An overview and analysis of efforts to bring democracy to the Middle East.

On February 15, 1991, in the aftermath of the First Gulf War, President George H. W. Bush announced that “There is another way for the bloodshed to stop. And that is, for the Iraqi military and the Iraqi people to take matters into their own hands and force Saddam Hussein, the dictator, to step aside.” This statement encouraged thousands in the predominantly Shiite southern region of Iraq to rise against the dictatorship of Saddam Hussein. The Iraqis expected that their uprising against the authoritarian regime of Baghdad would be supported by the United States. It was not, and the uprising was put down brutally by Saddam Hussein. Saddam subdued the opposition and conquered the South with an unprecedented level of cruelty and carnage.

President George W. Bush invaded Iraq in March 2003 with the presumption that Saddam was a threat to the United States and the world through his pursuit of weapons of mass destruction. As these presumed weapons were not found, the mission changed to democracy promotion in Iraq. President Bush viewed democracy promotion as a critical instrument in the long-term war against terrorism. This “coercive democracy” strategy involved invasion and occupation and it became the corner stone of American foreign policy under his administration. He stated in December 2006, “[We] are committed to a strategic goal of a free Iraq that is democratic, that can govern itself, defend itself and sustain itself.” The “war on terror” encouraged the Bush administration to heavily invest in authoritarian regimes throughout the Middle East including Mubarak in Egypt and Salih in Yemen. They became partners in Washington’s war against terror. They later convinced the United States that Washington’s support of their regimes would lead to their stability and strength and would colossally benefit the strategy of the administration in the war against terrorism. For that reason, Washington strengthened its ties with these regimes, ignoring their brutality against their own people and their violation of the rights and freedom of the citizens of these nations.

In June 2009, President Obama declared in his Cairo speech, “Each nation gives life to this principle (democracy) in its own way, grounded in the traditions of its own people. America does not presume to know what is best for everyone, just as we would not presume to pick the outcome of a peaceful election. But I do have an unyielding belief that all people yearn for certain things: the ability to speak your mind and have a say in how you are governed; confidence in the rule of law and equal administration of justice; government that is transparent and doesn’t steal from people; the freedom to live as you choose. Those are not just American ideas, they are human rights, and that is why we will support them everywhere.” This speech raised hope in the Middle East and the Muslim world as many speculated that the United States intended to change the course of its foreign policy to one in which it would support democratic movements and end its support of authoritarian regimes, especially in the Middle East. With high hope for change following President Obama’s speech, many were disappointed later to observe no change in Washington’s relations with the authoritarian regimes of the Middle East. Middle Eastern people, specifically, lost hope in the notion that the United States would genuinely support democratic change in the region and become involved in the initiation of peace throughout the region.

More than anything else, the example of Turkey rather than Iran has inspired many in the Middle East over the last decade to strive for democratic changes, and many believed that democratic change would be possible both under secularism and Islamism. Although Muslims participated in establishing stable democratic societies and governments in countries such as Malaysia and Indonesia and actively participated in democratic politics in countries such as India and in the other parts of the world, a group of scholars in the West, before and after the introduction of the “clash of civilizations,” concluded that the countries of the Middle East are not capable of and adept at embracing democratic norms because their predominant religion, Islam, is not compatible with democracy. Human rights, democratic norms, women’s rights and participatory politics were considered the sole monopoly of the West and alien to this region. This tendency that was called neo-orientalism in the literature of the region shared its conceptual framework with past orientalists who separated Orient and the West in the realm of culture, society, politics, modernity and civilization.

Authoritarian regimes of the region were occasionally open to discuss their belief that people of the region were not ready to embrace democracy. Umar Suleiman, the Egyptian politician who was chosen by Mubarak to rescue his regime in the last days of the Egyptian revolution, contended in one of his interviews that Egypt was not ready for democracy. For their own reasons, authoritarian regimes in the Middle East share with the neo-orientalists the belief that since democracy cannot take root in this region, they are the best fit for government.

Disappointed with Washington’s policy toward the region, especially in regard to encouraging democratic change, and demoralized by the level of brutality and disrespect these regimes showed for the basic rights of their citizens, the Arab youth began to force change in these nations. However, contrary to the perception that tends to amplify the role of economy and unemployment as causes of change in the Middle East and North Africa, the Arab Spring Revolutions pondered on the rights and modern notions of self government through the rule of law, accountability and participatory politics. The revolution started in Tunisia, a North African country of ten million people. The spark came with the violation of the rights of Mohammad Bouazizi who protested against the authorities who affronted him and seized the sole means of his and his family’s sustenance. Bouazizi set himself ablaze in the city of Sidi Bouzid on December 17th, 2010 in protest of the injustice and violations of his rights by the Tunisian government. The dictatorship of Tunisia under Zein al-Abideen Ben Ali collapsed after 28 days of continuous protest in January 14th 2011. His dictatorial rule ended after 23 years in power.

The Egyptian revolution inspired by the Tunisian revolution and the process leading up to it began on January 25th, but the seed of the Egyptian revolution had also been planted by Khalid Mohammad Said, a 28 year old Egyptian who died mysteriously under the custody of the police in the Sidi Gaber area of Alexandria on June 6, 2010. He was apparently beaten to death by Egyptian security forces. Photos of his disfigured corpse were disseminated on the internet and a prominent Facebook group raised awareness about his death with the slogan, “We are all Khalid Said.” The Egyptian youth involved in the April 6 Movement, the We are Khalid Said, , the Kefaya Movement and others called for mass protest on January 25th with simple requests of the Mubarak regime, which included ending the state of emergency, dismissing the interior minister responsible for the government’s violations of human rights, establishing an independent judiciary system, carrying out political reform, dissolving the parliament in anticipation of a fresh new election and addressing poverty and unemployment. In a country with a population of 85 million, and with millions participating in the protest, it took 18 days for the collapse of the regime of Mubarak who ruled the country arbitrarily for 30 years.

On February 15th, 2011, people in the mostly desert and tribal country of Libya with a population of 6.5 million, marched to free a human rights lawyer, Fathi Terbil, who was representing the families of the political prisoners being held at Abu Salim prison in the southern city of Benghazi. The revolution began against the brutal regime of Qaddafi who ruled the country for 41 years. In the same month another revolutionary upheaval began in Yemen against the dictatorship of Ali Abdullah Salih who ruled the country with an iron fist for 33 years. In Bahrain, the al-Khalifa family ruled the country since the 18th century and for more than two centuries. The minority Sunni population ruled over the majority Shiite population without respecting the rights of this majority to participate equally in the politics of the nation.

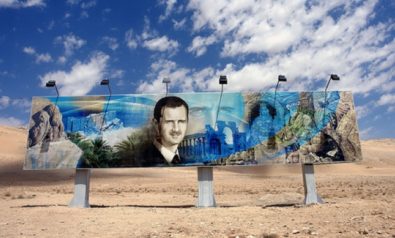

Beginning in the middle of March, the Syrian government faced revolution and upheaval in the city of Daraa. The regimes’ brutality can only be compared with Iran in suppressing the Green Movement after the 2009 fraudulent election and Libyan leader Muammar Qaddafi after the rise of opposition to his despotic regime starting in February. These three regimes have shown that they will not hesitate to resort to violence in achieving the ultimate goal of suppressing dissent. In February 1982, the Syrian government under Hafiz Asad massacred thousands in Hama, a city on the bank of the Orontez River in central Syria. People also rose up against the monarchies of Jordan, Oman, Morocco and in new Iraq, demanding their rights that were violated by autocratic rule and rulers who denied their citizens’ rights to political participation and democratic norms in government and society.

The Arab Spring Revolutions were aimed at two crucial problems in the politics and society of these nations that underwent and are currently undergoing transformation. Arab dignity and rights were at the core of the demand for change. Dignity in the convoluted history of these societies has a very distinct meaning and inference. Most of the countries of the Arab world have not experienced independence and freedom in the modern history of their nations in almost 150 years. In the case of Tunisia, the country was colonized by the French in 1881. An independence movement against colonial rule prevailed in 1954. But still the country stayed under indirect colonial rule under which the French controlled its army and foreign affairs according to an agreed convention created in 1955. On March 20, 1956, Tunisia achieved full sovereignty but the French imposed on it a monarchical system. Finally in July 1957, the monarchy was abolished and Habib Bourghiba under the Neo-Dastour Party took over the country as its president. Bourghiba was an autocrat who was fully supported by the French. After Bourghiba, Ben Ali ascended to the helm of power in November 1987. Both Bourghiba and Ben Ali had ties to the military and were supported by their French patrons. They ruled the country arbitrarily and incessantly crushed dissent and demands for rights and political participation.

In 1860, Khedive Ismail in Egypt took advantage of the vastly inflated cotton price as a result of the American Civil War. He attempted to build a modern economy, but his hopes were dashed as the economy was badly mismanaged and cotton prices dropped in the global market. As the result of deterioration in the economy and over a loan of 976,587 British Pounds, the British took over control of the Suez Canal. Egypt indebtness encouraged other Europeans to extract more concessions from the country. In 1879, Egypt was placed under the dual control of the British and the French. Ahmed Urabi, a military officer, revolted against the British and the French. He became the leader and the symbol of anti-colonial movement in the country. In 1882, the French and British fleets were brought to Alexandria to ensure the security of the Suez Canal. The British bombarded the city and suppressed the nationalist uprising led by Urabi. The British stayed in Egypt until 1956. In July 1952, a group of military officers under the leadership of General Mohammad Najib overthrew King Farough. Naser came to power and later nationalized the Suez Canal.

These three countries, similar to many others in this region, were ruled by the military directly or indirectly after a prolonged period of colonialization. The brutality of colonial control took away the sense of security in these societies as seen today. Only the military could have responded to this sense of insecurity. But as military regimes took over in these societies, they ruled with an iron fist and total impunity. This new sense of insecurity coupled later with the insecurity that these people and regimes experienced during the Cold War between the former Soviet Union and the United States. The establishment of the state of Israel in 1948, the tensions of war and conflicts, in addition to the United States’ support for the most authoritarian regimes of the Middle East during the Cold War, left no room for the countries of the region and their people to debate pertinent political issues in government and society and did not give the people of these countries any chance to establish civil societies in these nations. Armed with the support and arms of the United States and the West, regimes such Sadat and Mubarak expanded their arbitrary rule and control of these societies. When Arabs talk about dignity, they talk about the dignity of generations that was robbed, under colonialism, war and conflicts of the Cold War. A Generation that lost its grip on debates over democratic norms in politics and society and spaces in which it could establish the bounds of a free and democratic society.

The Arab Spring Revolution has been carried out by a generation that is young and highly educated. This generation is very idealistic and persistent. It includes both young men and women, determined not to compromise on certain principles, rights and democratic norms for which they carried out these uprisings and revolutions. Among all, the Egyptian model shows much more resilience and persistence compared to other current transformations. The youth took ownership of the revolution from its early inception. At the onset, the youth of Egypt did not know what the outcome of their uprising would be but during the course of the uprising, they understood the limits of their demands, the kind of pressure they could exert on the government and finally how to mobilize to achieve their goals. They demanded the banning of Mubarak’s National Democratic Party, the dissolution of all local councils, the replacement of the governors, the arrest and trial of certain notorious figures in the previous government and finally the arrest and trial of Mubarak and his sons who were co-conspirators in their father’s corruption and tyranny. They have achieved most of these demands and continue to push for the rest. Their persistence and participation could guarantee fair and free elections and more than that, could bring about their full participation in the politics of the country.

Taqadum al-Katib and Asma’a Mahfouz, two of the youth involved and a male and female respectively, were among the organizers of the uprising. From the early days, they broke the barriers of gender in the politics of a country that is experiencing a new era in participatory politics. This is perhaps the first time in the history of modern Egypt that women have been involved to such a great extent in shaping and molding the new politics of political participation. This has signaled a new era in gender relations in a society where barriers to equality between the male and female have existed in the past. This transition to a modern era will open the door to greater opportunities for all Egyptians to equally respect participation in rebuilding a new polity and society.

The Spring Revolutions, especially the Egyptian model, broke the monopoly on information as exercised by one group in society. The youth’s skills in managing social media and ability to mobilize through this medium totally incapacitated an authoritarian regime that monopolized the dissemination of information in that society. Although the regime of Mubarak diligently attempted to constrain access to social media, it lost that battle to the youth who knew better how to manage it. Although the precedent established in this area by the youth of Egypt does not guarantee the freedom of information and expression, it could usher in a new era in the politics of Egypt if coupled with their persistence. The Egyptian youth and all youths involved in the Arab Spring Revolutions have understood the importance of freedom of expression and freedom in accessing information. This offers a greater incentive for them to safeguard these freedoms in the process of building strong civil societies in their countries.

Egypt, like Turkey, had a long history of military involvement in politics. The predominance of an insecure environment both in Egypt and countries such as Tunisia led to domination of military regimes. These environments do not exist either in Egypt or in other countries such as Tunisia for the military to intervene. There is also the well established norm of non-violence that was adhered to from the beginning of all of these revolutions and great transformations. These movements well understood early on that if arms were used in winning the battle for change, the winner would always be the regime that has more power and expertise in using violence and intimidation. These peaceful revolutions disarmed regimes which intended to provoke a violent reaction. Such tradition of non-violence, coupled with the persistent efforts in participation in politics and the shaping of a future civil society, will undermine any efforts at resorting to violence and arms in these societies. As new civilian governments are established and people are encouraged to stay the course in reshaping their government, the military will continue to lose its ability to impose itself on the political processes. These revolutions, especially the one in Egypt, learned how to neutralize the army. The cases of Libya and Bahrain are different in that the people are being ruled by desperate individuals seeking to hold power at any cost and in the latter case, the country is currently being occupied by foreign forces that are aiding in suppressing revolt. These foreign forces from nations neighboring Bahrain are afraid of the future changes in this country that could ultimately jeopardize the political stability in their own nations and especially undermine the rule of monarchy in that part of the world.

These revolutions have also succeeded in dismantling the foundation of ethnic and religious discrimination and division. The participation of women and their leadership in these uprisings, especially in Egypt, have changed gender relations. Similarly, the participation of all religious minorities, particularly the Coptic Church in Egypt, has changed another social dimension in these countries. The new alliance forged for change will help these nations deal more effectively with gender, ethnic and religious differences. The new dawn in the politics of these nations will question old mores in society because the youth are at the forefront of these changes. The youth revolutionaries have defied the old perception of division and defeated discrimination in these nations. In Egypt, the younger Muslim Brothers split with the old guard because their demand for change was much more profound and inclusive than their predecessors. In almost all countries of the Middle East, the demand to separate government from religion and to shape inclusive pluralistic politics is well known. The experience of Iran and the level of tension that the Iranian political model and government has created internally and externally are obviously well observed in the Arab world. Although involved in the Arab revolutions, none of the religious groups were convinced or encouraged to receive credit for many of these great transformations. The culture of pluralism and inclusiveness is developing through the societies under these revolutionary changes.

The authoritarian regimes from the Shah of Iran, to Mubarak in Egypt, were heavily involved in westernizing their societies at the expense of genuine modernization. Modernization of economy demands modernization of politics and society. The lack of interest of these regimes in engaging in a genuine modernization scheme, alienated the majority in these societies. Although few societies have succeeded in establishing a modern economy as China has done, for instance, the risk of alienation and opposition to the dominant politics is always present. In the Middle East, it has been proven repeatedly that true modernization means a change in economics, politics and society’s institutions. The Arab Spring Revolutions could usher in a new era in modernizing all aspects of these societies. With a new generation on the forefront of these efforts, this is a crucial chance for all of these countries to use this energetic and intellectual resource for the welfare of their societies.

Although these revolutions did not subscribe to any particular ideology, the sense of nationalism and pride is pervasive in all of these nations. Nationalism and its promotion in the past belonged to military rulers who took advantage of the perception of insecurity in these societies and ruled arbitrarily. The new nationalism is a grassroots effort and not elite based. It involves patriotism and pride that are based on the idea that through collective efforts, modern society and its institutions can be built. These societies are dedicated to democratic norms, respect for rights, a commitment to the rule of law, accountability, and a pluralistic participatory political model. During the period of their revolution, Egyptians were continuously declaring their pride in being Egyptian. That sense of pride, which was based on their achievement of establishing a free society, could be maintained for positive engagement in a new political experience. Modernity and modern society for the revolutionaries in the Middle East means a break with the past in which colonialism, authoritarianism and foreign influence brought into being societies, politics and governments that alienated them and took away from them any sense of security and pride. With efforts aimed at establishing viable, accountable governments based on democratic norms, the Arab Revolutions could build new societies in which their dignity and pride will be restored.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a sustaining member.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.