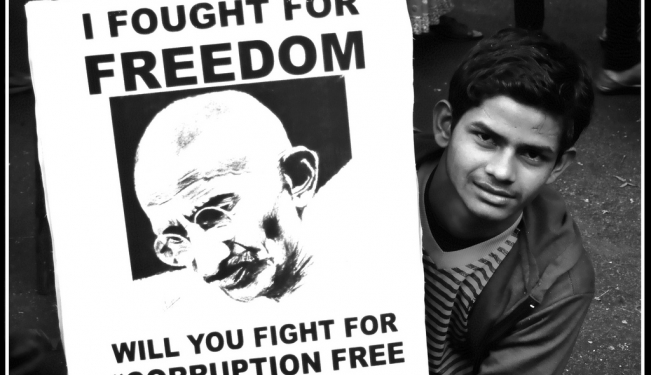

The cynosure of debates on corruption in the media trace its roots to the recent past, and lament lost business opportunities. Corruption is destroying more than just faith in politicians or killing business opportunities or tarnishing India’s image. It is wearing away the adhesive that hold the country together.

Because India was posited as a nation-state post independence, corruption developed a strong foothold in Indian politics. Educated in the west, enamored by the French revolution, and armed with strong notions about ameliorative ends of the Indian state, India’s founding fathers cobbled together a federation of former kingdoms and provinces. The shared trauma of partition and an excitement about the sheer enormity of possibilities freedom provided the binding glue for the Indian nation in 1947. Throw in myths of a common history and the demands of political expediency, and we have the birth of India as a nation; a nation with a common history, and a common future. Symbols like the national anthem that spoke of the diversity of India and Gandhi as the father of the nation were devised to reinforce the idea everyone who lived within the geographic bounds of the country had something common that made them uniquely Indian. The legislature, judiciary, the military, and the executive were merely necessary instruments that helped in governance. This formed the state, and hence the idea of the nation-state.

Although envisioned as a nation-state, India, for vast sections of the population, remains a perverse state-nation. For swathes of Indians who were unable to understand the project of constructing a nation, India simply came to be understood through interactions with representative agents and symbols of the state – the village council, the district magistrate, and so on. The idea of India to most people continues to be that of file pushers and politicians. All we can see and understand are symbols of the government, and therefore the state. The idea of a nation, the idea of a past and future shared with 1.2 billion more people, comes next. It certainly is difficult for a farmer in Manipur to identify with a city-dweller in Kerala. To understand India thus, as a state first and then as a nation, is crucial to understanding the true cost of corruption in India.

Nehru and Gandhi, both moral behemoths from whom politicians still draw legitimacy, lent their support to the politics that ran India in the first decades post independence. This allowed politicians to assume the position of rightful distributers of the good the state was to deliver. With the state and its agents in every administrative district, it could not have been long before violations of norms and standards of conduct took place. Even within the first few years post independence, corruptions became a cause for political bickering. In the 1950s, Ram Manohar Lohia railed against Nehru’s inappropriate liaisons – the belief that corruption is a relatively new phenomenon is therefore flawed. Consequently, in the six decades post independence, most Indians came to imagine the state through bribes paid to the district magistrate’s clerk or adulterated kerosene. Corruption came to be accepted as an indispensable part of life.

Until the 1990s when India was forced to liberalize its economy, arguments for the efficacy of corruption were bandied about. For example, the practice of bribing politicians and government officials for licenses to set up industries was explained as rent-seeking behavior that created an efficient market for licenses. Corruption, certainly in the case of allocation of licenses, did not necessarily lead to the optimal projects being authorized. Morality and rent-seeking are not the best of bedfellows.

Since the 1990s the Indian economy has grown rapidly, and the age of opportunities that followed has brought about deep social change. Corruption has become more pervasive and arbitrary than ever before. Strangely, India’s much lauded democratic system has had a role to play in the rampant spread of corruption. Over the last few decades, Indian democracy has become more and more inclusive. There has been a rise of coalition governments, and voting based on ethnicity. Social movements that aimed to uplift sections of the population have come to legitimize corruption, albeit in a backhanded way. Corruption has become a key channel for social mobility, and in this sense, has even come to enjoy a form of social legitimacy. When India’s former Telecom Minister was implicated in the scandalous spectrum auction scam in late 2010, demonstrations were held in his home state of Tamilnadu decrying allegations of corruption. The former minister, the demonstrators felt, was being singled out because he belonged to a particular social group!

Given the profusion of scams that seem to have come to light in the last 12 months, it is tempting to assert that Indians are, by nature, an amoral people liable to be corrupt easily. However, research has shown that Indians are just as liable to be corrupt as their peers in developed countries in Asia. What sets Indians apart is their willingness to tolerate corruption. Perhaps, given India’s peculiar position as one of the fastest growing economies with one of largest populations of poor people, one must step down from the moral pedestal and allow for a more socio-economic understanding of the phenomenon of corruption. Perhaps, one cannot help but pass off daily encounters with a corrupt state as mere inconveniences. But what of the mega scams of recent years? What of senior jurists and army officials, a class of public servants hitherto considered largely incorruptible, being implicated in scams? The very existence of India as we know it is at stake.

The durability of the liberal-democratic Indian state is a lie. People have argued that Indians might lose faith in their politicians for too long, but never in the state. Myths about states, their founding fathers, and institutions weaken over time. Partition and freedom are now distant memories. Gandhi and Nehru hold no sway over the modern Indian. The idea of India as a nation was never strong from the beginning. And whatever is left of that notion is clearly being challenged from within. New identities are emerging, and movements against the imagined-state, like demands for greater federalism, are well entrenched. What keeps India together, for most part, are only institutions of the state. Belief in the state is beginning to wane as well, and the recent expansion of the Maoist movement is a striking, though extreme, case in point. In a country with an increasingly younger demography sold to the dream of riding the wave of India’s economic growth, recent scams have only sowed seeds of discontent; a disgruntlement with the state and its apparatus. Corruption, it seems, is quickly eroding belief in the state. If belief in the state were to vanish, India, the nation-state that never was and the state-nation that is, will cease to exist. Will India splinter into a hundred nations? Only time will tell, but the possibility that it might is very real.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 3,000+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment