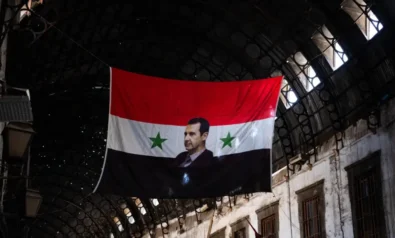

The constant fear of death has transformed Syria’s secular Sunnis into warriors of God.

The prevailing narrative of the Syrian Civil War tells of a conflict that sprouted as a struggle for socioeconomic reform, but soon blossomed into a canonized religious showdown. As it stands, Salafi forces dominate the revolutionary landscape. Ideological differences among them abound, ranging from subtle to irreconcilable, but all purport to be doing God’s bidding: to wit, purging the ruling apostates and enshrining his heavenly rule. Strangely, this evangelical phenomenon is at odds with Syrian Sunnis’ longstanding Sufi mores of pluralism and religious moderation.

Numerous etiologies try to account for this aberration. One contends it is all about material considerations. That is, the rebels are masquerading as Islamists because such is the denomination of those offering to bankroll their struggle. If ideological palatability is an impetus, it is a negligible one. Alternatively, some rebels may have been lured by material factors at first, but ultimately conformed to a Salafi ethos as a process of socialization. Another theory sees that Salafism was brewing well before the revolution due to failed economic policies, and the 2011 uprising was merely its inflection point.

Admittedly, the authenticity of these religious “awakenings” is hard — if not impossible — to define, as the truth is locked away in the human mind. However, what we do know is that the minds of Syrian Sunnis are forever being subjected to the ghastly sight of what now exceeds 150,000 deaths and counting. Accordingly, any theory assaying the motives of this born-again bonanza cannot ignore the psychological implications of this macabre reality. Regrettably, such an angle is virtually absent in the topical discourse.

Twenty years of research in the field of existential-psychology has revealed a mountain of evidence showing that reminders of death — morality salience (MS) — increase one’s “striving for self-protection and efforts to defend or even increase self-esteem.” This author maintains that many Syrian Sunnis pursue the forgoing by adopting the Salafi ideology. Before proceeding with these arguments, some important clarifications are in order.

Clarifications

First, while this author refers to Salafists monolithically, they are not. In fact, the Islamic Front, the Syrian conflict’s Salafi flagship, is a conglomerate of seven factions, which themselves are conglomerates of smaller sub-factions. The fault lines between these camps have been blurred by the exigency of uniting in opposition to the Assad regime. While all desire the emergence of a fundamentalist Islamic state, their philosophies on how to get there are loosely arranged into three main camps:

1) Moderates: Among this cohort is the Believers Participation Movement, led by Sheikh Louay al-Zabi, and other groups that usually abjure the use of violence as a vehicle for change in favor of political activism and dawa (religious advocacy).

2) The traditional and scientific: Leaning toward the philosophy of Mohammed al-Soor, the camp’s principal strategy is grassroots proselytization while abjuring political participation and, generally speaking, violence against heretical Muslim governments. Its standard-bearers are largely the myriad factions, which comprise today’s Islamic Front.

3) Radical jihadists: Those who condemn political participation — which they view as heretical — and believe that an Islamic state or, more broadly, a caliphate must be forcefully imposed. This includes, among others, Jabhat al-Nusra led by Abu Mohammed al-Golani, as well as the infamous Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIS) under the helm of Abu-Bakr al-Baghdadi.

In the 1990s, Syria’s hinterlands, long a bastion of secular Arab nationalism, fell victim to a nosedive in living standards and what was widely perceived as regime favoritism toward the urban bourgeois. To ameliorate the economic malaise — while showcasing its liberal bona fides — the Hafez al-Assad regime allowed Gulf-sponsored Salafi missionary groups space to “organize social and humanitarian activities.”

That said, the term Salafization should be construed as the ideological gravitation of heretofore religious moderates or secularists — whether groups or individuals — to any of the above three camps. The emphasis is, therefore, on their mutual perception of their fight as one against the enemies of god and not their philosophical nuances.

Lastly, this author recognizes that the same psychological dynamic at work among the Sunni opposition is also likely to affect its archrivals. While not disparaging the implications of the latter, the author nonetheless focuses on the former.

Show Me The Money

To reiterate, there is little scholarly consensus over the overriding catalyst of Syria’s Salafi awakening. Some echo “Resource Mobilization Theory” (RMT) and see the ideological orientation of rebel constituencies as determined by the highest bidder. As Aaron Lund put it: “Size, money, and momentum are the things to look for in Syrian insurgent politics—ideology comes fourth, of even that.”

Accordingly, the paucity of Western military support for secular-moderate rebel factions is said to be compelling groups and individuals alike to imbibe Salafism; the persuasion of the opposition’s most enthusiastic benefactors. This assertion is bolstered by anecdotal evidence indicating that: “Low-level recruits to Syria’s ‘Salafi’ factions are really just religiously conservative Sunni men, including many who have turned religious during the war.”

Indeed, though their estimated numbers range from 45,000-60,000 fighters, making it the largest contingent among the rebel opposition, not all are prototypical Salafis “or even ideologically stringent Islamists.” Long beards — an earmark of Islamic piety — are indeed a prominent feature. But such fashion statements are viewed as marketing ploys geared toward “religious donors in Saudi Arabia and the Gulf who want to support Salafists and more conservative elements within the opposition.”

True Believers?

Still, not everyone believes it is all about money. Joshua Landis highlights the public statements of various Salafi militia leaders calling for a post-Assad Islamic state as probative of a genuine political disposition. Further grist is found in the Syrian countryside where Salafi sentiment was strengthened — albeit to a limited degree — well before the 2011 revolution.

In the 1990s, Syria’s hinterlands, long a bastion of secular Arab nationalism, fell victim to a nosedive in living standards and what was widely perceived as regime favoritism toward the urban bourgeois. To ameliorate the economic malaise — while showcasing its liberal bona fides — the Hafez al-Assad regime allowed Gulf-sponsored Salafi missionary groups space to “organize social and humanitarian activities.” It was seemingly a convenient solution; a way of alleviating Syria’s failing state-dominated economy on someone else’s dime. In fact, even ultra-conservative Salafi preachers were permitted to “propagate their message, as long as they confined themselves to mosques and charitable work [and remained apolitical], and abided by the regime’s red lines.”

Hewing the above, the money vs. ideology dichotomy essentially becomes a “chicken or the egg” dilemma: Do recruits acquire their ideological convictions, if at all, only after succumbing to material considerations, or does the former pre-exist irrespectively?

But while religiosity was on the upswing — a trend the regime leveraged for churning out jihadi-insurgents to pin down US soldiers in Iraq — the economic hardship of Syria’s working-class rural Sunnis continued. In 2008, “as part of an under-the-table understanding with the USA, Iraq, and other governments,” the regime pulled the plug on anti-American Salafi jihadists and rolled back their societal inroads. Salafists and former Iraqi fighters were corralled into prison, while the former’s missionary work was curtailed and religious sermons on Fridays were strictly monitored. Perhaps most incendiary, women wearing the niqab (face veil) were banned from teaching in schools. With overt public support and affiliations forced into hibernation, the Salafist activity that remained was unorganized and confined to the periphery.

As such, regime repression has muddled the true extent of Salafism’s pre-war penetration. What we know is that Sufism, a mystical branch of Sunni Islam, has immemorially garnered the widest acceptance among Syrian Sunnis (particularly the merchant, middle-class), while Salafism was all but invisible in the country’s major cities. It is fair to say that pre-war Salafism was, therefore, an aberrant and nascent phenomenon, one whose growth the regime had stunted on one hand, while sowing the seeds for its eventual comeback on another. Still, did these seeds germinate into the powerhouse of today because of money or genuine ideological bewitchment?

A Little Bit Of This, A Little Bit of That

The answer could be a medley of both. For instance, recruits could have initially been lured by material support and yet, after a period of religious indoctrination and assimilation, came to see ideology as a reigning propellant. This hybrid hypothesis is evidenced by the recruitment practices of many Salafi factions who, while conceived around a religious core leadership early on — particularly those released from the infamous Sednaya prison in 2011 — went on to “recruit far and wide among local Sunni Muslims.”

In fact, in many cases, these groups will admit “any aspiring fighter who enjoys a good personal reputation among the locals, and seems to fulfill basic demands of religious commitment.” While stricter than the mass-recruiting practices of most non-Islamist factions, such protocol pales in comparison to the gradational vetting process of al-Qaeda-affiliated Jabhat al-Nusra, which puts its recruits under rigorous ideological scrutiny.

Hewing the above, the money vs. ideology dichotomy essentially becomes a “chicken or the egg” dilemma: Do recruits acquire their ideological convictions, if at all, only after succumbing to material considerations, or does the former pre-exist irrespectively?

Perhaps the two exist in tandem; that is, one can be both ideologically and materially lured, each to equal or varying degrees. For example, many of those who defected from the secular-nationalist Free Syrian Army to the Salafi-jihadist Jabhat al-Nusra point to its “Islamic doctrine, sincerity, good funding, and advanced weapons” as cardinal inducements.

How such preferences are weighted remains the overarching dispute. Nonetheless, over-emphasizing material incentives is problematic, insofar that it ignores the psychological dimensions of prolonged exposures to death.

*[Read the final part here.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment