Only rule of law and a culture of diversity can overthrow autocracy and religious fundamentalism in the Middle East.

One fundamental problem for Middle Eastern countries is that a majority of the rulers are illegitimate. While each country has its own history and trajectory, common patterns prevail across the region: Those in power have not received their positions from a fair and transparent electoral process. They see themselves as above the law and misuse their absolute power.

These autocrats act as a guardian of the people or treat them as an enemy. Sets of tribal and religious convictions replace law in many countries in the Middle East and North Africa, and power is fundamentally linked to tribalism or religion.

How have power struggles, religious conflict, discrimination, security issues, colonialism and Western hegemony, values and intervention shaped the Middle East? This author spoke to PhD students, academics and university lecturers to learn more.

Muhammad Waladbagi, a PhD candidate at Durham University working on Turkey-Iraqi Kurdistan relations, states that the modern history of the Middle East has witnessed frequent interstate wars, numerous revolutions, coup d’états, civil wars and economic problems:

“These are signs of fundamental problems in the region’s political culture that at times has set the ruling regimes against their people. It is quite difficult to identify and explain the reasons behind such phenomena in a few sentences as the origins of the problems differ in each specific case, and Middle Eastern states are not homogeneous as they have many differences.”

The role of religion

The feeling of attachment to tribalism and fake patriotism under the umbrella of religion is stronger and more apparent than respect for human rights and pluralism in the Middle East. Patriotism is used as a tool to accumulate wealth and oppress the rights of minorities, while religion and tribalism are often militarized, making the use of violence legitimate and normal.

Sabir Hasan, a lecturer at the University of Human Development and a PhD student at the University of Leeds, says religion—specifically Islam—is an inseparable part of Middle Eastern society, and it is one of the most influential domains of Kurdish social life:

“It is not surprising that different tribal and so-called patriotic groups resort to religion to gain legacy and popularity. As for ‘fake patriotism’, as you termed it, we need a simple glance at the contemporary history of Middle Eastern regimes, including Kurdistan, to see what abuses and scandals have been committed in the name of patriotism. It is axiomatic that those who first claimed to be loyal patriots have eventually become millionaires, all at the expense of the public. Those who misuse religion and patriotism can be regarded, at best, as opportunists.”

In a region where exchange of power often causes destruction and chaos, the psychology of the rulers is structured in such a way that they consider themselves to always be right, thus there is no need for an election. Humans are not seen as humans, but as either friend or foe. Ironically, one has to act like an enemy to be a friend and a friend to be an enemy. That is to say, one has to be the enemy of freedom to be the friend of an oppressor, and to be a protector of an oppressor to be the enemy of democracy.

Power struggles

Analyzing the issue of power struggles from a psychoanalytic perspective, Mohammed Akoi, an assistant lecturer in Raparin University in Sulaymaniyah, says:

“Sigmund Freud talks in detail about the Oedipus complex; that is, the unconscious rivalry between the father and the son. I see a similar type of complex when it comes to rulers in the Middle East. There is a myth in Kurdish folklore that could say a lot about father-son rivalry in the Middle-Eastern context.

“The story goes that a father, after having lost all his sons but one, arranges a wedding for his last son, Saidawan. As the party ends, Saidawan goes hunting to the mountains, and so does his father. Saidawan dresses in a wild goat’s clothing in order to attract other goats and thus hunt them. His father, on the other hand, seeing a supposed wild goat and not knowing it is his son in disguise, kills him and thus loses his last son.

“The story is often told as a tragic misfortune on the part of the father. However, approaching the incident from a Freudian interpretation, it is the father who kills his son unconsciously. Much has been said about the Middle Eastern father as an example of divine authority who is always there to punish the son.”

Akoi argues that rulers in the Middle East play the role of a typical superior who enjoys the authority of the father. Therefore, it comes as no surprise that democracy, the product of Western consciousness, always fails to shake the Middle Eastern father’s position.

The dictators of Middle Eastern countries see armed struggle as a pathway to their eternal need for power. Instead of promoting coexistence, they embrace war and military confrontation; instead of building legitimate institutions, they destroy the country’s infrastructure; and instead of organizing an inclusive, lawful military force, they establish militia units for the sake of adding fuel to the sectarian disputes. This paves the way for the dictators to remain in power as long as they want or until they are forcefully deposed.

For Sarkawt Shamsulddin, a political analyst at the Kurdish Policy Foundation specializing in governance and security and NRT TV’s bureau chief in Washington DC, two issues are of pivotal importance: the abuse of religion and a lack of good governance. The focus here is on governance.

“The rulers in the Middle East have been oppressing their people for decades and they have used different means to do so, such as undermining human rights, democracy, freedom of speech and civil society as a whole. They have undermined opposition groups. They have mostly invested in military and security institutions. Therefore, when revolutions or what is called the ‘Arab Spring’ emerged, they use their military capability to stay in power.”

In the underdeveloped countries of the Middle East, security and military forces are dominated and ruled by tribal chiefs and religious figures. Infringement of political rights is authorized through elastic rules, and the confiscation of democratic values is fallaciously considered a religious duty. The public sphere is in total chaos, and the government has too much influence through the media, economy, education and even on the private lives of the people. This abuse of power has become an inherent part of governments’ mechanism to uproot any kind of freedom—be it freedom of speech, freedom of expression, freedom of conscience or freedom of the press.

Zubir Rasool, a PhD candidate of Middle East politics at the University of Exeter, argues that there are numerous problematic issues that can contribute to the structure of current conflict in the Middle East. The main issue in this regard has to do with the structure of the so-called “nation-state” on the one hand, and its political, social and economic functions on the other hand.

“The evolution of the nation-state did not come from a natural process in the Middle East. Large groups of Middle Eastern countries were the results of colonial operations—whether it was from the Ottoman Empire or European colonialism. Both of these historical moments’ legacies share a responsibility for the creative chaos in the Middle East nowadays. The terms nation-building or state-building was just a figurative cover for the combination of different ethnic, tribal, linguistic and cultural identities. The legacy of the Ottoman Empire is based on the distinction between Muslims and non-Muslims; also, non-Muslims were divided among their ethnicities and religious sects.”

The middle-class has deteriorated and the professional workforce is almost non-existent. A lack of public facilities, low income and high unemployment keep people frustrated. A lack of food quality and stable electricity, poor health care and stagnant education keep people over-occupied and struggling. This way, people do not have the means to revolt. They are more occupied with providing the basic needs to survive, let alone the strenuous dangers of migration and the perpetual challenges of resettlement, identity, discrimination and cultural integration.

Refugees

Ramyar Hassani, a human rights observer in Latin America, Europe and Kurdistan, says that in a Middle East that is burning because of sectarian wars and extremist organizations, being a refugee has become a normal phenomenon.

“On the one hand, the proxy wars of regional powers have forced thousands of Middle Easterners to flee and leave everything behind. On the other hand, the wrong policies of Western and world powers led the Middle East into a clash of extremists, which resulted in thousands of refugees [heading] to a safer country [and] dreaming of a life without violence.”

With that in mind, whenever there is a revolution, the faces change, but the mentalities are the same. That is to say, a new despotic clan will take over power, establishing the same sort of mechanism to replace and then rule in the same manner as the ousted autocrat. Each clan or tribe controls a certain territory with their own armed force and militia in hand and their own rules in place.

That being said, constitutional legitimacy is threatened by political outbidding and revolution. The legitimate exchange or handover of power and social justice are vulnerable in the face of political and economic corruption, which is why disorder, instability and war have always been part of the autocrat’s culture and mentality.

Sherko Kirmanj, a visiting senior lecturer at the University of Utara Malaysia and the author of Identity and Nation in Iraq, believes the question of legitimacy is one problem that faces the Middle East.

“One of the major problems confronting Middle Eastern societies is that the process of modernity in the region is not home-grown, but rather an imposed one. Modernity with all its dimensions and outcomes, including the nation-state, secularism, democratization, freedom, etc, were alien concepts introduced into Middle Eastern societies in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The introduction of these concepts and the values that embrace such equality, justice, fairness, freedom of speech and freedom of religion—just to name a few—led to a clash with local and traditional values of these societies.”

In the End

Western leaders and institutions have a limited understanding and familiarity with Middle Eastern societies, cultures and politics. This often leads to a focus on increasing arms and ammunition supplies and offering military training, especially in times of a violent insurgency, instead of the much-needed humanitarian, educational and developmental aid. This creates an ongoing cycle, wherein whoever has the most military strength holds power and steps into the same pattern of governmental rule.

What has blinded the West is the age-old misconception that Middle Eastern societies are anti-civil society, anti-democracy and anti-multiculturalism. This thinking leads to the conclusion that these societies are doomed to remain in bloodshed, where the best treatment is the importing of more and more weapons. This approach fails to address the root problems and instead contributes to the cycle of violence.

The West must realize that the real danger lies in the empowerment of religious fanatics and systemic corruption that have replaced true critical thinking, quality education and effective institutions.

By publishing and glamorizing radical groups’ propaganda on media platforms such as YouTube, the West can demonstrate how significant a culture of diversity and rule of law is for consolidating democracy. These two elements—rule of law and a culture of diversity—are the only means through which autocracy and religious fundamentalism can be overthrown.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

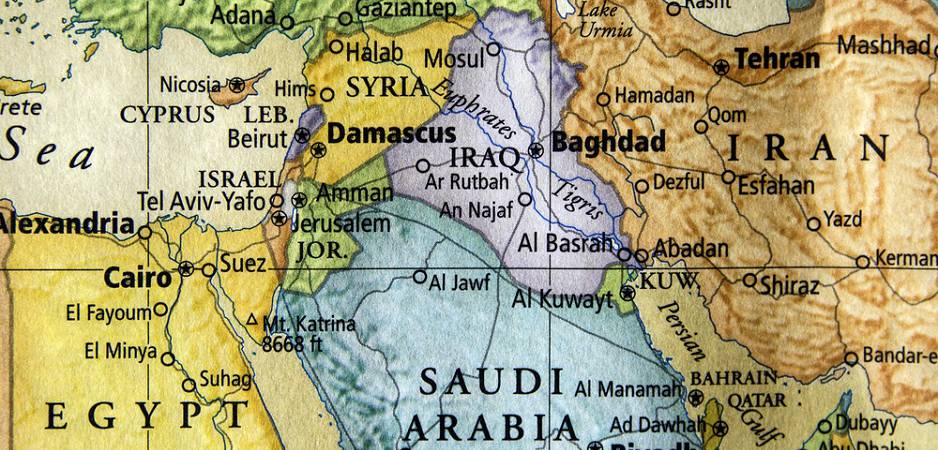

Photo Credit: Robert Hale / Strels / Shutterstock.com

We bring you perspectives from around the world. Help us to inform and educate. Your donation is tax-deductible. Join over 400 people to become a donor or you could choose to be a sponsor.

We bring you perspectives from around the world. Help us to inform and educate. Your donation is tax-deductible. Join over 400 people to become a donor or you could choose to be a sponsor.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment