The way that the United States and China currently spend their healthcare dollars differs sharply.

In China, about half of healthcare spending is on pharmaceuticals, while in the United States only 10% is. Both nations are in the process of undergoing healthcare reform. While America is implementing the Affordable Care Act, aimed at decreasing healthcare utilization, China is implementing its 12th Five-Year Plan, which contains a number of healthcare provisions aimed at increasing healthcare utilization. Given the policies currently being pursued by both nations, it is likely that their pharmaceutical spending patterns will head towards convergence, with Americans spending a relatively larger share on pharmaceuticals, and Chinese spending a relatively smaller share.

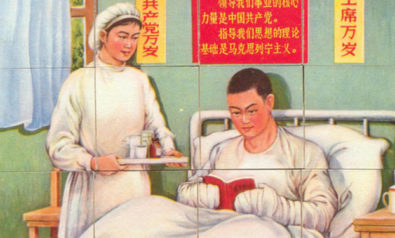

Historically, the American and Chinese healthcare systems have had somewhat different strengths. The American system has relied on using highly-trained clinicians to provide expensive reactive care to a small percentage of the population, while the Chinese system has relied on using clinicians with wider variation in training to provide care that is more focused on prevention and is more affordable. This dissimilarity in provider infrastructure is one of the causes of the different use of pharmaceuticals in the two countries.

As a result of the different focuses of the two healthcare systems, healthcare spending is 17.4% of America’s GDP and 4.6% of China’s GDP. Heavy reliance on pharmaceuticals can lower healthcare system costs, as generics have almost no marginal cost, and it often costs less to administer pharmaceuticals than the physician services they sometimes replace. For instance, antidepressants are a lower cost, albeit imperfect substitute for some forms of psychiatric services. Pharmaceuticals likewise can be administered with less training and time. While often cheaper, pharmaceuticals do not always provide better outcomes than physician services, and often carry side-effects.

China’s reliance on pharmaceuticals has multiple origins. While high pharmaceutical use is in part motivated by the design of China’s healthcare delivery system, there are also other factors at play. Currently, Chinese public hospitals (the vast majority of hospitals) operate under price controls. Prices will need to be increased in order for hospitals to be able to sustain themselves solely on healthcare services. While physicians cannot officially charge more than the set prices to patients, they can derive revenue from other sources. One legal source is through the sale of pharmaceuticals. While American physicians cannot dispense the drugs they prescribe, Chinese physicians currently can. This has created a financial incentive for overprescribing which may be impacting treatment decisions.

Recognizing this issue, the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China has called for the separation of dispensing from prescribing in public hospitals in its 12th Five-Year Plan, which guides policy development from 2011 to 2016. Although the integration of dispensing and prescribing makes sense within the context of Traditional Chinese Medicine due to the personalized nature of treatment, it has become clear that it is problematic within the context of allopathic medicine. While this separation will have a substantial financial impact on Chinese hospitals, Minister of Health Chen Zhu is working to ameliorate this problem through increasing the schedule of prices that hospitals may charge.

Meanwhile, in the United States, pharmaceuticals are becoming more affordable to Americans, as the Affordable Care Act increases prescription drug coverage for both seniors and the poor through requiring insurers and drug manufacturers to provide rebates and greater cost sharing. Growing access to health insurance without commensurate growth in the number of physicians is creating a physician shortage. As a result, Americans may have to rely on a more varied set of providers, as Chinese do today. Pharmaceuticals may likewise play a greater role both due to the substantially lower cost of generics relative to physician services, and due to the shortage in physicians available to provide services. Thus, America’s use of pharmaceuticals may become more Chinese while China’s use of pharmaceuticals becomes more American. Moving forward, lessons from China’s past may increasingly become relevant to America’s future.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment