about the outcome: “If it succeeds, it will be the new Babylon, so to speak, and if it doesn’t succeed it will be an interesting phenomenon.”

Cook was asked at a NEOM-sponsored event in Venice in May if The Line would be built. He replied, “I’m going to give a very English answer. It’s an interesting possibility. You know, I think they’ll get a bit of it done.” He then went on to say, in reference to the proposed height of buildings designed to parallel each other along a 170 km-long line, “I think—I’m going to speak honestly now, as long as you don’t cut me off—I think higher than 500 meters is a bit stupid and unreasonable. and all our engineer friends will tell you this.”

He opined that 150 meters in height was “quite agreeable.”

Cook subsequently rowed back from the comments, telling the Architects’ Journal, “The discussion of ideas was informal, exploring the different height variables of The Line. After the Hidden Marina is built, I may eat my hat and say 500 meters is even more fun!”

Not everyone is so enthusiastic

The former British diplomat Arthur Snell offers a scathing corrective to the narrative of the Discovery Channel documentary in his Substack column. “The Line,” he writes, “remains happily fictitious, no more than an architectural fever dream.”

Snell, the author of How Britain Broke the World availed himself of Google Earth and imagery taken between 27–30 April this year to buttress his argument:

Zoom a bit closer to the ground and you’ll find that there is very little actual Neom in existence. A few isolated resorts and a golf course. No evidence of human habitation, or economic activity. Certainly not what could be called a city.

He notes that a photo posted online, taken in January,

shows a lonely filling station and a couple of fast-food joints, near to an encampment of shipping containers, a familiar sight to anyone who has visited the Gulf, used to house mostly South Asian migrant workers. The existence of the small camp shows that some construction work may be underway, but there is no evidence of a city being built.

Snell decries the indifference of Western governments and business to the egregious human rights abuses of the bin Salman regime, but he reserves his deepest contempt for what he sardonically calls “star architects” who, having

bravely rationalised their dislike of feeding bodies into incinerators, public beheadings and mass starvation in Yemen, along with other inbuilt features of MbS’s Saudi Arabia, don’t need to worry if their crazy designs will ever be built. They can earn astronomical fees dreaming up improbable cities, indifferent to whether a team of mistreated Asian migrant workers may at some future point be killed in their construction.

And there is another inconvenient truth that Peter Cook and his colleagues working on The Line have chosen to ignore. Contrary to bin Salman’s assertion that the space that NEOM and The Line are being built on is “empty,” some of it is in reality occupied by members of the Huwaitat tribe. When the tribe attempted to resist the arbitrary confiscation of the land, the response of the authorities was swift and brutal.

As reported by the London-based Saudi human rights organization ALQST, security forces shot Abdul Rahim al-Huwaiti dead in April 2020. He was killed in his home in Al-Khariba in a region of Tabuk province earmarked for NEOM after using social media to protest the eviction of local residents.

Three other members of the tribe were convicted in a specialized terrorist court and sentenced to death. Their appeal was rejected in January of this year. Other Huwaitat have been convicted in the same court and given lengthy jail sentences.

[Arab Digest first published this piece.]

[Anton Schauble edited this piece.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.