The constant fear of death has transformed Syria’s secular Sunnis into warriors of God. [Read part one here.]

Whether it is the thump of barrel bombs, the indiscriminate artillery barrages or the sniping of innocent bystanders — to name only a few — Syria is rife with testaments of human mortality. For Syrians, the contemplation of death is a harrowing daily thought experiment; the crux of which concerns the uncertainty of one’s posthumous self.

Do things just go “black” when we die? Is death that anti-climatic? Unfortunately, these vexing ruminations only conjure up others: What is the meaning of life? or what are we doing here? All of us confront these questions throughout the course of our lives. But for Syria’s downtrodden, whose lives may not reach tomorrow, their poignancy is superlative. These questions need to be answered — and now; not only to “manage” the paralyzing fear death, but also to find meaning amid the emptiness of life.

Terror Management Theory (TMT) posits that humans, prompted by reminders of death, derive existential balms from cultural world-views that “provide meaning, purpose, value, and the hope of either literal or symbolic mortality, through either an afterlife or a connection to something greater than oneself that transcends one’s mortal existence.” More prosaically, “there are no atheists in a foxhole.” Christians find comfort in the belief that Jesus will admit them to heaven, while Jews believe that by following the Torah, they will be granted eternal life with a seat at God’s VIP table.

Unsurprisingly, the ontological clarity and definiteness such narratives bestow have arguably made religion the most resorted-to existential salve. Numerous studies have showed that mortality salience (reminders of death) increases participants’ “investment in core religious symbols, self-reported religiosity, and their belief in divine intervention.”

Accordingly, by embracing religious verities and conforming to their norms, one joins an exalted in-group with a sanctified cause and a monopoly on eschatological truth: a higher purpose to live for, and thus, the transcendence of death.

Looked at through the lenses of TMT, Syria’s Salafi awakening is demonstrably a natural psychological response. Syrians desperately seek existential buffers that soothe the relentless fear of death.

Ontological aplomb, therefore, allows an individual to muse his or her expiration date or — in some circumstances — stare it in the eye and maintain equanimity. Charged with a divine purpose, and operating under the aegis of God, a perceived immortality of the self is fostered. Although sacrifice for the cause may entail corporeal demise, one’s spirit will live on in the “grateful or admiring memory of others” — and in the paradise of the world to come.

Looked at through the lenses of TMT, Syria’s Salafi awakening is demonstrably a natural psychological response. Syrians desperately seek existential buffers that soothe the relentless fear of death. For many, the Salafi buffer, in helping them “feel good about themselves by portraying their groups as undertaking a righteous mission to obliterate evil,” was particularly alluring.

As Aaron Lund explains: “Fighters are drawn to Salafism not by fine points of doctrine, but because it helps them manifest a Sunni identity in the most radical way possible, while also providing them with a theological explanation for the war against Shia Muslims, a sense of belonging, and spiritual security.” Others speak of Salafism’s capacity for transforming: “The humiliated, the downtrodden, disgruntled young people, the discriminated migrant, or the politically repressed into a chosen sect (al-firqa al-najiya) that immediately gains privileged access to the Truth.”

Claims of marketing gimmicks notwithstanding, by “growing their beards” and observing Salafism’s religious and social code, Syrian rebels transform themselves into “heroes straight out of the Quran.” Thus:

“They no longer need to fear death, since they can be certain of their place in heaven. They no longer need to grapple with self-doubt and moral qualms, since Salafism tells them that they are acting on God’s command. They are no longer embroiled in a confused and dirty war for their family, village, or sect, or for the warlord that pays them — they are fighting a righteous jihad to defend the Muslim Umma.”

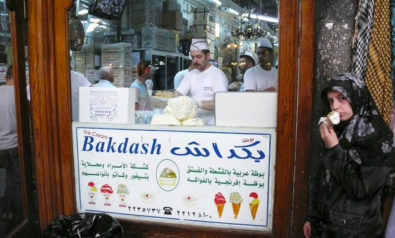

Interestingly, TMT may also explain why Salafism was at first confined to the periphery and slowly metastasized to Syria’s metropolises. Aleppo, long the country’s commercial hub, was (along with Damascus) largely immune from the violence that gripped the outlying cities and villages throughout 2011. One can thereby extrapolate that morality salience —the preponderance of macabre images or cues that induce death anxiety — in these relatively stable areas was less pronounced. However, as they succumbed to turmoil, morality salience became more acute. The outcome, explained an activist in Damascus’ Barzeh neighborhood, was that: “People got more religious, they got closer to death, you could be a martyr so people who drank or went out at night corrected themselves.”

In touting the conflict as a cause in the service of God, one that is part of an epic end-all battle preordained in the Hadith (sayings of the Prophet Muhammad), Salafism better enables the existentially fraught to cope with the unremitting fear of death.

Still inexplicable is why Sufism — long the predominant cultural world-view among Syrian Sunnis — was conceivably an insufficient existential buffer. Tellingly, TMT suggests that people “respond to existential fear by clinging to aspects of their world-views that are best able to provide protection at a given point in time.” Is Sufism simply not up to the task?

“Kumbaya” Just Doesn’t Cut It

Given the war’s trenchant sectarian vein, for many it apparently is not. A priori, the reason likely has to do with both contemporary Sufism’s non-sectarian/pluralistic undertones, and its concomitant co-option by the regime for pacifying the Sunni street.

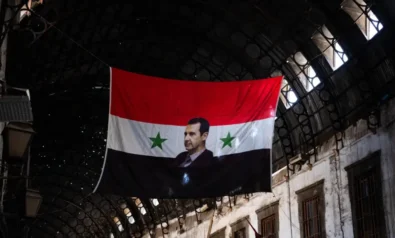

The latter is certainly understandable; Alawites, a historically persecuted minority, have predicated their survival on maintaining the reins of power. Toward that end, the regime employed a strategy of effacing ethnic differences by promoting themes of secular pan-Arabism and confessional ecumenism. Sufism’s motifs of “mutual civility, interaction, and cooperation among believers, regardless of sect,” clearly fit the bill. As one fabled Sufi teacher writes: “The weapons of peace and tranquility will grant us victory no matter what enmity, what hostility threatens us.”

Following the brutal suppression of a Muslim Brotherhood-led insurrection in 1982, regime efforts at playing up these non-confrontational tenets accelerated. A modus vivendi with key Sufi luminaries surfaced, affording them a place in the public sphere — positions at educational and political institutions — so long as they defended or eschewed criticism of the regime, and limited their work to religious, spiritual and moral enlightenment.

On the heels of mass protests and, soon after, the armed uprising, the Sufi establishment — to large measure — kept to its end of the bargain; many chiding the rebellion, airing their support for the regime or remaining neutral in the face of the harsh crackdown.

To be sure, some Sufi movements, the Zeid and Students of Sheikh of al-Sham group specifically, did join the protests and fighting. However, despite representing the largest denominational constituency, “very few activities are carried out in the name” of Sufism. Moreover, the strident legitimization of regime barbarism on the part of some Sufi clerics has disillusioned erstwhile followers, and effectively pushed them into the Salafi fold.

Alas, under the current circumstances of confessional violence, Sunnis find little existential solace in a worldview that, at least contemporarily speaking, is largely non-sectarian. The prodigious role of Shia fighters in quelling the rebellion not only makes it harder to do so, but also has simultaneously propped up Salafism as a headier existential salve.

In touting the conflict as a cause in the service of God, one that is part of an epic end-all battle preordained in the Hadith (sayings of the Prophet Muhammad), Salafism better enables the existentially fraught to cope with the unremitting fear of death.

Abstract vs. Absolute

Tellingly, studies have showed that MS “reduces liking for art that seems to lack clear structure or meaning.” And therefore: “All else being equal, worldviews that offer a clear vision of an orderly meaningful world are likely to be particularly appealing when thoughts of mortality are activated.”

Indeed, Salafism’s literal exegesis of Islamic texts — juxtaposed with the idiosyncratic allegorizations of Sufism — embalms terrifying uncertainty with absolutes. It rewrites the script: The Syrian regime and its Shia protectors are casted as enemies of God, and the rebels his praetorian guard. Falling in battle is no longer a specter; it is a cachet in this world and a luxury suite in the next. Paradoxically, it is through death that one obtains eternal life.

Tested in Time

The implications of this theory are several. First, it sheds an alternative perspective on why the West’s reluctance to allow for the defense of Sunni populaces is partly responsible for the Salafization of the rebel opposition. It suggests that had the West worked to modulate the rise of morality salience — by providing surface-to-air missiles (SAMs) and establishing safe zones — the spread of Salafi evangelism could have been moderated.

Second, this theory underscores the futility of regime efforts to batter the opposition into submission. To the contrary, the more these efforts are redoubled, the more civilians and rebels will find refuge in Manichean world-views. And given the regime’s umbilical dependence on Iranian-sponsored Shia militias for advancing on the battlefield, Salafi Jihadism — which views Shias as “more heretical than Jews and Christians, [and] even more so than many polytheists” — makes for a very compelling narrative.

The continued resonance of such chauvinism will lead to endless cycles of “violence and counter-violence,” and a conflict that will only grow more intractable. Paradoxically, the more Syria — abetted by its allies — pursues an end-all military solution, the less likely a military victory becomes.

Third, there are good reasons to think of Salafism as an evanescent anomaly, one that — as a response to death anxiety — confers utility at the present, but fades as upheaval subsides. Some argue these (Salafi) movements are “primarily a means of war” whose vitality is “intimately connected with the conditions of the current armed struggle and the exceptional ( brutal) circumstances of the Syrian revolution.” While becoming more supportive of “groups that advocate the implementation some form of sharia law,” Syrians and Syrian Islamists alike “do not agree with the radical Salafi jihadist revolutionary agenda and [its] rejection of political Islam.” Thus, Salafism’s hitherto inability to formulate an attractive peacetime agenda means its resonance is largely domiciled in periods of high morality salience (war and political instability).

Moreover, because “the specific situation determines which aspects of people’s cultural worldview and which corresponding norm are salient,” lower morality salience may restore Sufi themes of confessional harmony to the ideological forefront.

The above premise will be tested in time. For now, the West must accept Salafism as a temporary human response and “go with the flow.” In lieu of shunning such affiliated groups, the West should work with them in providing a semblance of normal life for their territorial subjects. If this means dispatching ancillaries for effective governance or even SAMs, so be it. Salafists are a fact on the ground that the US cannot simply wish away. At the end of the day, it is only in peace (when morality salience is low) that Salafism will discredit itself — but we have to get there first.

The West may blanch at the thought of a post-war Islamic state, but it has more to fear from a sustained status quo. The longer mortality is salient, the stronger the Salafi current will become.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment