Duolingo’s push to “translate the web” is not as straightforward as it seems.

Luis von Ahn, creator of the reCAPTCHA verification system that helps digitalize books, has set out to “translate the web into every major language.” In this TED talk, he reminds us the Internet is fragmented into multiple languages and that the biggest portion is in English. “If you don’t speak English,” he points out, “you can’t access it.”

In order to make the web accessible to a wider range of linguistic groups, von Ahn and his research team created Duolingo: a free language-learning app. Once Duolingo students have reached an advanced level of the language they are studying, the app feeds them text to translate. The Duolingo team then compiles the translations and uses an algorithm to come up with a final version, which companies buy for a below-market rate.

Students learn by translating real world texts, as opposed to sentences written for language instruction; companies that contract with Duolingo get cheap translations; and Duolingo remains free.

As a business model, the agreement is highly effective, but Duolingo’s other claims — that their translations are of professional quality and they are making the web more democratic — are highly questionable

Quality Control

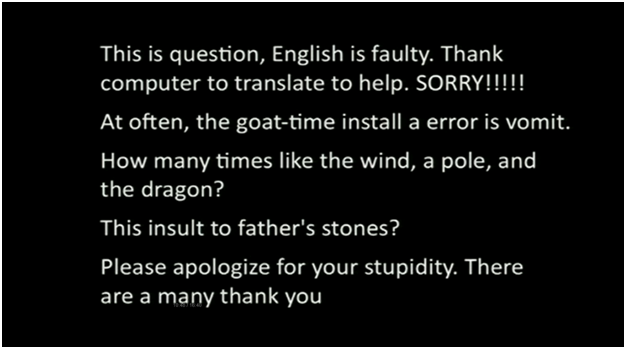

Von Ahn correctly notes that while machine translation has evolved significantly, services like Google Translate are notoriously (and sometimes humorously) unreliable. The Duolingo creator uses this series of humorous examples of comments translated from Japanese to English to highlight the problems with machine translations:

Both Google Translate and Duolingo compile large amounts of data and use algorithms to determine the final translated version of a text. However, whereas Google “looks for patterns“ in documents already available online, Duolingo feeds text in its original language to translate.

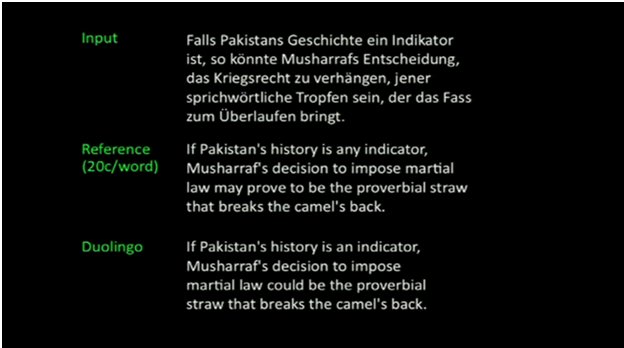

According to von Ahn, this method is better because the translations are not simply machine-driven — they are crowd-sourced. To vouch for the quality of Duolingo’s translations, von Ahn gives an example of a text translated from German, favorably comparing Duolingo’s translation with that of a professional translator:

The translation reads eloquently, but that does not mean Duolingo is consistently reliable. Google Translate also works well if it is drawing on high-quality content. As Esther Allen explains in her book, In Translation: Translators on Their Work and What it Means, if you put the first line of García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude into Google Translate, you will get a solid translation because Gregory Rabassa’s professional translation of the famous book has been cited many times online and Google is drawing on that data.

But this does not mean Google Translate is reliable. It just means that, in some cases, translations (by humans) are readily available online and Google reproduces them.

We do not have access to the data Duolingo was compiling to produce this translation from German, but it is doubtful that the translations the app produces will be consistently this stellar. Not only are language students not professional translators, students often tend to make the same mistakes.

To give an example, last semester I taught a course on Spanish-English translation. Although my students were all advanced learners of Spanish, many of them made exactly the same errors. For example, when they translated the last paragraph of Jorge Luis Borges’ short story, La busca de Averroes, almost all of my students translated “referí el caso” incorrectly. If I had compiled their translations, I would have ended up with an English version that read, “I referred to the case,” when a correct translation would have been something like, “I told the story.”

Duolingo does have some amount of quality control, but even if the proofreader is particularly attentive and the students happen to be skilled translators, a number of other obstacles complicate their model for translation. First, as Richard Christian points out, good translators do not work by translating sentences in isolation. Rather, they think about the overall context, tone and readership.

Let’s take, for example, the first phrase (in Portuguese) from this article in Brazil’s O Globo: “A questão dos rolezinhos não deixa de suscitar indagações.” Google translates this as: “The issue of rolezinhos not fail to raise questions.” If Duolingo translated this fragment, the English version would likely resolve the grammatical errors because the app relies on human translators.

However, without the context of the entire article, how would a Duolingo student explain what a rolezinho is? They might translate it as “little strolls” as The New York Times did or as “gatherings organised via social networks” as the The Economist did, or choose another word completely.

Either way, even the most talented translators would have no way of knowing which choice is best unless they were able to read the entire article, do some research, and know a little bit about their target audience. Because Duolingo’s method dismisses the complexity of translation, it devalues the work of professional translators, who often do extensive research in order to translate cultural and historical references.

An Uneven Flow

Making the web accessible to a broader range of linguistic groups is certainly a lofty goal and Duolingo deserves credit for making a start. However, details of their business model are more problematic than they seem.

In order to remain free for language learners, Duolingo must profit from their translations. The companies who can afford to pay to translate their content on a large-scale — and, therefore, sustain Duolingo — are profitable entities that already have a strong online presence. They are usually from the English-speaking world.

So far, the two largest companies that have contracted with Duolingo are CNN and BuzzFeed — the rapidly growing host site for viral content on the Internet famous for pieces like these: “37 Pictures That Prove Cats Have a Heart of Gold.”

So far, Duolingo translates primarily from English into foreign languages, and not vice versa. By contracting with BuzzFeed, CNN and other American companies interested in aggressively expanding their audience, the app is reinforcing what Lawrence Venuti, in The Translator’s Invisibility, describes as a “trade imbalance” in the movement of translated material. That is, the US tends to export a great number of texts and import very few and this, according to Venuti, contributes to Anglo cultures being “imperialistic abroad and xenophobic at home.”

Rather than making the Internet more egalitarian, the exportation of texts and video to other linguistic groups reinforces the reign of US culture, while the English-speaking world continues to import very little from foreign cultures. Because its model is essentially capitalist, Duolingo reinforces this dynamic instead of challenging it.

Because the market demands it, Duolingo is often contracted to translate pieces with strong cultural bias (and a non-critical view of American culture). For example, their team of student translators recently completed this Spanish translation of “25 Things That Happen When You’re 25.” The piece received over 15,000 “likes” in Spanish, so BuzzFeed is clearly expanding its audience. Some of the material in the translation is left in English, and the cultural references include clips of comedian Amy Poehler and scenes from Family Guy, The Simpsons, and Friends.

Very few pieces in Duolingo’s list of material currently being translated strive for any sort of objectivity or critical thinking. Even the content listed in the “News & Politics” section tends to include articles like, “Hollywood’s Moneymakers: The Top Paid Stars of 2013,” decidedly unenlightening sorts of pieces that affirm American cultural (and perhaps economic) hegemony.

Duolingo’s stated mission is to build “a world with free education and no language barriers.” They do succeed in providing a free platform for learning foreign languages and this aspect of the app certainly promotes healthy cross-cultural understanding.

However, it is worth taking a closer look at the direction in which that understanding is being developed, while it is important to think critically about what happens when translation is perceived as a simple mechanical activity with no ideological implications.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Image: Copyright © Shutterstock. All Rights Reserved

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment